Hello all,

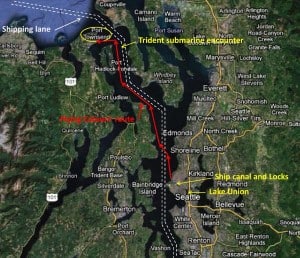

This last blog post for 2011 is going to be a wrap-up one, covering a wide range of topics that just don’t seem to fit anywhere else, plus an exciting little anecdote from our recent cruise in Flying Colours from Lake Union in Seattle to her home berth at Anacortes Marina. (Don’t forget – you can click on any image to enlarge it, and for this blog post, I think you’ll really want to.)

Passing through the Ship Canal we're always on the watch to see if the Pacific Titan is at the Western Towboat dock. Here she's rafted up to her sister ship, the Ocean Titan (Titan is the "class" name they give to this model of tug). I had the unique experience of cruising to SE Alaska as a guest aboard the Pacific Titan in 2003, and again in 2006 when Kap was also along. This is a story in itself, and best left to another time - but suffice it to say, it was one of the most memorable experiences in my life.

On the last day of the Fleming Fling at Seattle’s Elliott Bay Marina in early October, we moved Flying Colours through the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks and the fresh water of the Lake Washington Ship Canal. After this short cruise, we arrived at Yacht Masters NW at the north end of Lake Union, ready for our fall maintenance work. Over the next two months, shuttling between Yacht Masters, Pacific Yacht Management, and Level Sky Brightworks, we had the main engines and all other systems serviced, the teak cap rails varnished to look like new, plus some small fix-up work on various details.

The Lake Washington Ship Canal as it passes the funky Fremont neighborhood on the way into Lake Union. Behind us is Fisherman's Wharf and the waterfront area of Ballard called Salmon Bay. Ahead is the Fremont Bridge and the Hwy 99 Aurora Bridge.

By the first week of December, Flying Colours was ready for the journey to Anacortes where we could get her out of the weather and under the roof of our covered slip at Anacortes Marina. The challenge now was to wait for weather that was conducive to the trip.

At this time of year, the days are short at Seattle’s latitude – with sunrise about 7:45AM and sunset at 4:15PM – giving us barely 8½ hours of good daylight. At the speed we like to cruise at (9-10 kts), plus the transit time through the Locks, it’s problematic to make this trip in one day. Another significant factor in the route planning is slack tide at Deception Pass – it’s around 10-11AM right now, and impossible to reach from a Seattle start. The only option was a 2-day trip. Our first thought was to overnight at the new Port of Everett Marina, but when Kap plotted the second day’s cruise it was still impossible to reach Deception Pass in time for slack water.

Our route on the Ship Canal takes us past the funky neighborhood of Fremont, past Fisherman's Wharf, through the Locks, and out to Shilshole Marina.

An aerial shot of the Ship Canal, taken from the Hwy 99 Aurora Bridge at the NW corner of Lake Union, with the Fremont Bridge in the foreground. This is a very picturesque section of the Ship Canal, tree-lined on both sides for about a mile, with the newly completed Ship Canal Bike Trail (the overall bike path runs from the Seattle waterfront all the way out to Redmond).

All work on Flying Colours was complete on Friday, December 2nd, and the weather for the weekend called for cold temperatures (dipping into the 30s at night, and barely reaching the 40s in the daytime), sunny, and partly cloudy – it looked good to go. After discussing our options one last time, Kap chose a route that took us to Port Townsend on Saturday, then on to Anacortes on Sunday.

The iconic Lake Washington floating home that was the set for Sleepless In Seattle. There are hundreds of floating homes on Lake Union, in Portage Bay between Lake Union and Lake Washington, and along the Ship Canal that leads out to the Locks. Some are pretty dumpy, but many - like this one - are works of art inside and sell for well over $1M. It sits nearby our route from Yacht Master NW as we're heading towards the Ship Canal.

As usual, there were several rowing clubs on their Saturday practice runs along the Ship Canal. We always slow for them, to ensure that our wake doesn't cause them any problems - but we've heard that many other boats just blast on by them without any concern.

Departure from the Yacht Masters NW dock in Lake Union was set for 9:30AM for the anticipated 4+ hour trip to Port Townsend. The day before, while meeting with our architect team at our new home construction site, we invited them to join us on the trip through the Locks. This is usually a memorable experience, and one you can’t get unless you own a boat or know someone who does, so we thought it would be fun if they came along for the ride. We’d drop them off at the Shilshole Marina fuel dock, and the extra time for us would only be a few scant minutes.

Regan and Katie arrived right on time, and after a quick tour of Flying Colours and a safety briefing, we slipped our lines and slowly motored out of Lake Union and into the Ship Canal that leads to the Locks.

