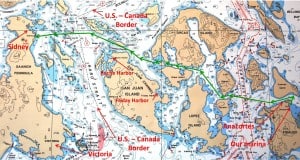

Thursday, June 14; from Anacortes Marina to Port Sidney Marina. After a marathon sprint to get everything finished for departure, we cleared our slip at 8:40AM and headed direct for Sidney, on Vancouver Island. The 49 nautical mile crossing (57 statute miles) took us just over 4½ hours – a bit

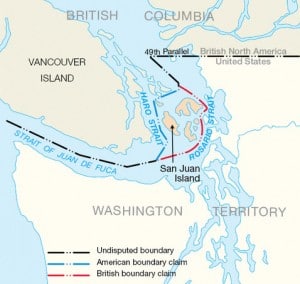

Ever wonder how some seemingly crazy international borders are created? Here’s a doozy, and it was resolved by the Pig War of 1859! In the mid-1800s, a section of the U.S./Canadian border was in dispute with the British. As you can see from the above map, the dashed line denotes the undisputed part of the border, but there’s a big jog from the Strait of Juan de Fuca up to the 49th Parallel. The Oregon Treaty of 1846 stated that this section would follow “the middle of the channel which separates the continent from Vancouver Island, and thence southerly through the middle of the said channel, and of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, to the Pacific Ocean." Well, the "said channel" wasn't clearly identified, and as the map shows two possible “channels” that could be described here – Haro Strait and Rosario Strait, with what is now the San Juan Island group in between. The British wanted it to be Rosario; the U.S. wanted Haro. It led to lots of discussion and a stand-off that lasted for 13 years. It culminated when an American farmer living on San Juan Island discovered a pig rooting in his garden – a pig that was owned by the Hudson’s Bay Company – and he shot the pig. Military intervention escalated the situation, until Washington and London negotiated a joint occupation of San Juan Island. Finally, in 1872, an arbitration committee ruled in favor of the U.S., and that’s why the border runs down the middle of Haro Strait, and the San Juan Island group is in American territory.

more than normal due to extra time clearing Canadian Customs.

Don’t forget – you can click on any photo in the post to enlarge it.

If you want to see where we are now, or better yet, monitor our route progress as we cruise along, you can go to www.ronf-flyingcolours.com and click on the Current Location link in the upper right corner of the home page.

Also, this post is more readable in the online version, plus you can read any of the posts back to 2010 from the archive – just click on the link above to the blog.

The long delay from our planned departure of May 1 gave us a bit of get-away-itis, overshadowing our plans to make the first day a proper shakedown cruise to Friday Harbor SYC outstation, where we could get our tender down for a test to ensure the leak from last summer’s incident had indeed been properly fixed (more about that in a bit).

The Guemes Island Ferry, and aptly named because it crosses the Guemes Channel between Anacortes. the 7-minute crossing is made about once an hour, carrying up to 21 cars/trucks and 99 passengers. On the Anacortes side it departs from a downtown wharf/terminal, and being completely hidden from view at its berth, when it departs it seems to appear from nowhere and reach its top speed very quickly. It's always one of our close attention factors in departing Anacortes.

Kap set a course that wound through the main east/west channels along the San Juan Islands. Starting from our marina, we headed around the north end of Fidalgo, with the Anacortes commercial shipyard on our left as we passed the downtown area. At this point we’re cruising in Guemes Channel, as the half mile wide channel separates Fidalgo and Guemes Islands. A sharp lookout is necessary to determine which side of the channel the Guemes ferry is at – it’s hidden from view until the last minute on the Anacortes side – and when it pops out as you’re approaching it has right-of-way.

As usual in transiting Thatcher Pass, we met a WSF ferry, this time the M/V Salish. In the Olympic class. The Samish is 362' long and carries 1,500 passengers and 144 vehicles, and cruises at 17 knots (20 MPH). These ferries always put up a large wake, and definitely get the attention of ZuZu, our Chief Rough-O-Meter.

