Wednesday, July 4th, Port Hardy to Fury Cove. We moved up to Port Hardy from Port McNeill on the 3rd, hoping to spend the least amount of time in Port Hardy before kicking off around Cape Caution. Kap checked out a weather window that indicated our best conditions were for the next day. We quickly picked up a few last provisions, and at a local Ace Hardware Kap snagged a couple of items she still needed for fishing (a baby bassinet for stowing fish in the dinghy when they were brought aboard).

One big treat of our short overnight stay in Port Hardy – we met up with Bob Gladics, our old gliding friend from Sun Valley who (along with a friend) had trailered his boat up for a weeklong fishing trip. Kap had run into Bob the previous day at Port McNeill while haunting the local boat chandlery – she heard his voice, and it’s unmistakable. Late in the afternoon, Bob dropped by our dock with most of a salmon he’d just caught and gave us the fillets from it. He then spent an hour (or more) giving Kap a bunch of fishing tips – his version of how to set up the tackle for best effect. It was really good to see Bob, as we haven’t caught up with him for several years now.

Don’t forget – you can click on any photo in the post to enlarge it.

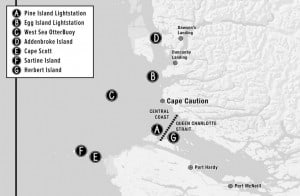

With seven reporting stations you'd think the decision on weather would be an easy one. The problems, though, are manifold. Some of these stations are automated, and "Not Available" is a common statement for a station. The information might be six hours old, and a lot can change in that time. For marine traffic that moves at 8-20 knots speed, with distances from pint G to D of at least 50 miles, the time that a boat is making a crossing is essentially a full day. The "data" in the forecast is mostly wave heights and wind speed and direction, and how that translates into what all of this feels like on your boat is vastly different from boat to boat - and boater to boater.

Next morning we set off from our Port Hardy moorage at 8:30AM (July 4th). There was a bit of fog in the harbor, but we hoped it would blow away once we got into open water, or would burn off when the sun was high enough. Neither happened, and we spent the entire four hour open water part of the crossing in dense fog that never even got to one-quarter mile visibility. Except for the shore outline on our navigation charts and radar screen, we didn’t see anything of Cape Caution, not to mention any other shoreline along the way. And though we met multiple boats, two as close as a quarter mile, we didn’t see a single boat the entire time of the crossing. More disconcerting, we thought our AIS transmitter was working (that would show us up as an AIS “target” on other boat’s navigation systems that were receiving AIS signals), only to find out late in the afternoon that our AIS box wasn’t transmitting. It was unsettling, as two of the boats we met were within a quarter mile – and apparently weren’t watching their radar – as they only knew about us approaching and passing by them because we saw then and called them on the VHF radio. We’re pretty sure there are a lot of boat drivers who figure the areas we’re cruising in are so vast that there’s just no way they can run into anything and just nod off to sleep at the wheel.

Cruising in fog bears a bit of description. The typical fog this time of year is pretty dense, and it’s often only 1/8th mile visibility – which is only 660′ if you want to split hairs. Now, two football fields seems like a pretty good distance to see other boats, land, or rocks, but when the fog is surrounding you 360° and a boat may be heading straight for you from any direction, it’s unnerving as hell. We tend to stick to our normal cruising speed in fog, which is 8-9 knots, and if some other boat is coming head on at the same speed, you have a closing speed of about 20 knots. That doesn’t seem like much, but objects in fog aren’t well defined when you first see them, plus reaction time isn’t instantaneous, and that means a collision could be imminent. We’ve had idiot drivers of small fishing boats running at 25-30 knots, and there’s no way they can be looking at radar, and if you’re on a collision course there’s no way you’ll not collide. For us, the only recourse is to stay glued to the radar screen. Our rule is, Kap does the driving in fog (because she has really good reaction timing and instincts), and I’m pretty good at watching the radar screen.

As soon as either of us spots a “target” anywhere on the screen, we first determine how far away from us it is, how fast it seems to be traveling, and which way its going. If it’s heading anywhere towards us, we put something called an EBL on it (stands for Electronic Bearing Line) – this is a screen gizmo that our radar software has. It’s really quite simple – it’s a line on the screen that extends from our boat marker out to the target. As we move – and the target moves – we watch how the target relates to the EBL. If it’s “coming right down” the EBL, it’s on a collision course with us; if it falls behind the EBL line, it will pass behind us; if it moves ahead of the EBL line, it will pass ahead of us. Essentially, an EBL is nothing more than an electronic screen facility that functions the same as watching a moving object out of your car window – to see how it’s moving in relation to you. It’s just that the radar EBL is more precise.

All in all, cruising in fog is demanding and tiring. There’s nothing fun about it, and it doesn’t take long before you wish you’d stayed back at the dock or anchorage for the day. The trouble is, weather systems that have fog components can last for days on end, and in August – which everyone calls Fogust around here – you could stay put for the entire month if you stick to a rule that you never cruise in fog. The trick to it is to be extremely careful, very vigilant, and don’t take any extra chances.

