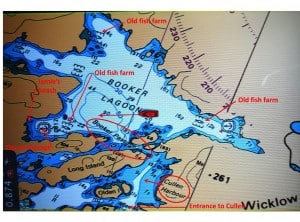

Our electronic course map of Booker Lagoon, showing our anchorage at the left. The passage into this wonderful lagoon is very narrow, with swift current when the tide is running in or out. This place must have been uninhabitable for cruisers a few years ago, as indicated by the fish farms in every arm of the lagoon - and none of them exist since we first came here to prawn four years ago. Fish farming of Atlantic salmon was widely done here by a Norwegian company (and was very controversial, as it was alledged that the farms created a parasitic hazard to the Pacific salmon that are critical to the region's economy). Since the fish farms have left, the area has become a good prawning ground.

Anchoring at Booker Lagoon – Oh, Oh . . . Windlass Failure! A cranky windlass – the thingy that raises and lowers the anchor – really got our anxiety level up last week as we settled into our favorite prawning spot at Booker Lagoon on the south side of Broughton Island. We had just arrived in Booker and got ourselves positioned to drop our anchor in the west arm of the lagoon. With Kap driving and me on the bow, I pushed the anchor-down button on the windlass remote control. In a crash of noise, the anchor dropped off the bowsprit and the anchor chain freewheeled at a mad pace. By the time I managed to get the manual brake locked down on it, over 50’ of anchor chain had pulled out (see what I mean about getting our anxiety up?). With the anchor now sitting on the bottom (and in the mud  below us), Kap and I fiddled . . . and discussed . . . and fiddled and discussed some more what our situation was. Our testing showed that our windlass clearly had a problem, apparently able to bring the anchor and chain back up, but wouldn’t “power” it down under the control of the remote. We determined that the only way to let out chain was to slowly let off the brake and let it freewheel of its own weight, controlling this by locking down the brake every few feet. We really prefer to power the anchor down, using the sprockets on the windlass to let it out under our control rather than freewheeling. With our predicament better understood, as Kap slowly backed the boat down in reverse, I carefully let out enough chain to give us our desired “scope” (click on the sidebar at right to see it enlarged enough to read), and then we “set” the anchor by letting it dig in to the mud.

below us), Kap and I fiddled . . . and discussed . . . and fiddled and discussed some more what our situation was. Our testing showed that our windlass clearly had a problem, apparently able to bring the anchor and chain back up, but wouldn’t “power” it down under the control of the remote. We determined that the only way to let out chain was to slowly let off the brake and let it freewheel of its own weight, controlling this by locking down the brake every few feet. We really prefer to power the anchor down, using the sprockets on the windlass to let it out under our control rather than freewheeling. With our predicament better understood, as Kap slowly backed the boat down in reverse, I carefully let out enough chain to give us our desired “scope” (click on the sidebar at right to see it enlarged enough to read), and then we “set” the anchor by letting it dig in to the mud.

We were pretty protected at our anchorage spot, so we figured a scope of 3 would be good.

If you want to see where we are now, or better yet, monitor our route progress as we cruise along, from the home page of www.ronf-flyingcolours.com click on the Current Location link in the upper right corner of the page. Also, this post is more readable in the online version, plus you can read any of the posts back to 2010 from the archive – just click on the link above to the blog. And don’t forget – you can click on any photo in the post to enlarge it.

Flying Colours serenly at anchor in the western arm of Booker Lagoon. She's lying in 40' of water, with a sticky mud bottom that grabs the anchor and chain like glue.

Booker Lagoon Prawning. From this ignominious start to our prawning, it’s no surprise that our fisher-person feats from that point on were only fair to middling. In a good year we’d get over 100 prawns in a “pot pull”, but this year the very best we had was 80, and the average over 17 total pulls was a piddly 30 – for a total of 507 prawns over a 6-day stay at anchor. Since first coming to Booker Lagoon about five years ago, this is the first time we haven’t reached our limit of 800 (400 per fishing license). But the good news was, the prawns themselves were larger on average than we’ve ever pulled up. In preparing the prawns for freezing in vacuum-seal bags, I sort them into small and large (the small to be used for Prawn Scampi and Prawn Cocktail, and the large for BBQ’ing), and whereas we normally get 2-to-1 (small-to-large), we got the same ratio numbers, but this time large-to-small.

Jamie has laid claim to this so-called beach as her best place to come ashore in Booker Lagoon. The trouble with it is, access to it is totally different at high tide versus low tide. It’s a gently sloping beach, so the rock hazards on the bottom are totally different with each visit by dinghy.

Jamie’s Beach. If you were a pup, knowing that you have to pee and poop a couple of times a day, wouldn’t it make sense to have your own “pup head” right on the boat, with artificial grass that looks just like the real stuff back home, and just steps from your favorite snoozing place in the sun?