Our route took us across Rosario Strait, one of the main shipping channels leading south to the Strait of Juan de Fuca (and out to the Pacific Ocean). On the west side of Rosario Strait we entered Thatcher Pass that separates Blakely Island to the north from Decatur Island on the south. Cruising up the west side of Blakely Island at our normal 8-9 knots (10 MPH), we entered Harney Channel at the southern tip of the middle leg of Orcas Island.

Just as we approached the north end of Shaw Island, the M/V Kittitas pulled out of the terminal and quickly crossed in front of us on its way into Orcas Island. Some days - like today - it seems as if the primary traffic we have to watch for is Washington State Ferries, and not only do they have the right of way, they take their right of way seriously. The Kittitas is slightly smaller, at 328', carrying 1,200 passengers and 124 vehicles, but it still puts out a significant wake that we have to be careful of.

Then it’s a left turn into Harney Channel that takes us through the passageway between the south end of Orcas Island and the north end of Shaw Island. It’s fairly narrow in places, and it’s important to keep a close watch for inter-island WSF ferries that ply between Lopez, Shaw, and Orcas Islands.

Orcas is the largest of the San Juan Island group (at 57 sq miles), but just barely noses out San Juan Island (55 sq miles). San Juan Island is more populous, at almost 7,000, whereas Orcas is around 5,000. San Juan Island has two considerable-sized marinas – Roche Harbor and Friday Harbor – with U.S. Customs clearance capability at both, and Friday Harbor boasts a lot more shopping and restaurants. Orcas, though, has the famous Rosario Resort, which is popular for weddings in a picturesque setting. Both islands have major WSF ferry terminals – Orcas has inter-island terminals that connect Shaw and Lopez Islands with Anacortes, and San Juan Island has routes to Anacortes and also to Sidney, B.C. Both islands also have frequent float plane service to Seattle on Kenmore Air.

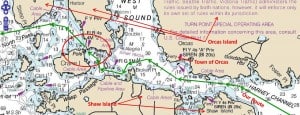

In the past few years we haven't taken this route very often, as going and coming on our summer cruise we usually make our first and last stop at the SYC outstation at Friday Harbor (and therefore cut south between Lopez and Shaw Island, rather than going into Harney Channel). After passing the small town of Orcas, then West Sound, it's imperative that we stick to our course line as there are shoals that can ground us if we aren't careful. Rather than turning left into the wider Wasp Passage, it's a shorter route to take Pole Pass, so we meander north a bit. Where it opens into a larger bay - but still quite shallow - we can see through Pole Pass and time our passage through it - as it's one boat at a time. The small village (and reasonable-sized marina) at Deer Harbor is on our right, but we again meander through the shoals to North Pass that leads into San Juan Channel.

At the western end of Harney Channel we entered the shallow (and shoaly) area leading into Pole Pass – as narrow a passage as we’ll encounter all summer – and we really have to be on our toes.

Heading into Pole Pass. Kap followed the boat that you can see directly ahead of us. The current was running against us, setting up some pretty squirrely water, so she put on extra speed. Just as she did, the sailboat on the other side (that looks like it's on the rock, but isn't) appeared. Since the pass is only wide enough for one boat at a time, the sailboat quickly turned to stop his entrance. The pass looks very calm and a straight-through shot, but there's an S-curve snaking channel that has to be followed to keep from running aground.

