The northern half of the Inside Passage is defined by long, straight, narrow channels that begin at the southern end of Swindle Island (a good name that makes you wonder about its origin). Halfway up Finlayson Channel you can either continue or shunt off to the more narrow Tolmie Channel - particularly if you want to stop by at Klemto village.

Friday, July 20th; Shearwater Marina to Butedale Cannery. In 2017 our furthest northern point on the Inside Passage was Shearwater (and the visit didn’t leave a very good taste with us). Striking off northward from Shearwater was a clear indication that this year might be different. We just decided we’d see how things go, and with lots of time still on our schedule, take it a day at a time. At least, that was our overall plan – but more immediately was a concern about ZuZu, which I’ll explain in a bit.

Don’t forget – you can click on any photo in the post to enlarge it.

Tug and tows are commonplace in this part of the world – but it grabs my attention when it’s a triple tow, considering that “little” tug (probably an 80-footer) at the far right is towing three large barges that each dwarf it, weighing thousands of tons – and doing it at nearly the speed we’re going. It took us forever to catch up with this “water train”, and it helped when we cut a corner on the inside of him as we rounded a buoy. We’re in Millebanke Sound at this point, and while it's a short stretch of open Pacific waters it isn’t bad. The seas are a bit lumpy, with swells of 5’-6’ that come in every 10-15 seconds. In the background is Price Island that we’re just starting to get some protection from heavier seas. All morning long we had low clouds and a touch of fog to contend with.

During preparations for our departure we outwardly said very little about whether we’d even make it to Prince Rupert, let alone to SE Alaska. Rather, we spoke in terms of maybe getting as far as Prince Rupert – the furthest north town/city along the B.C. coast. And given the boat and system problems we’ve been having of late, maybe we wouldn’t even get that far.

Nevertheless, just getting out of Shearwater and finally beginning our northernmost cruise in ten years was very cathartic. As we headed west on Seaforth Channel there were quite a few fishing boats from the Shearwater/Bella Bella area – a good sign that the salmon run was finally starting. We slowed our route through there to keep our wake down for the small fishing boats – which is something a lot of cruising boats don’t do (even though the captains of many of those boats probably curse the wakes when they’re out there in their own small fishing boats that they tow behind them.

If you want to see where we are now, or better yet, monitor our route progress as we cruise along, you can go to www.ronf-flyingcolours.com and click on the Current Location link in the upper right corner of the home page.

Also, this post is more readable in the online version, plus you can read any of the posts back to 2010 from the archive – just click on the link above to the blog.

Now that we’re in serious Spirit Bear country, our eyes are constantly scanning the shoreline for rocky areas where a bear might come for breakfast. And Spirit Bears are everywhere! Is that white spot over on shore a spirit bear??? As soon as we put the binoculars on ones like this, they turn out to be false – and nothing but a bleached log or a white-tone rock.

As we passed Ivory Island on our starboard it marked the entrance to Milbanke Sound – and another bit of Pacific Ocean-exposed Inside Passage that can be very rough with ocean rollers and waves coming in. Today it wasn’t too bad – maybe 5’-6’ rollers and waves around 3’. At least we didn’t have heavy fog, and that made the going a lot more pleasant.

After all, doesn’t the possible Spirit Bear in the photo above look just as real as the one in this photo – which is a photo of a real Spirit Bear that we spotted on Bell Island north of Ketchikan in 2008. This Spirit Bear sighting was covered extensively in my blog post of July 25, 2014, House Bank – Depositing Boat Units.

It took about an hour to get to the protection of Price Island, as we turned north towards Swindle Island. For me, the entrance to Finlayson Channel is a major turning point on the Inside Passage, where there are a series of long, straight, narrow channels. It’s my mind’s-eye image of what the Inside Passage is really like – cruising mile after mile with steep and heavily forested mountains on both sides of the channel.