Here’s the custom “pup head” that’s in the cockpit, and we keep trying to get Jamie to use it as such, but to no avail.

Well, Jamie won’t have any part of it. We brought this cool pup head on last summer’s cruise, knowing that Gator in his current health state would probably use it. Sure enough, at 16 going on 17, in failing health and virtually blind, he used it at lease a dozen times – and the times he wouldn’t/couldn’t, he simply did his “bidness” on the dock as I was trying to rush him ashore (and had to clean it up, then go back to hose the dock down).

Nope, since Jamie refuses to use it (and in fact, prefers to snooze on it – it’s been well washed since Gator used it). That means when we’re on anchor, we have to bus Jamie to the shore for her “duties” twice a day – a shore where we know there are black bears that drop by unannounced to savor a snack from anything they can find under a rock (I have photos from a couple of years ago of a bear that visited what is now Jamie’s Beach almost every morning).

These morning and evening trips also risk a dinghy outboard motor prop strike in the shallows. And that happened to us in this very same anchorage three years ago when we had to get Gator ashore during a storm. The rain and waves made it impossible to see the bottom as we got to the shallows, and sure enough we destroyed a prop (and had to have a replacement flown in from Seattle by Kenmore Air).

Time To Go. After six days and five nights of pulling the heavy pots with meager results, and then resetting them with lowered expectations, gave us a let’s-get-out-of-here perspective. We were tired of this, and decided to move on. Fortunately, the windlass brought the anchor up without problem.

We didn’t have cell coverage in Booker to place outgoing phone calls, but thanks to our satellite phone that I rarely use, we were able to book a marine repair guy in Port McNeill to work on our windlass. (And also, with a fix to our cell phone booster electronics that we had done over the winter, we were able to get a tiny amount of cell coverage that was enough to pull down e-mails on my iPhone – if I stood in the fly bridge, with my phone held high, and positioned exactly right for its internal antenna to “see” whatever tower it was picking up in the distance.)

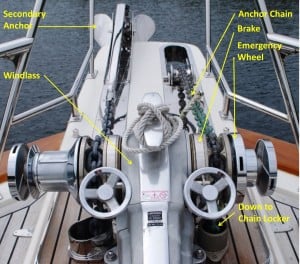

Our Lofrans dual-head windlass, with our primary anchor on the right half and a backup on the left. The brake is the silver circular thingy in front of the steering wheel-type brake control. The emergency hauler-upper is the outer two circular thingies, with slots around them that let you haul the anchor off the bottom with a large leverage bar in an emergency.

Port McNeill. As always, our friend Steve Jackman, owner of the North Island Marina and fuel dock, managed to squeeze us in for a 3-4 night stay, giving us a good chance to provision and get the windlass repair work done.

As promised, our repair guy, Graham McDonald, stopped by just before the end of the day to look at the windlass problem. After playing with it for a while and seeing what it was doing (or not doing), he scratched his head in puzzlement. He went home for the night with the windlass manual in hand, to study up on the windlass’ inner workings (lots of gearing and fiddly bits). Next morning, Graham returned and opened it up for an internal inspection (which didn’t quite go as planned, spilling a bit of oil from the unit’s reservoir on the teak decks of the bowsprit area – it can be cleaned up, but it’s a fair amount of work).

Several times Graham and Kap thought they had the problem figured out, but no cigar. Finally Graham’s attention turned to the solenoid, located inside a plastic case bolted inside the chain locker below the windlass. After playing with it a bit, Graham was convinced that a failed solenoid was the problem, and after reassembling the windlass he headed off for the day to order a new one. Unfortunately, by the time he got it ordered it was too late for it to be air freighted to us the next day, forcing us now to stay a fourth night at Port McNeill.

You might think this is just 21 ladies out for an evening exercise row after work – but you’d be wrong. Dragonboat Racing is big sport on Vancouver Island (and around the world). These paddlers are the Port McNeill Dragon Slayers, one of the top teams on the West Coast, of both Canada and the U.S. Paddling by us one evening, my photo snap caught the attention of the “sweep” who interrupted his steering duties to wave at me – he’s the only male on the 22-member crew. Races up and down the West Coast attract as many as 70 teams.

Our delay in Port McNeill wasn’t for naught, as half of one day was spent on laundry. We seriously needed to get four loads done, and while we have a stacked washer/dryer on Flying Colours, they are German design and each load takes a long time. The marina owner owns a laundromat just a half block from the top of the docks, and we make this one of our standard laundry spots.