Pole Pass is always exciting, because it narrows down to barely 40′ wide (Flying Colours is 16′ wide), and depending on tide it’s usually just under 20′ deep at the deepest (we try not to get outside the deepest part, so our depth sounder doesn’t show just how shallow it is). A rocky shoal juts out on both sides, from the middle finger of Orcas Island on our right and the NE corner of Crane Island on our left. There’s a well-marked caution to stay under 7 knots on our approach, as anything more creates shoreline damage from the wakes. As we enter into the narrow passage the current can run quite fast, so Kap follows a smaller cruiser through the pass and picks up her speed quite rapidly. Just then, of course, we spot a sailboat that’s trying to enter from the other direction. We suddenly see the sailboat heel over as they turn sharply to terminate their passage. We scoot through without problem, and give the sailboat driver a friendly thumb’s up for his courtesy. The town and marina of Deer Harbor are straight ahead, but we follow the shallow channel out to North Pass and leading to San Juan Channel.

After Pole Pass the route curves around the north end of San Juan Island. Once past Spieden Island and you’re out in Haro Strait. Stuart Island is five miles off to our right, and at that point my pucker factor rises as we’ll soon have to check in by phone with Canadian Customs using our Nexus “trusted traveler” immigration cards and the registered boat information for Flying Colours.

At the GPS marker line on our electronic navigation charts that indicates we’re crossing the international border between the U.S. and Canada, I poked in the 800-number on my cell phone to connect with the Canadian Customs office for clearance into their waters. This is always a bit of a nail biter, as you never know what the day’s hot button will be for the Customs person (or if they’ll be in a niggly mood). Will they request endless details about the alcohol on board? Will they nickel and dime us on the type and quantity of various food stuff aboard; will they get inquisitive about shot records (particularly rabies) and food we have aboard for the cat and dog? After years of this, my standard practice is to stay calm, be extra friendly, and act as if calling in is the most natural thing in the world – and most importantly, to be prepared for anything they might ask. I keep a “boat documentation” folder in a drawer filing cabinet in the boat’s pilot house, with each page neatly plastered with Post-It notes of everything they can possible ask about – the Customs boat registration number that’s in the database for both U.S. and Canada Customs (known as the “BR” number in their parlance), our passport numbers, our Nexus card numbers, and rabies shot records for the cat and dog.

This time we got put on hold at the outset and it took a good 10 minutes for the Customs agent to come on the line. That was a good sign, as it was right at noon, and it meant agents were off at lunch, and a smaller crew was working the phones – so they’d likely want to get through us as fast as possible. When they answered, it was a female Customs agent on the line, and she sounded very congenial, which is also a good sign.

After giving her the BR number, you can tell she’s pulling us up on her screen, and it must be a record of every crossing we’ve ever made. The first question always is, “How long will you be in Canada?” On this trip it wasn’t easy question to know the best answer. If our progress north goes well we might be exiting out of Canada at the north in 3-4 weeks and entering SE Alaska. Or if we stop at Prince Rupert and then head south, our exit would likely be back here at this same spot in early September. I decided to simply say, “90 days”, and that satisfied her.

Then it’s on to “Any alcohol, tobacco, or firearms?” – and even though firearms is listed last in the question, you know straightaway that it’s the hottest button in the list – and if you have any on board it’ll be an immediate order to report at the nearest Customs port of entry. I respond no to tobacco and firearms.

One really important thing we’ve learned over the years is how to respond to the alcohol query – and that is to simply say, “Yes, we have our normal ship’s stores aboard”, and just leave it at that. To which they invariably move onto the next thing on their list, without asking any more about it. On this crossing, if they got nosy, I was prepared to say that we had 17 total bottles of spirits, for a total of just over 5 liters, plus three bottles of red and six bottles of white wine – which should not be a problem when we say “ship’s stores”. As usual, she didn’t press the issue. After that there was the usual question about the dog and cat – “are their rabies vaccinations up to date, and for the duration of time we’d be in Canada? That’s one thing we make certain to have up to date before departure.

You know they’re satisfied when they ask, “Are you ready to copy the clearance number?” – which is the all-important 11-digit number that indicates you’re now legal to enter Canada. As soon as I get off the phone I immediately update an electronic file on my PC with the number and print it out on the network printer we have on board. The paper is then Scotch taped in a salon window for any Customs person to see when/if they walk the dock (which we’ve never seen). At this point we have 15 Canadian clearance numbers on my Post-It Notes dating back to 2007 (some years we crossed in multiple times, usually for maintenance work) – and an equal number of U.S. clearance numbers for our return crossings.