Along the way, we passed near to the Sleepless In Seattle float home on our left, then passed under the low Freemont Bridge and the tall, stately Hwy 99 Aurora Bridge. As we slowly motored along the mile-long tree lined section of the canal, there were morning joggers and walkers along the banks, as well as groups of rowers in racing shells, urged on by their coach in a nearby motorboat that follows alongside.

We always enjoy this part of the passage along the Ship Canal, as people sitting along the banks wave to you, and it’s just a beautiful sight to behold. It soon empties into a jumbled area of work boats – the type that I really like to look at – including fishing trawlers, large factory fish boats that station themselves in the fishing grounds to take on the catch from the smaller boats, with facilities on board to quickly cool the fish for the trip to Seattle. It’s a fascinating heritage of Seattle that always amazes.

Once under the Ballard Bridge, you pass Fisherman’s Wharf on the left – home of the Seattle fishing fleet – and a bit further on, are the docks that cater to the larger cruising boats, such as Westport. From there it’s just a few hundred feet and you’re in sight of the Locks.

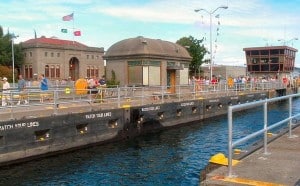

On a busy summer weekend day, the big lock might look like this - every bit of it crammed with pleasure boats, rafted to one another, with the boats along the lock walls tied to bollards - taking in or letting out line as necessary - along the top rail as the water in the lock raises or lowers (depending on which way you're going). In this particular photo, with the boats facing towards Lake Washington and the BNSF railway bridge in the backgound), water is being let in to raise the flotilla from the level of salt water Puget Sound to the level of fresh water Lake Union and Lake Washington. The green algae along the Lock wall shows how far the water level has to be raised to lake level. At the back of the lock, you can see that the hinged lock doors haven't yet been closed. (In the foreground of the photo, it would appear that the lock door is in the process of closing, but rather, this is the safety railing on the pedestrian walkway, and the photo is being taken from the level of the lake, directly above the lock door.)

At the Locks – officially known as the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks (but known locally as the Ballard Locks) – your blood pressure is always raised a point or two in anticipation, no matter how many times you’ve transited. Kap and I have now been through about 12-15 times over the past five years, but we’re still just a tiny bit nervous about them, as conditions are always different. Along the Ship Canal, Katie, Regan, and I got our lines and fenders ready for the Locks, and we briefed them on what to expect.

As you approach closer to the Locks, you typically never know whether you’ll get the large or small lock – and a red/green light system at the entrance to each lock notifies you which lock you’ll be directed to. Unless one of the locks is actually loading at the time you arrive (in which case it will show a green light), you’ll typically see red lights for both locks (and binoculars are particularly handy to know exactly what you’re looking at). If you see red for both locks, the procedure is to stop far enough back from the lock entrance to let boats leaving the lock get by you (when it opens), or slowly mill around, or tie up to the long pier in front of the lock – whatever makes the skipper more comfortable. This morning, there were no other boats milling around, both lights were red, so it’s a situation where you wait to see the green light.

This photo, taken from the pedestrian viewing area on the small lock shows the moving side walls. When using this lock, you tie your boat's lines at the bow and stern to the small round cleats in the moveable wall indentations. On the large lock, your lines would be tied by the lock master to very large yellow bollards (much larger than the one shown in the lower right of the photo). The Locks date to 1917, which can be seen by the architecture of the buildings.

The large lock is just that – large – 825′ long by 80′ wide – big enough to hold a half dozen very large fishing boats or ocean-going tugs, or at least 10 boats the size of Flying Colours, or maybe 50 small pleasure boats (as shown in the nearby photo). With the large lock, you tie onto a large bollard along the top level of the lock – where 2-3 lock masters are stationed to help you. If you’re arriving from the Puget Sound level (which is usually 14′ lower, depending on tide level), they throw down a small line at your bow and stern, which you’re then expected to attach your 50′ mooring line so they can pull your line up to attach to the bollard. If you’re arriving from the Ship Canal level (which is at the same level as the top of the Lock), the person at the bow and stern just hands across the lines for the lock master to tie on. Once the massive lock gates swing shut, water is flooded in if you’re rising to lake level, or drained out if you are lowering to Puget Sound level. The line handler’s job on the boat is to either play out line if you’re going down, or take in line if you’re going up – all the while keeping the lines tight enough so the boat remains close to the wall. The wall is covered with slimy green algae (which you can see in the accompanying photo) – which you certainly don’t want to touch – and which you also don’t want your boat rubbing against, so it’s imperative that you have enough fenders out.