In this photo we’re cruising in Finlayson Channel, on the east side of Swindle Island, with the telltale Cone Island (also known as China Hat) that marks the entrance to Tolmie Channel, a side waterway that leads to the tiny First Nations village of Klemtu. The large boat we were about to meet was baffling us – too small to be a ferry, but seemingly too large to be a cruiser. Maybe a research vessel of some kind?

We were starting into Spirit Bear country – from here up to the northern end of Princess Royal Island – so we kept several pair of binoculars at close hand, including a special one that has a battery-powered stabilizer focus – that I bought for the 2003 tug and barge trip to SE Alaska (with which I didn’t manage to spot a single bear on the entire trip).

The mystery boat is named Scout II, and while it’s almost certainly owned by a rich American, it’s flying a flag from some tax haven island in the Caribbean – a sure sign that the owner of this megatub is skirting his/her fair share of U.S. tax laws. This is one of our pet peeves, as we all rely on government facilities when we’re on the water, such as weather service, Coast Guard, search and rescue, fisheries, and on and on. It’s deadbeats like this that make things more expensive for the rest of us – yet somehow they claim it’s because they are already taxed too much.

Our original plan had been to stop at a tiny First Nations village called Klemtu (number 8 on the Central B.C. map above). We’d stopped there overnight on our 2008 trip on Cosmo Place, and with a special tour of their brand new longhouse, it was one of our most memorable days of the entire trip. Our only negative of that stop was how depressed all of the First Nations people that we met on the streets seemed to be – sullenly walking along, everyone with iTouch ear buds in their ears, and not even interested in a greeting. Now, though, we’re told that the village elders have really turned things around – and the longhouse was a big factor in it – by engaging the young people in learning to appreciate their culture and heritage. The local school kids are taken on a weekly field trip to visit other First Nations villages up and down the coast, at cultural centers such as Alert Bay near Port McNeill.

This new ecotourism lodge at Klemtu must be a huge boon to the economt of this small First Nations village – but who knows if it’s a good or bad thing in a larger sense. The lodge sits very close to the water’s edge, and from the website gallery it appears that almost every room has a good view.

The big change at Klemtu, though, is the opening of a large, 5-star ecoadventure lodge, called Spirit Bear Lodge (at www.spiritbear.com). There was a major article about the spirit bear in National Geographic in December 2017, titled What’s Black, and White, and One of Earth’s Rarest Bears? If you don’t subscribe to National Geographic, you can see a advertisement for the article, including a great video clip of their hunt for this rare bear: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2017/12/basic-instincts-spirit-bear/. Supposedly, there are around 400 spirit bears in and around Princess Royal Island, yet every cruiser we talk to who’s been to SE Alaska has never see one. We are very lucky to have photos to prove of our one sighting.

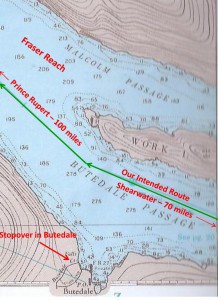

When you scroll out to see the bigger picture of the route, these channels really come into perspective – long, narrow, and relatively straight (in fact, zoomed out it hardly looks like Flying Colours will fit in them, but in fact, they’re typically 1/4-1/2 mile wide. This section of the chart is just north of Kelmtu. Flying Colours is the green boat symbol at the bottom, with a long blue line showing our intended course direction. The green line is the day’s course plugged into the navigation software; the little square boxes – with a dot in the center – are waypoints, and the software gives us times and distance to each. On the chart this channel looks to be very narrow, but in fact it’s probably a quarter to half mile wide, with mountains that come right down to the water’s edge. At the top of the chart is Butedale Cannery, our intended moorage for the night.