Requiem for 2017. Before our cruise arrives in Sidney, let’s back up to last September to fill in some gaps. If you look at the blog archive for 2017, it ended abruptly at the top end of Vancouver Island, having just spent a night at the very scenic and interesting little marina called God’s Pocket Dive Resort. Our actual cruise continued to Labor Day Weekend and our usual stopover at the Seattle Yacht Club outstation in Friday Harbor – where we always do our end-of-summer final laundry loads of bedding and other such, plus get Flying Colours ready to go back into the slip at Anacortes. (Spending several days under cover at our marina isn’t as nice as being at Friday Harbor). Being a holiday weekend, the outstation was almost full with member boats, and when we arrived the only room left was a side tie at the end of the 120’ outside dock, which already had a 65’ boat tied up. Our stern had to stick out about 5’, which is OK (and is allowed by club rules) for being on that dock.

The Circe is a 66' classic wooden ocean racing sailboat, built in 1932 and with a storied history in the Pacific Northwest (not to mention it has beautiful lines). I guess if you're going to get "end-swiped" by another boat, one can't do better than the Circe. The owner/skipper rescued the Circe from the graveyard several years ago, and it is now available for charters on Lake Untion.

The club is about a mile from downtown, so we got the dinghy down to make a last provisioning run to town, and we had it side-tied to our swimstep at the stern. Each afternoon Kap took Jamie for a spin around in the kayak, and she kept it to the outside of the dinghy.

All was fine until our last full day at the outstation. Kap and I were inside the salon on Flying Colours when we saw a classic – and very beautiful – 66’ wooden racing sailboat passing quite close to our starboard side, obviously planning to dock at the outstation (by then a slip had opened up just across the dock from us). We watched as the sailboat turned 90° at our stern, then tried another 90° to enter the slip. With a fairly strong cross current at the dock, the Skipper didn’t make the complete turn and found his sailboat a bit diagonal to the slip and couldn’t get in. He had no choice but to back out and give it another attempt. As he backed out, the current caught him even worse, and in an instant he was backing across our stern and obviously going to sideswipe the kayak, dinghy, and then our stern. Kap and I raced out to the cockpit just as we heard a very loud crack as the kayak was pushed underwater by the sailboat’s hull – and we knew the sound was from a fracture in the kayak’s fiberglass hull. In another instant our dinghy was flipped up 90° on its side, with the outboard motor and steering console pinned onto our teak swimstep decking.

The sailboat’s Skipper – who we could see was at least 85 years old – just sat stern-faced at his helm, never said a word to any of his crew, never made a gesture, and continued to back the length of his sailboat across our stern. His totally inexperienced crew stood on deck, not knowing what to do until one of them grabbed a boat hook with a metal hook end and was using it against our fiberglass stern to fend off (and obviously gouging into our fiberglass). By now, Kap and I were out in the cockpit yelling at the Skipper to stop, but he just kept backing until he was finally clear. At that point our dinghy fell back into the water and our kayak floated to the surface. The sailboat then made a wide circle and came in properly to dock in the slip.

It was obvious we had a bit of surface damage to the stern of Flying Colours, and we were sure that the kayak’s hull had been cracked. Our dinghy appeared not to have any visible damage other than lots of skid marks where the sailboat’s hull scraped against it.

In mid-September Flying Colours was hauled at Pacific Marine boatyard in Anacortes. (At the far right, Kap - the boat's Skipper - looks pretty diminutive standing next to Flying Colours out of water.) This is the start of eight months before she's returned to the water - much longer than we'd expected.