Finally on Thursday, Graham showed up with the new solenoid (a price of C$318 was marked on the outside of the box, and we knew this didn’t include air freight charges). After a long while spent installing it and getting all of the wires hooked up correctly, the windlass still didn’t work (and in the same way as before). After determining that the problem wasn’t in the relays, Graham decided it had to be in one of the three remote controls – a handheld that plugs in near the windlass, one on the instrument dashboard in the pilot house, and one at the driving station in the fly bridge. Sure enough, when Graham unwired the two driving station controls, the windlass worked perfectly when operated from the handheld (which is what we almost always use to raise and lower the anchor). At this, Graham buttoned up his work, and to our surprise he said flatly that he was going to eat the cost of the replacement solenoid, and his entire repair bill came to US$380 (we were expecting it to be in the neighborhood of US$1,000). This is the second time we’ve had to call on Graham for repair work, and both times he’s done excellent work, and is just a prince of a guy.

Officially known as a “logging machine”, and commonly called a “donkey”, these behemoths were the workhorse of the Northwest logging scene. The steam boiler powered a large winch (the drum is on the right side of it), enabling logs to be hauled from the point they were felled, to the water’s edge where they were formed into log booms that carried them to sawmills or shipping ports. This one was manufactured by the Seattle Iron Works, and now sits almost ignored near the Port McNeill waterfront.

Steam donkey and relics of old logging days. We see evidence every single day of unbelievable natural resources – seemingly never-ending stands of native trees. Which leads me to the rape of the environment this caused during the past 150 years, yet also to the spread of civilization in these remote parts of North America.

Before the massive logging operations in Western B.C. (including Vancouver Island), there were 8.8 million acres of old growth forests (that’s equal to about 1/5th the size of Washington State). After the really serious logging operations of past years, the heavily forrested area has been reduced by more than 3/4ths, to under 2 million acres. And it continues, very evident to us in our cruising, with wide swaths of clear-cut hillsides visible along our route – although in a more managed way now.

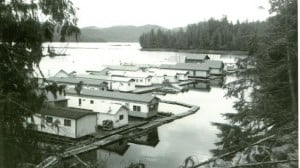

A typical floating camp that housed lumberjacks (a photo I cadged off the internet). There are no roads into these areas, and the easiest way to house and feed them was with these camps that were towed by tug from site to site as each logging site was finished and another to be started.

We see other evidence almost every day, particularly from the long-ago days when the world was simpler but work and living was harder. Many of the floating marinas and “resorts” we visit are echoes to that past, including their old buildings repurposed from the camps and floating villages that moved from site to site as logging operations moved. These camps housed hundreds of lumberjacks those who supported them, provisioned for their daily needs by ferries, mail boats, tugs, and barges that brought in supplies and kept them in touch with the outside world.

Blunden Harbour. The big question that we hadn’t settled since we left Anacortes over a month ago was, where should we go after the north end of Vancouver Island. As I’ve been saying for months now, the plan was to head for SE Alaska, but with our late departure in June, that would almost certainly put us into our southern return sometime in August, and we aren’t wild about the heavy fog in these regions at that time (August is called Fogust for a reason around here). Since our 2008 trip to SE Alaska, we haven’t been north of Port McNeill, so we were strongly favoring that, but we just couldn’t make up our minds how far north to go.

Blunden Harbour. The big question that we hadn’t settled since we left Anacortes over a month ago was, where should we go after the north end of Vancouver Island. As I’ve been saying for months now, the plan was to head for SE Alaska, but with our late departure in June, that would almost certainly put us into our southern return sometime in August, and we aren’t wild about the heavy fog in these regions at that time (August is called Fogust for a reason around here). Since our 2008 trip to SE Alaska, we haven’t been north of Port McNeill, so we were strongly favoring that, but we just couldn’t make up our minds how far north to go.

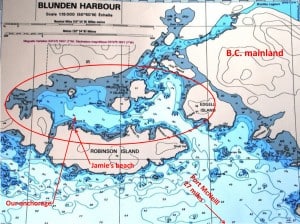

Finally, we settled on heading across Queen Charlotte Strait at the north end of Vancouver Island for a peek at Blunden Harbour. We figured to spend a couple of nights at anchor there – if nothing else, a good way to test out if our windlass was working properly. Once there, we’d put more mental effort into where to go next.

Not surprisingly, Blunden Harbour is every bit as pretty and peaceful as our cruising guides say it is. The entire inner harbor is quite large (maybe a mile from end to end, and about 800-1,000’ across, with a couple of arms that extend off it. It has a flat bottom of very thick mud, and the water depth throughout the harbor is less than 40’ – which means you can drop your anchor anywhere you want, and there’d easily be room for hundreds of boats (although we’ve never seen more than 4-6 on our two visits here now). Kap picked a spot that’s just off a shoreline indentation that has a really good “beach” that we can take the dinghy to with Jamie to do her business. We dropped our anchor, and as near as we can tell, the windlass worked as advertised.