But a stop at Klemtu this summer was not to be. On our last full day at Shearwater a serious ZuZu injury occurred – or at least, that’s what we thought. While I was at Bella Bella getting some last-minute provisions, Kap stayed back on Flying Colours with Jamie and ZuZu. She suddenly heard a loud crash in the fly bridge and when she went to explore its origin she found ZuZu seriously lame and not able to put any weight on her left front leg or paw. This is the leg that’s been troubling her for several months now, and her regular vet back home diagnosed it as arthritis in her left front shoulder. She’s been on a medication called Meloxicam (or Mobic, depending on brand name or generic – and which is exactly what I took for several years before I had my partial knee replacements). This time, though, ZuZu was acting so lame and her left leg projected out at a funny angle that Kap thought she’d dislocated her shoulder or broken a bone. We seriously discussed whether to return to Port Hardy (where we know there’s a good vet) or continue north to Prince Rupert – either way, as expeditiously as possible. Prince Rupert is quite a bit larger (population 12,000 versus 4,000), and we figured if we headed south for vet attention it would likely mean our northward momentum would be over. We opted for Prince Rupert, and to get there as soon as we could.

They don’t get more picturesque than Boat Bluff Lighthouse, on Tolmie Channel just before Klemtu, at a sharp S-turn. With a narrowing pinch point, the area not only creates a rushing current and whirlpools, but also channels and accelerates the winds – which is why there’s a lighthouse/reporting station here. At first, we thought the tombstone-shaped “things” below the lighthouse keeper’s house were just that – maybe a cemetery of previous keepers – but as we got closer we could see it was a maze of round concrete foundations that probably stabilize the hillside to protect the house. It’s interesting to note the tide level – probably mid-tide – and high tide would be where the rocks at the right turn from dark to white-ish.

In the meantime, we had some powerful meds for ZuZu that our regular vet back home had given us for just such an emergency – mouth-injectable pre-loaded gizmos that contained a precise amount of a drug called Buprenorphine. We had about 10 of the injection/squirters with us, but we found that one-a-day would almost completely sedate her, plus keep the pain manageable. (It was only later that we learned Buprenorphine (prescribed for humans under the brand name Buprenex) is “30 times more powerful “at relieving pain” than morphine”, according to a website called VetInfo. The site also told us that “cats usually react negatively to opiates, but Buprenorphine is an exception”. At this point we gave a dose to ZuZu each morning and it would knock her out for the entire cruising day, and the after effects would seem to keep her comfortable through the night as she slept on our bed with us.

As a result, we bypassed Klemtu, and after a lot of discussion we opted to push on to Butedale. It’s a ramshackle old fish cannery that’s a further 25 miles up the channel, known to be in total disrepair, but our cruising guide indicated the dock was in slightly better shape than in previous years. And while other cruisers often stopped there for a free night’s moorage, we thought we might be able to find space for Flying Colours, and that would get us a much-needed 25 miles closer to Prince Rupert.

Shawn Kennedy, a retired mining engineer from Calgary and the present owner of the Butedale Cannery and the surrounding land (plus all of the water rights leading out of the lake above and behind the waterfront), is either a visionary or a fool who’s parted ways with his money. This is his business card that he handed me as we discussed his hopes and dreams for the future - and he's really serious and passionate about the future of this place.

Butedale Cannery. What a pleasant surprise! There’s no question . . . at the present moment, the Butedale Cannery is at least as derelict as anything you might find along the B.C. coast. (The photo that Shawn used on this business card was clearly taken at a time when the cannery was still in operation.) But before I can go any further on that, a bit of history is in order.

On our approach to Butedale Cannery, there’s one sailboat at the dock, and at the left of it is a derelict little speed boat next to a yellow can buoy that seems to be anchoring the dock (maybe to keep it from floating away). At far left – the large building on pilings, and has water under it at high tide – is the original fish cannery facility, and while it’s in serious disrepair, it could probably be renovated (we toured a similar one a few weeks later, and everything about it is stout enough that it’ll take another 100 years for it to totally decay, although a bunch of the pilings would have to be replaced. Inside of the dock we tied up on is an extensive array of pilings that had a row of community buildings on it. Nowadays, and right where the sailboat mast is, there’s a makeshift heliport deck – that Shawn seems quite proud of, and says he’s used it several times to fly in and out. On shore, most of the original buildings have been pulled or fallen down. The current owner lives in the small house to the left of the red/white/red building – when he’s in residence. It’s hard to imagine this place with 300+ people living/working here.