Once docked, the sailboat’s owner came over, apologized profusely and offered up his insurance information. I immediately telephoned the insurance company in Port Townsend (where the sailboat is based) and reported the incident. I also sent an e-mail off to our insurance company so that we could get a claim started. Damn! It was the first damage we’ve had done to Flying Colours since we started cruising with her in 2009, and we were sick at heart.

We left the dinghy overnight in the water, and next morning were surprised to find about a gallon of water puddling in the steering section of the hull. It hadn’t rained, so we immediately knew there must be a breach of some kind from the sailboat incident. Using the dinghy’s bilge pump to empty out the water, we left it in the water one more night to confirm our suspicion. Sure enough, there was a gallon or two in the dinghy’s cockpit after 24 hours.

The damage to Flying Colours was mostly cosmetic, so we returned to Anacortes and arranged to have the boat hauled out in mid-September for a thorough survey inspection – which was required by the insurance company before any repairs could be started. She was taken inside a large hangar-like structure at the boatyard and a crew got to work immediately on repairing the damage. We took the opportunity to have the bottom thoroughly pressure washed, and the summer’s collection of barnacles removed from the running gear. She was then transported to the very large boatyard hangar across the street from our marina, and set down on blocks for the work to begin.

Flying Colours on blocks inside the maintenance and repair hangar at Pacific Marine. This is a huge high-bay hangar, with an overhead crain at the ceiling that can juggle boats much larger than Flying Colours around as various stages of work are completed. Behind us was a boat (Misty One) from two slips ahead of at on our dock at Anacortes Marina, completely enclosed in a plastic curtain to shield the boats around from sanding dust and painting over spray as the entire boat was refinished. There was room for at least a dozen boats in this hangar, most of them larger than Flying Colours, and most of them from the Alaska fishing fleet that returns south in the winter.

The work on Flying Colours was straightforward fiberglass repair. We had thought the boat’s trim tabs were damaged, but inspection showed nothing wrong. Some stainless steel rub rail along the swimstep and forward port side of the hull (where she was pushed into a shore power pedestal from the pull of the sailboat going past the stern. It took weeks for the rub rail material to be air freighted from Taiwan.

The conundrum was the dinghy. We searched and searched and couldn’t find anyone who was competent to work on a structure such as the fiberglass hull/rubber inflatable dinghy, even though this is by far the most commonplace type of dinghy. At first we politicked to have the dinghy declared a total loss, but then found that, unlike Flying Colours which has coverage for total replacement value, the dinghy (by insurance regulation) is only replaced at current market value. And since our purchase dates back many years, the dinghy we paid $25,000 for in 2009 now has a replacement value of around $9,000. If it was declared a total loss, we’d be out a ton of dollars – for damage that we had nothing to do with! We were incensed.

Our dinghy is 12' long, with a 40hp Yahama four-stroke outboard motor (which is too big for this dinghy, but we got talked into it). It's a fiberglass keel, and gets its flotation from the 18" diameter rubber pontoons that are laminated to the hull. The steering console is pretty nifty, with an instrument panel for speed and engine "stuff", and room for our Garmin navigation display. This is exactly how it was "side-tied" to the swim step on Flying Colours when it was scrunched by the sailboat.

Months flowed into more months, and by April Flying Colours was still in the boatyard, with the dinghy not yet repaired. Finally, after putting a lot of pressure on the yard and the insurance company to find someone who would/could work on it, they came up with a local one-person company near Anacortes that agreed to take on the job. He found and repaired a pinhole in the inflatable rib that surrounds the fiberglass hull, and it definitely was letting a small amount of water seep into the pontoon rib itself, but that didn’t explain how the water was getting into the hull. With approval from the insurance company, he peeled away the rubber rib from the hull and found that when the dinghy was flipped up onto our swimstep, it had delaminated the rib from the hull for about a foot – and that’s where the water was coming in. He stripped the pontoon rib completely away from the hull, cleaned it all up, then re-bonded it back, completing the repair. After that, Flying Colours was back in the water by mid-April – but with all of the normal preparation work still to be done, it was too late for our long-planned early May departure to SE Alaska.