Across to the other side of the harbor from our anchorage is a white sand-looking beach, but in fact it’s a shell beach (called a “midden”) where a First Nations settlement stood for over a hundred years (from the mid-1800s) – part of the Kwakiutl tribe that has since moved across to Port Hardy on Vancouver Island. There are still undiscovered artifacts throughout the abandoned village, and signs mark it with No Trepassing notices. In its heyday, the village had several hundred inhabitants, mostly involved in halibut fishing.

Across to the other side of the harbor from our anchorage is a white sand-looking beach, but in fact it’s a shell beach (called a “midden”) where a First Nations settlement stood for over a hundred years (from the mid-1800s) – part of the Kwakiutl tribe that has since moved across to Port Hardy on Vancouver Island. There are still undiscovered artifacts throughout the abandoned village, and signs mark it with No Trepassing notices. In its heyday, the village had several hundred inhabitants, mostly involved in halibut fishing.

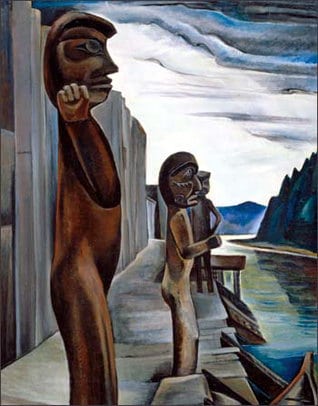

In 1930, a well-known Canadian artist, Emily Carr, created her most famous painting, titled Blunden Harbour, showing the boardwalk in front of plank houses, and with several welcoming First Nations figures at the shell beach.

In 1930, a well-known Canadian artist, Emily Carr, created her most famous painting, titled Blunden Harbour, showing the boardwalk in front of plank houses, and with several welcoming First Nations figures at the shell beach.

The bidden also features in the The Curve of Time, a book about coastal cruising from the 1940s by Muriel Wylie Blanchet that almost every cruiser in these waters has read at least once. By that time, the village was abandoned, although a couple of ramshackle buildings still existed. Now, though, few traces remain, and some fallen posts stick out from the grassy bank.

The seas aren't pretty as we rounded Cape Caution in 2008. The near boat (on the left) is UNDOC'D, and the far boat is ADMIRELLA. At Shearwater, ADMIRELLA stayed for salmon fishing and UNDOC'D continued with us as far as Ketchikan. We met up several times while in SE Alaska with Bucky and Christy Wood (he's a retired neurosurgeon in Birmingham, AL), and last saw them in Sitka.

Next stop. Fury Cove, a long cruising day (6-hours) from Blunden Harbour. To get there, we have to round Cape Caution – and its name is indicative of what’s involved in getting there – watch the weather and water conditions, and only poke your nose out if it’s good weather. This stretch of the Queen Charlotte Sound is one of only two open water sections of the Inside Passage between the southern tip of Vancouver Island and SE Alaska – and what I mean by that is, it’s open Pacific Ocean water all the way to Japan. With a 5,000 mile fetch, and with the weather marching across the Pacific from West to East, it builds to as much as 18’ rollers by the time it hits the coast of Western B.C. and SE Alaska. When we go around Cape Caution, we’ll be looking for waves no higher than 3’, and if we’re really lucky, calm as glass. (On our 2008 trip, we had 6’+ waves on the way north and glassy calm on the way south, and the latter is much, much nicer.)

P.S. Slight change of plans at the last minute. While taking Jamie ashore one last time before our departure from Blunden Harbour, the dinghy motor suddenly started putting out blue smoke from the exhaust. Since we’re heading into some quite remote anchorages (and maybe a remote moorage at Duncan’s Landing far up River’s Inlet), discretion says we should have it looked at. So, after the fog lifts this morning our new course plan is to head straight across Queen Charlotte Strait to Port Hardy to see if we can get it looked at. We haven’t been to Port Hardy since 2008 – at least, by boat – so it can’t hurt to see how the place has changed and use the time to get some fresh provisions too. (We weren’t too pleased with the marina that time, as it was our first experience with being kicked out of a marina on a bad weather day when we wanted to stay longer, and it resulted in us deciding to head for Cape Caution a day before we should have – and we paid for it with really rough seas all the way around.) (Caption: Rounding Cape Caution with U’UNDOC’D and ADMIRELLA on June 7th, 2008. The seas in this photo don’t look as bad as they really were – in fact, we frequently had 6’ waves that almost buried our bow. We buddy boated with ADMIRELLA as far as Prince Rupert, and with UNDOC’D all the way to SE Alaska, meeting up with them for the last time in Sitka. The Skipper (and crew) of UNDOC’D was a newly retired neurosurgeon from Birmingham, AL, Bucky Wood and his wife, Christy, and this was their first-ever cruise in their new 41’ American Tug. Our time spent with them at various places was very special, with so many great events that I should write about it someday.)