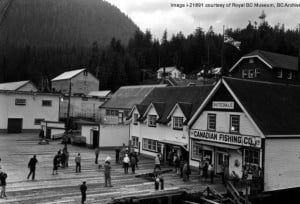

Butedale waterfront general store and post office. There’s nothing but pilings left of the buildings in the photo center, and the large building at far left is the main fish processing plant that we moored near – just a hulk now, but one that could probably be restored. This photo is from the archives of the Royal BC Museum.

Logging and salmon fishing have been the two main industries along the B.C. coast for over 100 years. The more we explore this coast, the more we realize that, as seemingly remote as it is now, it wasn’t always that way. Dating back as far as the 1880s, there were 100 (!) salmon canneries scattered along this coast, and each of them employed upwards of 300-400 people. At the same time, there were also hundreds of logging camps – with full-service “villages” built entirely on floats that enabled them to be towed from camp to camp as the logging sites changed – and each of these had populations that maybe stretched to 100-300 loggers and support staff. Externally to support all of this there were supply boats and passenger steamers that brought provisions and mail, and carried workers back and forth. All of that represents a huge difference in today’s total population.

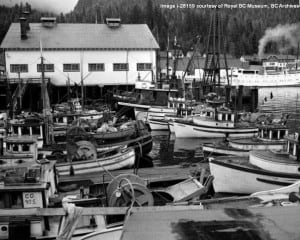

Fishing boats at Butedale Cannery in the 1920s. The tiny vessels with drums are vastly different from today’s highly efficient seiners and gill netters that we’re used to seeing – and the sheer number of these boats is very different. The foreground building in this photo is the opposite end of the derelict hulk near where we’re moored in my photos. This structure was almost certainly the main salmon processing building of the whole operation. This photo is from the archives of the Royal BC Museum.

Today, not a single cannery is in operation anywhere on the B.C. coast, out of the 100 that existed 50 years ago. Butedale has been declared a B.C. heritage site, which gives it some level of protected status even though it’s in serious decay. At its peak, Butedale Cannery employed 400 workers. That’s the size of a small town, and given the remoteness of it, would require a sizeable infrastructure to support it.

The numbers shown in the waters of the channel are in fathoms, where a fathom is equal to 6 feet. So out in the deeper water that shows 165-210 fathoms, the water depth is 990’ to 1,260’ deep. Along the shorelines where you see dotted lines, these are contour lines that show how quickly the water depth drops, from as shallow as 6 fathoms (36’) to 70-80 fathoms (400+ feet) in a matter of a very short distance from shore. This will become relevant when you read about Captain George Vancouver’s experiences right here.

As you can see from the accompanying map, Butedale is nestled in a U-shaped cutout near Work Island, where Graham Reach takes a turn around the island and becomes Fraser Reach. Shearwater is now 70 miles behind us, and Prince Rupert is at least 100 miles ahead of us. Our cruising guide indicates a new owner recently purchased Butedale Cannery and its surrounding property. While it’s closed for any kind of marina business, boaters won’t be turned away and mooring here is at no charge, and at your own risk. When we were 4-5 miles out we tried VHF channel 66 (the standard marina channel in Canada) to see if anyone would respond, and to our surprise we immediately got a friendly voice back that there was room on the dock and we were certainly welcome to moor for the night. We decided to give these decaying ruins a looksee.

Butedale’s new owner that we soon met, Shawn Kennedy, treated us like long lost friends on our arrival, and when I took Jamie to land for some much-needed shore leave, Shawn couldn’t wait to show me the photo of Flying Colours that he snapped with his iPhone on our approach. This is definitely a postcard photo, and it just might inspire me to write a family and friends “what we did in 2018” letter for this year’s holidays. Even enlarged, you can barely make out Jamie on the forward bow, directing us onto the dock.