Our new favorite place to dine in Sidney, the Stonehouse Pub, located in Canoe Cove on the outskirts of Sidney and around the corner from the B.C. ferry terminal at Schwartz Bay. Our favorites here are Sambuca Prawns sautéed in butter, and apple smoked BBQ ribs for a main dish.sauteed in butter

Back to 2018 – Arrival in Sidney, June 14th. With so much time lost, we decided to make our stopover in Sidney as short as possible. We normally spend a week, but this time we cut it to three days, getting all of our fresh vegetables and potted plants purchased, plus the obligatory dinner and lunch at our favorite restaurant, the Stonehouse Pub at Canoe Cove just outside Sidney. They have some of the best BBQ ribs we’ve found anywhere. Our friends, Steve and Andrea Clark on the Couverden (a Fleming 55 just like ours) graciously offered to let us use their slip at Port Sidney Marina, as they were heading off to meet up with some friends from the Lopez Island Yacht Club who were rendezvousing at Port Browning in the Canadian Gulf Islands. Our plan was to meet up with them in a few d days for our venture north. We both still hope to get as far as SE Alaska, and we’ll cruise together as much as possible.

On the night before our departure Kap likes to get her engine room checks out of the way. This is part of her Skipper duties, and something she takes very seriously, and it's surprising how often she comes up with something of concern that needs to be tended to. The checks include water in the bilge, oil leaks anywhere around the main engines, transmission, shafts, and generator. Very important is a check of several "sea strainers" - large glass/plastic see-through containers that have a filter for the sea water that's brought in for various functions - cooling the engines, and input salt water to the watermaker.

Sunday, June 17; Port Sidney Marina to Ovens Island . . . no . . . to Silva Bay Marina. When we’re cruising, Kap spends a huge amount of time listening on the VHF radio for the weather reports, and watching her favorite internet weather sites for marine weather in the area(s) we’ll be cruising. The big unknown was weather and seas out on the 25-mile wide Strait of Georgia that we’d have to cross, between Vancouver Island and the Canada mainland (the best route to work our way north). The most important part of that unknown is the timing of the slack tides through one of several passages between the Canadian Gulf Islands that open onto the Strait of Georgia.

Our route takes us around the top end of the Saanich Peninsula (that Sidney is located on), with a not-so-wide passage past the B.C. ferry terminal at Schwartz Bay. The ferry in the terminal here is the Spirit of British Columbia, half again the size of the largest Washington State Ferry - at 548' long - and can carry 2,100 passengers and 358 vehicles at 20 knots (23 MPH). The route for these big guys is to Tsawwassen (pronounced "tuh-wass-en") for passengers between Vancouver and Victoria (at the south end of Vancouver Island). As we go by, it's imperative that we watch for the ferry's departure, as it's sudden and generally unannounced - and they pick up speed very rapidly.

Sunday looked like our best day to depart, and the decision was made to head for Ovens Island to spend the first night at the Seattle Yacht Club outstation at the privately owned island, then early the next morning (Monday) wind through the long island chains of the Gulf Islands to Gabriola Island Passage where we could catch the slack tide at around 1PM.

Our route from Sidney this time is one of my favorites – around the north end of the Saanich Peninsula, past the Schwartz Bay B.C. Ferry terminal, and then north through the picturesque passageway that separates Saltspring Island from the east coast of Vancouver Island. It’s the shortest route to Ovens Islands, but more often we cruise up or down on the east side of Saltspring Island because we like to stop in at the small town and port of Ganges (where Kap gets her favorite gelato cake and we always have a wonderful dinner at Auntie Pesto’s Café).