Once beyond Cape Caution you’re in the B.C. Central Coast region, and everything is much more remote. There are no towns anywhere nearby, and within fifty miles there are only two tiny links to civilization – Dawson’s Landing near the top of Darby Inlet where it meets Rivers Inlet, and the Hakai Research Institute halfway up Calvert Island. Neither has a population over about 25, and in an emergency the only fast way out is by float plane. In fact, as we passed the entrance to Darby Inlet we heard a radio transmission from a cruiser headed towards Dawson’s Landing telling them to expect the cruiser in soon, and that it was meeting a float plane to transport out a passenger who needed medical attention. There are at least a dozen fishing camps dotting the myriad bays and coves, and some of them (like Duncanby Lodge at the entrance to Rivers Inlet), are very high end, catering to “guests” who fly in for weeklong fishing retreats during the salmon runs.

If you want to see where we are now, or better yet, monitor our route progress as we cruise along, you can go to www.ronf-flyingcolours.com and click on the Current Location link in the upper right corner of the home page.

Also, this post is more readable in the online version, plus you can read any of the posts back to 2010 from the archive – just click on the link above to the blog.

Port Hardy – to the south where we came from – and Bella Bella/Shearwater to the north are the only towns within 100 miles, and their populations are in the low three digits. But then, that’s the reason we’re here – to escape the crowds of urbanites – and the increasingly high numbers of cruising boats – that now come as far north as The Broughton’s.

This photo was taken in 2017 when we anchored in Fury Cove for several nights. The biggest of the six (or so) midden beaches inside the cove can be seen at about mid-tide. At high tide the beach is almost completely submerged. The midden extends further to the left about 100 yards. Outside the cove is Fitz Hugh Sound, a huge channel at the north end of Queen Charlotte Sound, forming a 20 mile section of the Inside Passage. It’s protected from the Pacific Ocean by Calvert Island that you can see in the distance. The small white spec is a BC Ferry, the Northern Expedition – a huge car and passenger ferry – that makes a frequent run from Port Hardy to Prince Rupert.

Early afternoon we arrived at our destination for the next couple of night – Fury Cove. As we motored through the tight neck of the cove we could see there were only three other boats at anchor – and with the half-dozen sandy-looking beaches scattered around its perimeter, you’d almost call it a tropical island paradise. What looks like beautiful coral sand, though, is actually broken-up seashells that have accumulated, sometimes over thousands of years, at locations where First Nations people gathered or lived along the shores. These beaches are called middens, and in British Columbia they are protected . . . in the sense that a permit is required to alter the site in any way if there is evidence of human use prior to 1846. The main beach where we take Jamie three times a day has an astonishing number of shells – and it’s hard to imagine how many crab, shrimp, mussels, and oysters were eaten to create that beach.

When we arrived there were only four boats at anchor, and we thought we might have the cove almost to ourselves – and lots of good options on where to drop the anchor. Throughout the afternoon, boat after boat arrived, and by nightfall there were 24 boats around us. Flying Colours is the second boat from left. There was still room for at least a dozen more boats to anchor in the cove, and if it got to the point of stern tying on the shorline, the limit would easily be 10 times that number.

It didn’t take long to suss out the best anchorage – where we could most easily get Jamie to shore for her 2-3 times a day visit. By now the fog had lifted, there was a clear blue sky, warm, and a wonderful day to be at anchor. Throughout the day more and more boats came into the anchorage, and by nightfall there were 24 boats at anchor (and there was room for at least a dozen more without crowding it.

We have a 30" canvas extension for our dinghy deck, giving us a bit more protection from sun and rain in the cockpit. Because it's soft to lay on, Jamie loves to lay here for long periods, particularly when we're away from the boat - watching for us to return.

It was now three weeks since leaving Anacortes, and this was our first night at anchor – not a good idea in territory this remote, and relying on an anchor windlass that had failed us last season. When we dropped the anchor the windlass worked flawlessly. Our real concern arose as we got ready for bed that night – the Maretron monitoring system had a bunch of very screwy readings for our DC house bank batteries, showing that our batteries were dropping voltage much more quickly than normal. We visually monitored the readings for an hour or so, and quickly realized that our batteries would last half the night at most, and we’d then have to start the generator to re-charge the batteries to get us through the night. Something was amiss!

Damn! It’s been less than three years since these batteries were replaced (at an exorbitant cost of about $12,000), and they shouldn’t be failing this early. We had one very major power outage while Flying Colours was on the hard for repairs over the winter, and maybe that total drain of the batteries shortened their life – or maybe it wasn’t the only power outage that we had (but didn’t know about). Whatever it was, we knew we had serious battery problems – and no easy way to fix it.