As he showed me the photo of Flying Colours approaching the dock, Shawn excitedly told me the barest of details about his plans. He’s an ex-mining engineer from Alberta, and somehow managed to purchase not only the decaying remnants of the cannery, but also a large portion of the shoreline that makes up the U-shaped bowl, plus the land that extends to Butedale Lake behind, plus the water-use rights for all water coming out of the lake and cascading down the waterfall next to the cannery (from which he can generate enough electricity to power whatever he wants to develop). He said he has several “well-heeled mining friends” back in Calgary who are very interested in investing in whatever project is decided on – but for right now, what he’s concentrating on is cleaning up the structures that are in total disrepair (i.e., falling down), getting the dock in usable shape, and ridding the place of “its liabilities” (his words, whatever that means). What he’s most proud of – get this – is a heliport that he’s built on top of the pilings that are right next to the dock, and which he’s utilized several times. (An hour after our arrival, another cruising boat arrived, with Australian registration – yes, that’s right, Australian – and the guy on board spent the next three hours with Shawn looking over every bit of the property, and our guess was, he’s one of the well-heeled potential investors Shawn was talking about.)

Yes, we did manage to get over our concern and tie our very special Flying Colours to this derelict dock. (I seem to be using the word “derelict” a lot in this blog post.) And yes, the dock is listing dramatically to the left – the flotation under it needs some serious repair, as do many of the boards on the dock surface itself. It’s so unstable that it rocks from side to side as I’d take each step. At the stern of the sailboat ahead of us, there was a 15’ gap in the dock, with a set of boards that shunted me (and Jamie) off to some temporary boards sitting atop the large logs. Above the pilings is the heliport. During our overnight stay here, Kap never did go ashore (and probably for good reason),so taking Jamie ashore three different times was a solo task. The fjord-like mountains in the background are on the other side of Fraser Reach, with low clouds over them.

Yes, we did manage to get over our concern and tie our very special Flying Colours to this derelict dock. (I seem to be using the word “derelict” a lot in this blog post.) And yes, the dock is listing dramatically to the left – the flotation under it needs some serious repair, as do many of the boards on the dock surface itself. It’s so unstable that it rocks from side to side as I’d take each step. At the stern of the sailboat ahead of us, there was a 15’ gap in the dock, with a set of boards that shunted me (and Jamie) off to some temporary boards sitting atop the large logs. Above the pilings is the heliport. During our overnight stay here, Kap never did go ashore (and probably for good reason),so taking Jamie ashore three different times was a solo task. The fjord-like mountains in the background are on the other side of Fraser Reach, with low clouds over them.

I snapped this photo from the new aluminum dock ramp where I took Jamie ashore. Behind the railings that hold the Butedale and 66A signs is the heliport that sits on what appears to be very ramshackle pilings that probably date to the early 20th century. While a bunch of them need to be replaced, the majority are probably still sound. The structure is probably one of the original buildings in the first archive photo above. At the far right of the photo, the orange “thing” is a scoop shovel/backhoe that Shawn brought in to clear rubble. The Butedale Lake is to the right and behind; to the left – and for at least a quarter mile – is the shoreline that Shawn also owns. There’s room in this bay to create an extensive array of docks, plus an anchoring area for overflow.

As I went about our tasks securing Flying Colours – not to mention a Happy Hour wind-down – my mind was racing with the possibilities of this place (I’m resigned to the fact that I’ll never stop being an entrepreneur). The old cannery building is in pretty bad shape, all of the other structures on shore are in sorry shape, and the dock is in horrible shape. But what could $5M, $10M, or whatever, do to get this place in operational shape? From Tolmie Channel in the south, to Grenville Channel at the north end, this is a main waterway of the Inside Passage, with a large BC Ferry on the route between Prince Rupert, Bella Bella, and on south to Port Hardy. And with hundreds of cruising boats passing in both directions, not to mention similar numbers of fishing boats heading to and from the Alaska fishing grounds – and with our dilemma in finding a place for the night along this 170 mile stretch of remote channels . . . well, a multi-purpose marina has to be viable here. And If the cannery once supported one of the premier commercial fishing spots in the region, it could also support a high end sport fishing camp for well-heeled guests who fly in for a week or two. Thoughts of it almost made me want to be one of his well-heeled mining friends from Alberta . . . and I couldn’t help but think about what this place might look like in another hundred years. But enough of these fanciful dreams and speculation.