Our route takes us between the east coast of Vancouver Island and the west coast of Saltspring Island. Saltspring Island, at 74 sq miles, is half again the size of San Juan or Orcas Islands. It's noted for artists, vineyards, and expat Americans who headed for Canada during the Vietnam War.

Since our cruise to Ovens Island was around 30 miles we weren’t in a hurry and cruised along at 8 knots. Some days the current can run a bit fast through Sansum Narrows, but it’s not one that requires you wait for slack. We had about 1 knot against us, and dropping us down to 7 knots over the ground wasn’t a problem. We enjoyed the cruise.

As we entered Stuart Channel, and about 10 miles still to go to Ovens Island, Kap re-checked our time against the slack time for Gabriola Passage that leads onto the Strait of Georgia at the south end of Gabriola Island. Figuring we could safely pass through up to an hour before slack, she realized that if we slowed down a bit (to 7 knots) we could head directly for Gabriola Passage and overnight at Silva Bay Marina on the SE corner of the island. We always like Ovens Island, because it’s free moorage at an SYC outstation and we have the island all to ourselves if no one else is at the dock. By contrast, Silva Bay is a commercial marina that will cost around C$100 for the night. But I’m OK with it either way. Also, it would get us onto the Strait of Georgia three hours earlier for the next day’s trip across, and that’s even better.

This is the size of a typical lumber mill along the B.C. coast. To give a reference, that's an ocean-going freighter at the lower left, and the tiny red/tan "humps" in the water at the right are huge barges (300' long) ready for towing and carrying sawdust for particle board.

Using their online website, I made a reservation at Silva Bay Marina, and we altered course. At 1:40PM, after dawdling around to kill some time, Kap headed us into Gabriola Passage and we got safely through with no problems at all.

Shortly after arrival at Silva Bay Marina a text message came through from Couverden that they too were heading for Silva Bay, and about three hours later they arrived. The wind was really whipping up on their arrival, and blowing crosswise to their boat and the dock it took several of us to help them get secured with their lines. (Kap and I are both still spooked – maybe even traumatized – by a passage through here last year, when we decided to transit ahead of slack and the whirlpools were so strong, and caught us off guard so quickly, that Flying Colours was almost 90° to the courseline (in a very narrow and shallow channel) in a second. Kap slammed the throttles forward and whirled the wheel around, and we got righted again before we ran aground. It’s probably the closest we’ve come to serious problem in a squirrely passage.

And how does a mill like this get its log input? Mostly by barges towed by tug (which seems catawampus here because it was making a right turn ahead of the barge). The barge being loaded so stern heavy is unusual, but they obviously had a reason for it.

We were advised when we radioed in on VHF Channel 66A that the restaurant and liquor store had burned over the winter (Kap later read that this is the third time in about 30 years that it’s burned, which seems fishy). It wasn’t a problem for us, as we planned to eat on the boat. We also learned they had a small boat fishing derby going on, and as we arrived they were just handing out the prizes for the biggest fish catches – which I think was a 20 lb salmon.

Kap, Steve, and Andrea met in the evening on Couverden to discuss the next day’s planned crossing of the Strait of Georgia. The weather looked good, the winds were supposed to die down early in the morning, and seas were expected to be light. We went to bed thinking it would be a good crossing.

Monday, June 18; Silva Bay Marina to SYC Garden Bay Outstation. At 6AM, after a final discussion with Couverden it was decided to depart at 6:30. All was calm inside the secluded Silva Bay, with light winds and glassy smooth water. Fifteen minutes later, though, all hell broke loose as we moved out into the Strait of Georgia. The wind hadn’t yet died down – still blowing at almost 20 knots, and the seas were angry with 5’-6’ waves hitting us head on. Kap set the throttle for 8 knots, figuring we didn’t want to beat the boat apart, much less have a seasick (and throwing up) cat and dog on board. She tried crabbing to the left, then to the right to see if she could find a sweet spot that wasn’t too bad. Couverden, taking a different tack, increased their speed and they later reported that it helped a lot in ride quality, but probably wasn’t the greatest in fuel burn.