Friday, July 6th, Fury Cove to Shearwater Marina. We spent two nights at Fury Cove, nursing our battery situation and making a hard decision about what to do next. One option was to go south – but that likely meant going all the way south to Sidney, and doing that would likely mean going home for the summer. The second option – the one we finally chose – was to continue heading north, bypassing our planned stops at the Hakai Research Institute (where we had some great walks last year with Jamie on the sandy Pacific Ocean beach) and skipping a prawn stop at Codville Lagoon that we were really looking forward to. Instead, we’d continue further north to Shearwater Marina, where they have a major shipyard and repair station that was left over from a WWII flying boat base.

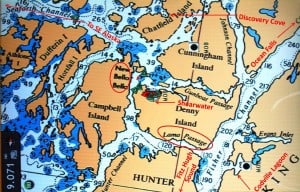

The route from Fury Cove to Shearwater is up Fitz Hugh Sound, which turns into Fisher Chanel as it narrows at the top. Then a left turn into Lama Passage for a 10-mile cruise west then north, passing New Bella Bella at the end, and then a right turn into Shearwater. In 2017, after spending several nights at anchor off Shearwater, we headed up Gunboat Passage (great name for a passage – makes you wonder what the history is – and after a few miles further up Fisher Channel there’s a long channel that leads to Ocean Falls. This year, we spent several days at anchor in Discovery Cove waiting for our batteries to arrive. After they were installed we then went west out Seaforth Channel, where it dumps into the open Pacific for a few miles, and then you duck back into the Inside Passage on the long run to SE Alaska.)

Using our satellite phone I made several calls to Shearwater to organize moorage space for us, either on the marina dock or the shipyard dock and confirmed that an electrical person could look at our problem as soon as we got there. At 7:30AM we pulled up our anchor, threaded our way out to the east side of Fitz Hugh Sound and began our all-day trek north. The day was pretty clear, but with some ground haze – and it was only with radar and some serious sighting with our strongest that Kap spied a tug and tow six miles ahead of us going our direction. With a speed difference of just a knot, it took us the next 40 miles to the turn-off to Bella Bella and Shearwater before we’d overtake it.

Moorage at Shearwater is on a simple T-dock. Flying Colours is on the inside of the top bar of the T – in the upper center in this photo. The photo was taken just after we arrived, and before the Bolero rafted up to us. The two aluminum boats in the foreground – at the bottom of the shore ramp – are Seabus’ that run hourly from Shearwater to Bella Bella – a 20 minute trip each way. The dock on the right is for commercial fishing boats, and just before an “open” day for fishing, the dock has boats rafted seven deep. Given how difficult it is to get moorage, this marina could stand some major dock expansion.

On arrival at Shearwater we were given immediate clearance for a great moorage spot on the marina dock – unlike last year when we waited three days at anchor and never did get on the dock. Once secured, Kap did her engine checks and got the engine room ready for an electrician/mechanic to come aboard. I headed to the marina general office to let them know we’d arrived. They wrote out an open-ended Work Order that listed “house bank battery check” as the top priority, with “other items as needed” listed just in case. My sense told me this wasn’t going to be an inexpensive repair stop.

Within an hour, a youngish guy named Nate came aboard – and we were happy to see that he really seemed to know his stuff. But then after a bit we weren’t so sure . . . when most of what he said contradicted what Mike Radding had told us in an earlier satellite call. Very emphatically, Nate diagnosed our problem as not being with the batteries at all, but rather, with our Maretron monitoring equipment that he said wasn’t reading the battery voltage correctly. After fiddling with our on-screen Maretron settings for a bit he suggested we run some power draining exercises while he went off to work on a half dozen other boats that were also in line for his services.

On his return a couple of hours later, and after hearing the results of our battery drain exercise, Nate did a more thorough test of the batteries. This time he diagnosed our 8-battery house bank as having two batteries with shorted out internal cells. After a lot of discussion we made a preliminary decision to replace just the two failed batteries.

It was now late on Friday afternoon and the parts and service desk at the yard was closed for the weekend. There was nothing to do but wait out the weekend. First thing Monday morning we’d have a chat with the parts guy, Zach, to get two replacement batteries ordered up from Vancouver. Little did we know just how long this equipment delay would be – or what the effect of the current (and stupid) tariff war between the U.S. and Canada.

The big question was, were we doing the right thing? Everyone advises to never (ever!) replace just one or two batteries in the bank, as it will cause all of the other batteries to fail. But in this case, what choice did we have? These batteries, American made but sourced in Canada and as remote as we were, were going to cost us almost $1,000 each – whereas they cost around $400 each in the U.S., so replacing the whole battery bank made no economic sense at all. A call to Mike Radding (our trusted Fleming service guy in Newport Beach (CA) confirmed that our logic was sound, and that convinced us.