If you get the small lock, the whole process is simpler, but not as exciting. The small lock is, well, small – 150′ long by 30′ wide. Once in the lock, the lock master tells the person handling the bow and stern lines which small round cleat along the side wall to tie to, and as the lock is raised or lowered, the wall raises and lowers with you. It’s easy-cheesy, and actually sort of a disappointment that there isn’t more excitement to it. From a boat owner’s perspective, though, the small lock is preferred, as it presents less risk of damage, and since there are almost always visitors standing around watching your every move, there’s less risk that you’ll embarrass yourself.

This time, we got the small lock, and as soon as we spotted the green light for it, Kap started motoring slowly into it, careful not to get too close to the sidewall until we were ready to tie on. Regan worked the bow line, while I took the stern line. We were the only boat in the lock, so as soon as we were tied on, the huge lock gate behind us creaked to a close, and we started down as the water in the lock tank was released. Within 4-5 minutes we were at Puget Sound level, and after a continuous buzzer rang to alert lock masters and visitors alike that the gates in front of us were about to open, they swung out and we were ready to go. The lock master always has you release the bow line first – for better control of the boat as it starts to move – and then the stern line is released.

From the Locks, it’s a quick half mile cruise to Shilshole Marina, where we pulled up to the fuel dock, momentarily tied on, and Regan and Katie jumped off. Kap backed Flying Colours into the main fairway of the marina, and soon we were on our way.

We left Shilshole just as the tide was switching from high to low – so the waters of Puget Sound would be flowing north (i.e., back to the Pacific) – which gave us a following current almost all the way to Port Townsend. It was about a 2 knot “push”, allowing us to maintain our 9 kts speed at a much lower RPM (thereby saving diesel fuel).

Along the way, there wasn’t much out of the usual, At first, we cruised along the east side of the shipping lane that runs down the center of Puget Sound, but we crossed over to the west side of it as we approached Port Madison. The commercial shipping lane is a controlled section, with a northbound lane on the right side, and a southbound lane on the left – and with huge tankers, freighters, and container ships running at over 20 knots, pleasure cruisers treat it with respect, and when you cross it, you do so smartly and don’t doddle.

Another obstacle to watch for on this route is the cross-Sound ferry that runs from Edmonds to Kingston, as they also run at 20+ knots, and have the right-of-way over us. We got lucky this time, with the eastbound and westbound ferries passing well in front of us, and as we crossed the ferry route they were both in port.

Our first glimpse of the Trident submarine, with its protective arsenal ships flanking it. They were probably a bit over a mile in front of us when I snapped this photo.

Just as we were passing Point-No-Point (on the west side of the Sound, just before you turn into Port Townsend), Kap hollered to me that we might be getting a chance to see our first-ever Trident submarine cruising past us in Puget Sound. Ahead of us about two miles were two really strange-looking – boxy, actually – Navy ships, heading towards us in the center of the shipping lane. Between them was something that looked like a sub conning tower, but it was too far away to see clearly. As we got closer – we were on the west side of the shipping lane – flanking them were three smaller boats that looked like fast cruisers. I snapped a photo, figuring that I might be able to blow it up to see better.

As we got closer we could tell for certain it was a Trident sub, and we then heard the following radio transmission on Channel 13 – “Pacific Mariner (rf – a Western Towboat tug and tow that was behind us about a mile), this is a Navy submarine 9,000’ ahead of you.” No response. Within a couple of minutes, the sub then called on Channel 12 “Seattle Traffic, this is Navy submarine (rf – but didn’t identify himself more than that), we have a tug and tow in front of us in the shipping lane approaching us and it appears he’s not conforming to the northbound lane of the shipping lanes – can you confirm that he’s a bona fide vessel, and can you reach him on VHF to have him clear to the outside of the northbound lane.” At that point we certainly knew it was a sub heading towards us.

The Trident submarine and its entourage is abreast of us, with the larger Coast Guard boat shadowing us to ensure we don't make any stupid moves.