Throughout the first couple of hours, every fifth or sixth wave group just about buried our bow, sending spray over the top of the boat. We knew it would be encrusted with salt spray on arrival at Garden Bay, and weren’t looking forward to the cleanup.

Our route crossed the SE corner of Whiskey Gulf, the Canadian/U.S. submarine underwater torpedo firing range, and our VHF radio weather channel indicated it was “Not Active” today, which means it’s clear to enter it. You never know until the day of crossing whether it’s going to be active or not, and you’re always hoping it won’t be. Having to skirt well around the perimeter adds miles and at least an hour to the crossing. When it’s active the area bristles with Navy patrol ships on the surface, and at the first sign their radar picks up of someone violating the space, the on-shore Navy control base is on the radio with orders to move away – and the patrol boats are on you like stink to give you some trouble.

The biggest worry, though, is always floating logs. Recently there had been some very high spring tides, which were high enough to pull stranded logs off the beaches. You’d think that in a body of water 25 miles wide and 50 miles long that the chances of hitting a log would be very small. Not so. In our first half hour out I was at the helm and I suddenly spotted a 25’ long log – a full 18” in diameter – floating crosswise in our path ahead, not more than a boat length away. I instinctively hit the autopilot button to put the steering on manual and seeing that we were heading for the right half of the log, I cranked the wheel around to starboard, barely missing the log by a couple of feet. Couverden was following behind us at the time, so Kap radioed the information as a caution to them and they responded that they could see the log from several hundred yards behind us.

As soon as the seas calmed ZuZu was at her favorite cruising spot - stretched out full between the pilot house windscreen and dashboard, soaking up the sun.

Three and a half hours later we were finally in the lee of Texada Island (pronounced “tex – aid’-a) and things calmed down. By now, Couverden was at least a half hour ahead of us. At four hours into the day’s cruise we entered Pender Harbour on the Canadian mainland. The SYC outstation is at the deepest part of the harbor, in a small bay tucked away from all other traffic. Rather than being jammed full of member boats, the docks were empty except for the Couverden, and Steve and Andrea came over to our dock to catch our lines and get us secured. We’d basically have the whole place to ourselves. A month from now – after the 4th of July – this place will be filled up, and additional boats anchored nearby waiting for any boats to leave. We’d prefer solitude, so that’s another reason we like getting here early and late in the cruising season.

A nostalgic note. When Kap and I were traveling so much in the 1980s and 1990s, there were several domestic and international cities that almost felt like home to us – even though Clyde Hill is really home – cities like New York, San Francisco, Sydney, Auckland, Singapore, London, Munich, and Amsterdam. After visiting places along the Inside Passage – such as Garden Bay and a dozen more – 20+ times (coming and going) in the past 11 years – they too feel like home when we arrive. It’s a nice feeling . . .

And an epilogue note. The day after our arrival at Garden Bay, we lowered the dinghy to the water – primarily to head across the bay to the small town of Madiera Park to an IGA store where we can get some extra provisions. Within seconds of the dinghy settling onto the water we noticed there was water rising in the floor, sparking immediate fears that the repair wasn’t successful. Remember – we had set off a week earlier and bypassed our shakedown cruise to Friday Harbor to check that all was OK, and now we were farther north than we’d have liked if we had to turn back for home to complete repairs. Kap jumped in as I raised it in the air enough to drain, and she quickly spotted that the “bung plug” was not seated properly – the bane of all small boat boater’s, who take the bung plug out over the winter and forget to put it back in next spring. In our case, we’ve never taken the plug out, but the guy who did the repair did and then didn’t put it all the way in. Once that was corrected, we determined the dinghy was now keeping out the water. Almost every year we vow to do one or two short shakedown cruises before we head off on the summer’s main cruise, but something always gets in the way and we run out of time.