While all this was going on, Christophe (the marina Harbourmaster) stopped by to tell us we’d have to let another boat “raft up” to our starboard side. We’re never fond of rafting, because it means another boat is tied up to our side, risking some cosmetic damage, plus you lose all of your privacy inside your own boat (and they lose theirs too), and the only way for the people on the other boat to get to the dock is through our cockpit or swim step. This time it worked out quite well, as the couple on board Boléro, a 48’ Kady Krogen were from Seattle, very nice, and having them scamper across our boat wasn’t a problem at all. They too had boat problems – an alternator that needed replacing, and it arrived on the supply flight that came in soon after they tied up to us. Everything on a boat is always difficult to replace/fix, so they were next to us for the weekend.

At left is the Sinbad, the 135’ hulking yacht owned by Joe Diamond of Seattle – and you can see how this behemoth towers over us. They have a full-time crew of at least three on the boat, with one friend aboard. It definitely gives one an idea of conspicuous consumption. Rafted up to us on the outside are our newfound friends from Seattle on Boléro. At our stern – sailboat Dawn Flight – has been on a multi-year around the world cruise with the couple who live aboard – and they are working the summer at Shearwater, the fella assisting Christophe on the dock, and his wife clerking in the grocery store. It’s not a bad way to work your way around the world. They plan to winter in Mexico, then through the Panama Canal, and up the East Coast to their home in Toronto.

Making matters worse, the sun, stars, and moon were blotted out the next day by the arrival of Sinbad, a behemoth yacht owned by Joe Diamond and his wife. Every paid parking lot in Seattle is a Diamond lot, so every dollar you plug into his collection boxes goes into his pocket, and that’s how one pays for a 135’ example of conspicuous consumption. To our chagrin, the Sinbad was moored directly across the 8’ wide dock from us, towering over us, and as a result we couldn’t see the sun each day until after noon. If there’s one thing we don’t like when we’re cruising, it’s these damn big ostentatious yachts, which is interesting, as every non-boater who spots something like the Sinbad has to stroll by to catch a closer glimpse and ooh and aah over it. (We overheard one couple passing by, “Oh, it’s just like a cruise ship! Isn’t it fantastic!”)

First thing Monday morning we headed for Zach’s parts counter, and after futzing with him for an hour over which batteries to order, he (hopefully) got the right ones ordered – but the earliest he could have them in was next Monday, seven days from now. While waiting for him to get the order placed, I searched the internet to see if Prince Rupert might be a better bet after all, and found that while it’s a much bigger town, it has even fewer marine services than Shearwater.

Nate and Christophe had the pleasurable task of lugging the two failed house bank batteries off the boat. These hummers weigh in at 107 lbs, so they’re nothing to sniff at, particularly if you’re a 97 lb weakling. Our battery bank was up-sized when we ordered Flying Colours, with the taller (by 3”) AGMs that boost the amp hour charge. Our moorage on the dock was about 400’ from shore, so Christophe had brought out a rickety wheelbarrow-style dock cart to take them ashore, and it was all he could do to push it down the dock.

Batteries such as the big golf cart high energy AGMs that we use can’t be air freighted from Vancouver – they’re deemed hazardous cargo – so they’d be shipped up on the weekly supply barge. That meant they wouldn’t arrive at Shearwater until late next Sunday night – a week from now! The barge would be unloaded on Monday, and the work to replace our batteries couldn’t start until Tuesday. We were now resigned for it to be at least a further week and a half delay before we could be on our way.

With time on our hands over the weekend, Kap finished up the electronics control board replacement for our WhisperGen – which has now been out of commission for two cruising summers. The replacement board had arrived last September from New Zealand, but with Flying Colours in the repair yard all winter nothing could be done. Getting this back in running condition was now a top priority for keeping our house bank batteries topped up – and give us more hours of battery power at anchor. After the installation was complete, we ran test after test but now the unit had a new error code and no matter what we tried it wouldn’t run. We even added on to our Shearwater Marine Work Order and had a mechanic down for a couple of hours to see if he could figure out the problem. No go. We’ve now written to the New Zealand guy who is the only person left from the factory disaster after the 2010 earthquake in Christchurch, telling him that we’re either going to swap the WhisperGen out this fall for another type of unit (which we aren’t wild about), or maybe we need to have a discussion about paying him to come over this fall to get it working for us.

Christophe was now checking with us every day on our work order progress, because he had far more requests for dock space than he had dock availability. As long as we had our Work Order open, we were OK to stay and we took good advantage of it. To help our cause, we fed Christophe stories about battery tests that Nate wanted us to run (only partially false – they all had elements of truth to them). Everyone we worked with was too busy to talk with others around the marina/shipyard, so our stories weren’t questioned. Nevertheless, we had the inevitable chat with Christophe about “going someplace else” to wait out the arrival of the batteries. Someone else obviously needed the dock space more than us, and just waiting around wasn’t a valid task on the Work Order.