Oh, one operational detail. This was our first night without shore power since the two new batteries were installed. Kap and I are convinced that our overall battery power is stronger, for longer, than it was 3½ years ago when the entire house bank was replaced. It makes us wonder if one (or both) of the two recently failing batteries had a problem from the start. We’ll never know, but it’s an interesting idea.

This early morning photo was taken just as we departed Butedale Cannery and getting our position established with the best current on Fraser Reach. On the navigational charts a channel like this looks narrow, and with perfectly smooth shorelines. Instead, tiny shoreline indentations on the chart translate to fairly large jogs in the real shoreline, and layers of ridges give it overlapping appearance. And what looks narrow is really a substantial body of water.

It was almost certainly somewhere in this photo at the right that the following occurred around 200 years ago.

So, How Much Fun Was Captain George Vancouver Having Here in the Summer of 1793? Not much, I suspect, and in fact, rather than being aboard the Discovery and Chatham ships under his command, Vancouver (and all of his men) would probably have preferred to be in England right now.

Here’s a passage from the Evergreen Pacific Exploring Cruising Atlas – Alaska/British Columbia, by Stephen E. Hilson – an historical cruising guide that we carry on board and reference whenever we want to find out the history of what we’re cruising through. Every indication from the following account shows that cruising these waters, not only here at Butedale, but everywhere from Puget Sound to SE Alaska, in primitive ships of the late 1700s was brutal, incredibly hard work, and fraught with life-threatening dangers.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

“Saturday, June 29, 1793

As the English ships Discovery and Chatham fight their way up the waterway from Work Island [RF: which is just outside the bay where Butedale Cannery is] the tide begins to turn and threatens to push them back. Vancouver writes in his journal, “. . . and the steepness of the rocky sides afforded little prospect of obtaining any anchorage on which we could depend for the night. We had repeatedly traversed from shore to shore without finding bottom with 165 and 185 fathoms of line, though within half of the ship’s length of the rocks [RF: a fathom is 6’, so that’s 990’ and 1,185’, respectively – which is probably quite a bit deeper than any anchor chain they had aboard the ships – the Discovery itself was 99’ in length, so being half that distance from shore meant they were finding these depths at 50’ from the shore]. The tide now making against us, we were constrained to rest our sides against the rocks, and by hawsers fastened to the trees to prevent our being driven back. Our present resting place was perfectly safe, but this is not the case against every part of these rocky precipices, as they are frequently found to jet out a few yards, or at a little beneath low-water mark; and if a vessel should ground on any of those projecting parts about high water, she would, on the falling tide, if heeling from the shore, be in a very dangerous situation.

The weather was foggy for some hours the next morning, and was afterwards succeeded by a calm, this in addition to an unfavorable tide, detained us against the rocks until about noon, when a breeze from the westward enabled us to make sail, though with little effect. In the afternoon the breeze again died away; but with the assistance of our boats, and with an eddy tide within about fifty yards of the rocks, we advanced by slow degrees to the westward, and found soundings from 45 to 60 fathoms [RF: 270’-360’], hard rocky bottom, and about a half a cable’s length from the shore; but at a greater distance no ground could be gained. In this tedious navigation, sometimes brushing our sides against the rocks, at others just keeping clear of the trees that overhung them, we had advanced at midnight about four miles; and having, at that time, bottom at the depth of 45 fathoms [RF: 270’], about forty yards from the shore, we let go of the anchor; but such was the projecting declivity of the rocks on which the anchor at first rested, that almost instantly slipped off into 60 fathoms [RF: 360’]. By this time however a hawser was made fast to the trees, and being hauled tight, it prevented the anchor slipping lower down, and just answered the purpose of keeping us from the projecting rocks of the shore.”