At about that same time one of the go-fast boats – by now we could recognize all of them as Coast Guard boats – headed straight towards us at full speed, with their blue lights flashing. When he got to us – Kap had already stopped dead in the water – they spun around to the same direction we were going, and called us on Channel 16 , “Flying Colours, this is the Coast Guard vessel on your starboard side . . . please switch to Channel 22”. As soon as we switched, he then proceeded to tell us, “Captain, U.S. Navy and Coast Guard regulations require that you stay at least 3,000’ in every direction from a submarine of the U.S. Navy. There is a submarine passing on your starboard side.” As if we didn’t already know……

We both took a look at our radar screen, and it appeared to us that we were about 4,000’ away from the radar blip that was obviously the submarine, so we should already have been OK. We didn’t argue the point, as it was also obvious from their radio transmissions that they meant business, and we could clearly see they had automatic weapons in hand. So Kap responded that we understood, and she powered up our speed to move further away, but we were still pretty much parallel to the sub’s path. The CG vessel then turned and went on its way. Within moments, though, another (and larger) of the Coast Guard boats hit the throttle and headed for us. They spun around about 100’ from us and just shadowed us until the sub was well behind us. They then turned around to rejoin the flotilla. While they were flanking us, I got up the nerve to snap a photograph of the second CG boat, with the Trident in the background.

This is an aerial starboard bow view of the Michigan, SSBN-727 (which I grabbed from http://www.navsource.org/archives/08/08727.htm). I was on the Michigan in 1999 during a one-day shakedown cruise from the Trident sub base at Bangor, WA. Kap was also on a shakedown cruise a couple of weeks earlier than mine, but on the Alabama (but that again is another story, to be told elsewhere). Our trips were arranged by a neighbor (Bob Tate) who is a retired Navy captain. The Navy used to allow guests on board – about 15 in a group – on the mandatory one day shakedown cruise at the start of each 6-month cruise. During the day, we were given a tour of the entire sub – except for the bottom deck where the nuclear propulsion reactor is located – including up on the outer top deck at one point when we were on the surface. We dove to 100’ in Dabob Bay, we each got a chance to look through the conning tower periscope, and we got to climb up into the conning tower. This sub is huge – over 900’ long, with a diameter of over 40’! There are four decks – which isn’t what you think of when you see a sub in the movies – and get this, the 18 multiple warhead nuclear ballistic cruise missiles carried on board are about 30' tall, and stand vertically, rising straight up through three internal deck levels. They’re fired from this standing position, and shoot up through big (5-6’ across) manhole–looking covers on the deck. The most impressive thing of all, though, was the crew – as we departed the dock at Bangor that morning, we watched as the crew said goodbye to their families, knowing they were heading out on a six month cruise where they’d be submerged the entire time, with no in-port time – and the morale was unbelievable! At the end of the cruise, the sub returned to the sub base area, but didn’t dock – we were piped aboard a Navy tug that pulled alongside, and the sub quietly slipped out towards its cruise. This is one serious piece of military machinery, and I’m sure glad it’s in our arsenal!

We went on our business and into Port Townsend. After mooring at the guest dock, we went to the marina office to register and pay for our moorage. As we were chit-chatting with the marina manager, I mentioned our encounter with the Trident and the Coast Guard. He chuckled knowingly, saying that this is now common practice since 9/11 – that Tridents don’t venture out into Puget Sound anymore without escorts like this, particularly when they have nuclear missiles on board, and that they were undoubtedly heading for the ammo dump just south of there to offload them before they headed over to Bangor. He went on to say that it’s a good thing we responded on the first transmission on Channel 16. If you don’t, he said they fire something called a “sound blast” (I think that’s what he said) over your bow. I’d never heard of this, and he explained that it’s a cannon-like shell that’s fired over your bow, and as it passes over the sound blast from it is enough to knock you to the ground. I guess that’s their way of getting your attention. He also indicated that what’s on board the two escort ships next to the sub is enough munitions to probably blast the Pacific Northwest into oblivion (I would imagine what happened to the USS Cole in Yemen is the cause of this). Needless to say, this was all a bit unnerving.

Port Townsend was great at this time of year, with the main streets (all two of them) all decked out with Christmas ornaments. It was surprising how many people there were on the street, and the shops were busy – and we soon found out why. There was a Santa parade down the main street, and it brought the whole town out. We had a wonderful dinner at an old pub/saloon on the main street, with a bottle of very good local wine. Afterwards, we headed back to Flying Colours to get warmed up.

Early Sunday morning, we headed out of Port Townsend for Anacortes. It was another four hour cruise, and we wanted to be at our slip in time to get the kayaks offloaded and stored for the winter, and to tidy things up for a last fall clean-up before putting Flying Colours to bed for the winter. Before we got to our marina, we stopped off at the Cap Sante Marina fuel dock to top off our diesel tanks. It took just 122 gallons to top them off, but the pleasant surprise was that the price for diesel is down to $3.68/gallon (which still seems like a lot, but compared to the $5.75/gallon we paid on our cruise to SE Alaska in the Nordic Tug in 2008, this is a bargain!).

I hope you enjoyed the blog this year as much as I enjoyed writing it. It’s proven to be a really good way to get my thoughts down on paper, and a way to remember the things that we’re doing.

Happy Holidays.

Ron