Besides our upcoming batter shipment, the weekly supply barge carries a couple of refrigerated semi-trailers, stopping first at Bella Bella and then Shearwater, with huge pallets of groceries for the stores at each place. While restocking on Monday mornings, the small grocery at Shearwater doesn’t open until 1PM, so we caught the Seabus across to Bella Bella to do our grocery shopping, If we had to wait out a week, we weren’t going to do it at the dock here in Shearwater, and we’d need supplies to be out somewhere secluded. The Seabus trip across is 20 minutes – free for First Nations people and guests of the Shearwater fishing lodge; C$5 one way for cruisers like us parked at the dock or anchored in the harbor.

When we stopped at Shearwater last year I needed to have a nasty deer fly bite near my eye looked at by a doctor – there was a fear that it would spread an infection to my eye – and there’s a very nice (but small) medical clinic in “new” Bella Bella. When I got off the Seabus that brought me from Shearwater, I walked a block up from the ferry dock – and ahead of me was a burned-out hulk of a building that once held the Waglisla Band Store, but had burned down just a few weeks earlier. A temporary grocery was open across the street – but now the replacement was finished and it’s probably the nicest little grocery in a small village up and down the coast.

Bella Bella is an interesting First Nations village, part of the Waglisla Band (a band is equivalent to a tribe). At first glance you might think it’s a dreary village, but it has a lot more going for it than you get from that first impression. It has a long history on this coast – dating to long before its original location moved from Denny Island (where Shearwater Marina is located) to Campbell Island.)

The new long house under construction in the tiny downtown of Bella Bella. When complete, this will likely be a huge cultural benefit, not to mention an incredible sense of pride for all band members in the village.

In preparation for departure we made additional forays to Bella Bella for provisions that we’d need. The grocery at Bella Bella is about four times the size of the little store at Shearwater Marina, so it’s worth the trip.

On one trip we walked up a block from the grocery store for a close look at the new First Nations long house under construction. In the accompanying photo, note how large the vertical framing columns are that Kap is standing next to – each is 1-piece from a huge cedar tree. And note that the roof is a lattice of full-length cedar logs. The hole in the center of the roof is where a large chimney will let smoke escape from a huge fire pit that will probably be in the center of a large ceremonial hall where traditional dances and other ceremonies will be held. The band most likely has control over a nearby forest area (and not giving up their logging rights), and it probably still has a bunch of old growth cedar in it.

I don’t know the details of it, but this appears to be the current tribal ceremonial house. While it’s very nicely done, note how small it is compared to the new one being built.

With a bit of conniving we managed to delay Christophe’s eviction notice until Wednesday, by adding to our Work Order and then telling him about additional tests that Nate wanted us to do.

As usual, we’ve been met or passed by the Alaska Marine Highway System Ferry, the Kennecott, several times while cruising here. It’s home base is Bellingham (WA), and provides a car/passenger ferry service to SE Alaska via the Inside Passage. It’s a fast ferry, cruising at around 20 MPH, and carrying up to 750 passengers and 80 vehicles. It's a popular run, and is often sold out.

(We don’t think Christophe had an aversion to this conniving, as he was subtly milking the whole process for large tips when it came time for moorage payment. One of his tactics seems to be currying favor with owners in situations such as ours, and it probably leads to larger tips than he’d otherwise get. We’d already been warned about this from a couple of other cruisers, but didn’t know how he was pulling it off. When it came time to check out and pay for our moorage I saw firsthand a bit about what was going on. Throughout our entire cruising region there isn’t a single marina that has a line for “Tips” on the credit card receipt that you sign (like a restaurant charge does) – except for Shearwater Marina. As I was signing our credit charge I specifically asked Christophe if the tips went specifically to him, and he emphatically replied, “You bet they do!” Having announced that, he then said he was giving us a 50% moorage discount for all five nights for having someone rafted to us, even though Bolero was alongside for just three of those nights – essentially bilking his employer with that discount so that I’d have an incentive to give him a bigger tip. As far as I’m concerned, the guy’s a real snake.)

Close to the shore, tall mountains provide protection on two sides from the wind at Discovery Cove. This incredibly calm scene was taken early in the morning, before the water was disturbed, and it's a picture postcard of our new-found friends, Rick and Lynn Parnell of La Conner on their trawler, Spring Tide.

Another picture postcard. While we were at Discovery Cove, another Fleming – this one a 65’ model called Balladeer from Vancouver – came in and anchored in another small bay inside the cove.

Wednesday, July 11th, Shearwater Marina to Discovery Cove. To wait out our forced time, we decided to head for Discovery Cove for a few days, a secluded little bay just 8 miles NW of Shearwater – close enough that we could quickly get back for installation of our batteries when they arrived. We’d also heard it is one of the most picturesque anchorages in the area. It didn’t disappoint us – but the ravaging deer flies did (they basically kept us from spending any time in the cockpit enjoying the scenery or having a Happy Hour on the deck).