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Having cruised this area for a dozen years, and with the relatively mild experiences we’ve experienced, I find Vancouver’s description about his challenges here to be harrowing. As we cruised along, Kap and I certainly felt comfortable being in the middle of this channel, but the thought of putting Flying Colours up against the rocky shore and lashing the boat to trees at the water’s edge for the night would be terrifying! (not to mention, unthinkable!) Granted, on Discovery they had a bit over 100 sailors on board (versus just the two of us), but the dexterity and bravery required to get big hawsers around the trees and back to the boat just seems like a recipe for disaster. And they’re dealing with huge anchors weighing several hundred pounds – and with no hydraulics or electric motors to assist them. They faced powerful winds and currents as we too experience around here, but they had to contend with it with nothing but sails and oars.

As a final note about Butedale, there’s an Author’s Note in the book about Butedale Cannery: “In 1973 this author found the cannery operations in the bay had been abandoned, a few logging families were living in the homes (including some blushing newlyweds to whom we contributed our ship’s wheel mirror), the store was almost empty, and the fuel pumps looked about to sink on a rickety dock. By 1975 all services were reported closed but with moorage still available.” In the 40+ years since this was written, nothing that he describes here even exists today.

In Our Day and Age, How Remote Is This? From the moment we head north from Sidney (at the south end of Vancouver Island) there are pockets of no cell coverage (and therefore, no WiFi access), but it doesn’t take long to learn where they are and plan for them. Over the years we’ve also outfitted Flying Colours with as much electronic equipment and long-range antennas that supposedly reach out to cell towers as far away as 40 miles (but that’s decidedly on the high side, as there are mountains in every direction, and this stuff is line of sight).

This Verizon USB-connected broadband modem is a slick little gizmo for connecting to cell towers. The data plan is pretty inexpensive, and it’s proven the best of all we’ve tried. As soon as we cross into Canadian waters I have a Telus equivalent USB broadband modem that gives us good WiFi access using a reasonably-priced data plan from this Canadian carrier.

The best piece of communications equipment we have on board is a tiny USB-connected broadband modem that plugs into a WiFi router – and as along as the broadband modem can “see” a cell tower, we have WiFi for all of our devices aboard the boat. For the time we’re in U.S. waters we have a Verizon broadband modem, and in Canadian waters we have an equivalent Telus broadband modem.

Most marinas that we moor at have WiFi coverage, and connecting to it at the dock ranges from poor or nonexistent to fairly good. The price for the WiFi is factored into the moorage charge, so if we can get internet access using it, we do. The SYC outstations all have good WiFi, assuming there aren’t a bunch of boats on the dock – and as soon as there are, the WiFi drops to zero, as every boat has a half dozen internet-connected devices on board, and there’s always someone streaming a bunch of data.

As soon as we round Cape Caution, all bets are off on whether you can get any cell or WiFi coverage, and from that perspective you feel like you’ve gone back to 1985. It’s pretty normal to go 4-5 days without access to either for the entire time. At Hakai Bay – where the Hakai Research Institute is located – our iPads and my PC are brought to shore with us each time we take Jamie for a beach walk and they allow us free access to their satellite-connected network – but they cut us off at 100MB of data transmission (which is very little). Same at Shearwater – they have a good strong cell tower nearby, and that’s good for iPads and iPhones that have cellular internet access, but for my PC I have to take it ashore to an espresso stand where they have a WiFi (at the boat, the cellular access isn’t strong enough for my iPhone or iPad to be used as a hotspot for my PC).

Once we departed Shearwater, we didn’t have cell or WiFi access until we reached Prince Rupert, which was just two days, but in normal cruising mode this could easily be a week-long trip.

So long for now. I hope to have the next leg of this cruise posted in a few short days.

Ron