At the head of the small bay where we anchored, the tidal flat was very gently sloping, so that at low tide the drying area was extensive. Years ago – no telling when – the First Nations who lived – or visited – this cove dug out four weirs that trapped fish in the manmade ponds as the tide was going out. In this photo at high tide, the water is deep enough that you could easily take a dinghy all the way to the head of the bay - and in this photo Kap is taking Jamie ashore with the kayak..

This second photo, of the exact same scene a few hours later at low tide, shows three of the step-down weirs – the fourth is out of sight, further up a channel that runs down from a lake that’s just around the corner. The unsuspecting fish didn’t have a clue what their fate would be on the falling tide.

We made some new cruising friends at Discovery Cove – Rick and Lynn Perry aboard their 48’ trawler named Spring Tide, who hail from La Conner, just a few miles south of Anacortes. We anchored near to them in one of the three small bays of the cove. The weather forecast was for a bit of a blow from the NW (an understatement), and this spot gave us excellent protection from the winds. Our neighbors ventured out each day to the main channel to do some fishing and prawning (they were completely skunked the whole time), and they reported back that the winds were whipping up at 30 knots, and buffeting them with 3’ seas, yet it was totally calm and smooth water at our anchorage. Except for the dear flies that were devouring us, we couldn’t have asked for a better place to hide from the weather.

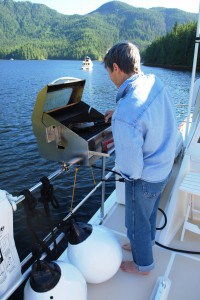

Kap is doing her duty at Discovery Cove. We learned this rule from Paula and Jim on Apt. 5 – the ship’s captain is also the BBQ chef. Kap takes it seriously, and about half of the meals we have on Flying Colours are from Kap’s BBQ. Our BBQ is a very good Australian model that we bought for Cosmo Place in our first year of cruising. It’s rail-mounted on the dinghy deck, with two propane tanks that were specially mounted under the seats in the fly bridge driving station, and hoses are brought out to connect up the gas each time.

Sunday, July 15th, Discovery Cove to Shearwater Marina. On our last day at Discovery Cove we had a leisurely morning, as it was just an hour’s cruise back to Shearwater. After our first morning latte, we put the PFD on Jamie, loaded her up in the dinghy, and set off to visit our usual spot ashore for her morning bidness. The tide was going out and the deer flies were trying to eat me alive, so after Kap got out, and before carrying Jamie to dry ground, she gave me a push off to back out and idle around in deeper water. At the current tide level, the approach to shore was very shallow, and the keel was already a bit stuck, so I lowered the outboard prop just a bit into the water – enough to hopefully give me some backward propulsion but not touch the gravel and muck on the bottom. As I gave it some gas I looked back and could see it was churning up dirt and tiny stones – and I still wasn’t going anywhere. I gave it a bit more gas and it finally backed off, but instantly an alarm started going off somewhere in the steering column. In all the hours we’ve used this dinghy I’ve never heard this alarm before, but it didn’t sound good. A moment later plumes of water vapor poured out the back of the motor. I lowered the motor all the way into the water, then circled around to see if I could figure out what was going on. I was loathe to shut the motor down for fear of if it not starting again. The moment I saw Kap and Jamie returning to the beach I maneuvered in and picked them up. The alarm continued and so did the water vapor (Kap was adamant it was smoke, and I couldn’t convince her that smoke doesn’t dissipate that quickly).

I pointed the nose towards Flying Colours, and as fast as I dared run the motor we returned the three-quarter miles to safety. I immediately shut the engine down and the alarm stopped. Kap raised the cover on the motor, checked the oil – it was OK . After a discussion about what the problem could be – and finally noticing that the normal jet of coolant water wasn’t squirting out the back of the motor – we deduced that the motor may have sucked up dirt or a bit of gravel into the intake for the raw coolant water line for the motor. Kap hooked up our fresh water garden hose to the flush coupling – thinking that maybe this would unstick whatever was in the intake. It definitely squirted the water back out, but didn’t solve the problem. Running out of ideas, we decided the best thing was to add it to our Work Order when we returned to Shearwater. We had to be there that morning for the battery installation, so maybe we could find a mechanic who knows something about outboard motors and have him fix whatever the problem was.

At Shearwater we got an even better spot on the dock, just 25 yards from the ramp up to shore (for an easy walk with Jamie). I immediately headed for Zach’s parts counter and he confirmed that the batteries had arrived on the barge. But with everything else from the barge having to be unloaded and checked in it would be late afternoon before he could release the batteries to Nate, and ready for installation on Tuesday. I raced upstairs to have Erica (by now I was on first-name basis with many of the service staff) add the dinghy to the Work Order. She told me our mechanic for it would be Jay, and suggested I track him down outside of the big WWII hangar where he does his mechanic work. I did as Erica directed and tracked Jay down. He told me he was finishing up another job at the moment, but if I brought the dinghy over to the haul-out dock he could look into the problem. After putting it in the water I nursed it over to the haul-out dock.

Kap also wanted to have the guest head looked at (which serves as our day head), as it had developed an intermittent problem that was quite troubling. It would flush just fine several times, then unexpectedly you’d press the button to flush and nothing would happen. And it didn’t make sense to do a test flush ahead of time, as it might work then, but not work right after that. Besides, that wastes all the water of a flush, and that’s not a good thing. Knowing that we needed “ammunition” on the Work Order to stay on the dock for a few days, I also added the guest head problem to the list.

A couple hours later Jay showed up with the dinghy, saying it was all fixed. The problem was the cooling system’s thermostat – all gunked up and stuck shut – which was a common problem with cars from the 50s that I grew up with, but I hadn’t thought about something like that for years.

First thing Tuesday morning Nate showed up with the batteries, and almost before we knew it he popped his head up and said they were installed. He readjusted the Maretron settings to reflect our full complement of house bank batteries, and declared us good to go. Having him captive, Kap took the opportunity to ask if he could take a look at the guest head problem.

Prior to this I had called Headhunter, the toilet manufacturer in Ft. Lauderdale (FL) and got a service technician who initially seemed very helpful. Trouble was, after sending us a detailed diagram of the solenoid that activates the “jet” flush for our model, we couldn’t locate any such thing (I should say, Kap, as like all other mechanical/electronic stuff on the boat, she was honchoing the fix on this). By way of explanation, I should also add that cruising boats like Flying Colours have the capability to flush overboard or into a “black water” holding tank, the behind-the-scenes plumbing and valves are rather complicated, with some of it “hidden” behind such things as a shower enclosure, or under a sink enclosure, or under the floor boards.

Rather than a water pressure problem that the Headhunter guy thought, Nate felt strongly from previous experience that our problem was a faulty electrical connection in the actuator circuit. He readily located three connections that might be suspect and re-soldered them. The head now worked, and Nate went about his long list of other boat repairs on the dock. Sure enough, within hours the head again malfunctioned, and after calling Nate back he discovered the actual faulty connection, resoldered it, and after three weeks as I write this, we have not had the problem reoccur.

My apologies for all this detail, but it just doesn’t seem sufficient to say that, gee, we got our battery, dinghy outboard motor, and guest head fixed, as that doesn’t explain why we were here at the Shearwater dock for another week.

In the meantime, Steve and Andrea on Couverden had arrived, giving us excuses for nightly Happy Hour get-together’s on Couverden to discuss next places to go. Since we’d last seen them, Andrea had discovered an old cruising map book in their chart table storage that dated from the days when Couverden (the Couverden I from 1985, and Couverden II from 1999) was repeatedly cruised to SE Alaska by her parents (when they were in their late 80s). In leafing through the atlas – with detailed navigation charts from Seattle to SE Alaska, Andrea saw there were dozens of handwritten notes by her father, Fred, describing good and bad anchorages, good and bad fishing spots, and other information gems. With our own chart books in hand, Kap and Andrea went over nearby places around Shearwater and Kap made similar notations in our books that could be of value to us.

Steve and Andrea were quite intent on staying somewhere close by to fish, prawn, crab, and dig oysters to fill their freezer chest for the winter, and they decided they probably wouldn’t get any further north than Shearwater. That left Kap and I to make the decision to go north on our own – which was OK.

Friday, July 20th, Shearwater Marina to somewhere north. On Friday, July 20th, we bid our farewells to Steve and Andrea and headed north – still not sure exactly how far north we’d get. Kap and I didn’t realize until we discussed it later that we both had some very real trepidation about crossing Dixon Entrance – the 50-mile open water section of the Inside Passage that separates Canada from SE Alaska. This was a big stumbling block for getting back to SE Alaska for the first time since 2008 when we cruised there in our Nordic Tub 42, Cosmo Place. The next couple of weeks will tell the story.

This is easily the most extensive resort/marina that we visit on the coast of British Columbia. The yellow building in the right background is the WWII flying boat hangar, and is now the shipyard. In front of it are the general offices, a marine chandlery, and a small grocery store. In front of that - and fronting onto the shoreline - is the pub, a full service restaurant/bar that serves breakfast, lunch, and dinner. The three buildings to the right are the fishing lodge. The grassy area is a ceremonial ground that commemorates the site for its WWII background, including the flying boat windsock. The long dock in the foreground is the visiting cruiser's dock (the blue boat on this side of the dock is an RCMP patrol boat that we see all the time up and down the B.C. coast - named the Inkster. Behind that dock is the commercial fishing boat dock - first come, first serve. At far left is a fuel dock - that has a line of boats all day long waiting to fuel. The treetops in the foreground are on Sheawater Island, a tiny island that all of this is named for.

So what’s the story with this place called Shearwater? We have to go back to the very early 1940s to find out the origins of Caucasian Canadians around here (before that, it was mainly First Nations people living in “old” Bella Bella on Denny Island).

As we all know, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on Oahu (HI) on December 7, 1941. What hasn’t been as well publicized is that just a bit over a week later (December 18-24), nine submarines of the Imperial Japanese Navy were prowling at strategic points along the Pacific Coast of both the U.S. and Canada. These submarine captains had orders to sink any U.S. Pacific Fleet ships if they managed to escape the Pearl Harbor attack and head for the mainland. They were also searching for U.S. merchant marine ships, sinking two and damaging two out of the eight that were attacked off the Coast – with a loss of six American lives. At least one of these nine submarines was spotted off the Central Canadian Coast, in Queen Charlotte Strait (near Cape Caution). (If you want to read more about this, a good account is at http://www.historynet.com/japanese-submarines-prowl-the-us-pacific-coastline-in-1941.htm).

But to get back to our story at hand. As early as 1922 there was aviation activity around Bella Bella, when U.S. Air Service pilot Lieutenant Harry Brown landed at Bella Bella to refuel on his flight from Seattle to Alaska – the first successful flight on the northern coast. Then in July, 1923, Canadian Air Force Squadron Leader Earl Godfrey landed a Curtiss HS-2L flying boat here to refuel on his historic flight from Vancouver to Prince Rupert.

This huge hangar was built for the WWII flying boats that were stationed here during the war. They now serve as the shipyard for Shearwater Marine. The erector set structure beside the dock ramp is a haul-out facility – the largest anywhere on the Central Coast.

The Canadians had long considered the Bella Bella area of strategic importance for West Coast flights. With the war clouds of WWII building, a military detachment was established here in 1938, on Denny Island, and protected behind Shearwater Island. In June 1940, construction began on a full-scale RCAF Station, with two flying boat hangars with ramps for beaching the aircraft, and accommodation for 1,000 men, and the accompanying support facilities (only one hangar survives today, and is the yellow Shearwater Marine Center building in the photo). By November, 1941 there were 21 buildings in the complex.

A day after the Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941, two Supermarine Stranraer flying boats arrived, and operational patrols began immediately when a Japanese submarine was sighted in Queen Charlotte Strait (Cape Caution is in the center of the Queen Charlotte Strait). Later, a squadron of Consolidated PBY flying boats were brought in, allowing patrols of up to 28 hours.

For some reason the overall area and the marina is called Shearwater, when in fact almost all of it is on Denny Island - and Shearwater Island is just a tiny island. Only the control tower for the flying boat operations was here on Shearwater Island. It’s a small island, barely a quarter mile in any direction, and totally uninhabited.

Let me digress for a good story that I ran across while researching for this. According to a history site about the RCAF Station Bella Bella (which was its official name), a dubiously bright station Commanding Officer, a Squadron Leader Galloway, decided that a control tower was needed on Shearwater Island and ordered its construction, but once completed the tower operators found that the tops of the island’s trees obscured their view. Galloway responded by ordering his Armaments Officer to top the trees with machine gun fire which worked fine but an army detachment across the bay had to take cover as their position was “peppered by the gunfire.” One would hope that Galloway wasn’t awarded any merits for his ingenuity.

This Shearwater welcome sign greets visitors at the top of the ramp to the floating docks. It’s on the edge of a park-like area that commemorates the men who protected the Canadian West Coast from Japanese assault during WWII. The carved grizzly bear is the finest example you’re likely to see, with detail that is just amazing. On a 25’ high steel pole sits a wonderful 17’ wingspan replica of a Supermarine Stranraer, in the markings of one of the two that were based here at RCAF Station Bella Bella – and it swivels as a windsock. Behind the grassy area is a 32-room lodge for the other major function of the resort – a guided sport fishing operation that takes guests out to the best fishing grounds for miles around.

But RCAF Station Bella Bella was short-lived. By mid-1944, risks from the nearly-defeated Japanese were low, and for economic reasons the station was closed. In 1947 the station property and facilities were sold to a former RCAF officer, Andrew Widsten, who had spent some time here, and whose Norwegian immigrant parents had settled in Bella Coola (not to be confused with Bella Bella, but rather at the First Nations village far up Rivers Inlet). Widsten’s vision for the former RCAF station was to create a marine services business to support boat repairs, sawmill services, and marine towing.

Today, through ownership by three generations of Widsten’s family, Shearwater Marine has 100 employees and is the largest employer on the Central Coast, with no government safety nets (i.e., no financial assistance), and no outside mentors. It’s now in the hands of Widsten’s grandkids, with the fourth generation being groomed to take over when the time comes. With all of the nearby cruising, anchoring, and fishing opportunities, this is not only a really neat place to visit, and for so many of us, a much-needed stopover on the way to/from other destinations on the Inside Passage – but it’s also a valuable asset to the region. It would be interesting to know what the place will be like 100 years from now – maybe a prosperous coastal town that grows into a city.