Where Am I Going With This Title? In 1945, an American first-time author, Betty McDonald, wrote a humorous biography about her experiences as a newlywed trying to run a chicken farm near Chimacum on Washington State’s Olympic Peninsula. The book was widely (and wildly) popular, although she raised the ire of several Chimicum residents who thought they were being unjustly skewered in the book.

Soon (1947), a wildly successful movie of the same name was released starring Claudette Colbert as Betty McDonald and Fred MacMurray as her husband, with Margorie Main and Percy Kilbride as her hillbilly neighbors, Ma and Pa Kettle. Later that year, Colbert and MacMurray did a radio version of the film that was broadcast on the Lux Radio Theatre.

To illustrate the popularity of this genre, Universal Studios highlighted the most outlandish of the characters in a 1949 movie titled Ma and Pa Kettle, again starring Marjorie Main and Percy Kilbride. This spawned an incredible nine sequels (yes, there were sequels even in those days) – throughout the 1950s (the last being in 1957). The real life characters of Ma and Pa Kettle from Chimicum sued the author for defamation of character, but lost the suit when husband showed up at a nearby county fair with a chicken under his arm and a sign identifying him as Pa Kettle. (And the whole concept was still kicking around when the stupid Beverly Hillbillies TV series began it’s 10-year run in 1962.)

Egg Island is the mounded bit of land that fills this photo. To the north of it is False Egg Island. I haven’t a clue why either island is named as it is, but I’m sure there is a good little story behind each. Egg Island has an Environment Canada weather station on it – all lighthouses and weather stations on the B.C. coast seem to be white buildings with red roofs. Presumably, the tower near the high point of the island transmits weather data that is then broadcast via Canada Weather VHF channel 1.

Where Was I Going With That Information? In our story at hand, after we rounded Cape Caution a few days ago we passed by an island that we hear weather reports from every day on the Canada Weather VHF radio channel – Egg Island. Although it’s hundreds of miles away from the Betty McDonald story, I can’t help thinking about it every time I hear a weather report. Now, just north of Cape Caution we get to see a real Egg Island. Corny, huh?

If you want to see where we are now, or better yet, monitor our route progress as we cruise along, you can go to www.ronf-flyingcolours.com and click on the Current Location link in the upper right corner of the home page. Also, this post is more readable in the online version, plus you can read any of the posts back to 2010 from the archive – just click on the link above to the blog. And don’t forget – you can click on any photo in the post to enlarge it.

SE Alaska or Explore the Central B.C. Coast? The big question now is, being the 10th year since we cruised to SE Alaska in our 42’ Nordic Tug, COSMO PLACE, what should we do this year to commemorate it? On that first trip this far north, we crossed into SE Alaska on June 13th and cleared Customs in Ketchikan that afternoon – our 19th day away from Anacortes. For this year’s cruise, today (July 28, sitting in Shearwater) marks our 38th day, and if we decided to head for SE, we’d still be at least five days out from crossing the border.

For the past several days, we’ve kicked around thoughts of going as far north as Prince Rupert – the northernmost coastal city in British Columbia, and the jumping-off point to Dixon Entrance that would take us to Ketchikan. It was tempting, and we both had a hankering to be in Prince Rupert again. But in the end we concluded that we’d probably have a better time staying near the area we’re at right now (the Central B.C. coast) and explore places we bypassed in a hurry 10 years ago. We are definitely learning how to take it easy, spend a day or two longer in each anchorage, and cut our cruising speed when we’re on the go to no more than 9 knots.

Heading For Cape Caution (July 18th). Neither of us have fond memories at Port Hardy due to past experiences (located about 20 miles north of Port McNeill, and considered to be the primary jumping-off point for heading north across Cape Caution).

In 2008, we were real greenhorns about how marinas work in these parts, not knowing when or how far in advance we needed to get moorage reservations along the cruise route. We arrived at Port Hardy without a reservation for the Quarterdeck Marina – the only commercial marina in the harbour – and we managed to get the last bit of available moorage space, a side-tie on the end of a dock with small finger piers for private fishing boats (we were traveling with our new-found friends, Bucky and Christy on UNDOC’D, and by chance they had earlier made a reservation). The marina’s lady harbor master was none too friendly, and she told us we could stay two days and no longer, and since that was all we were interested in, we said OK. But before the two days were up Kap learned from the VHF Environment Canada weather reports that we were in for a blow, and we really should stay put. The harbor master, though, would have none of that, as she had another boat with a reservation scheduled for our moorage spot and she told us we had to go. We protested, but to no avail. Since Port Hardy is at the northern tip of Vancouver Island, we had no place to go – so with UNDOC’D we headed across Queen Charlotte Sound and into the really nasty weather towards Cape Caution.

This year, our visit to Port Hardy was completely unplanned, as we’d just spent three days on the other side of Queen Charlotte Strait anchored out at Blunden Harbour, with the expectations of heading directly north from there, and around Cape Caution at the first sign of good weather. On our last morning at Blunden, though, our dinghy outboard motor acted up as we were taking Jamie ashore – stalling out, sputtering, coughing up a lot of blue smoke – and acting as if we had some serious internal problems. This was no time to be heading into days and days of remote anchoring on the other side of Cape Caution, so discretion told us to head for Port Hardy and possible motor repairs.

Once secure in Port Hardy, though, we were flatly turned down by the Yamaha outboard motor shop (we have a Yamaha motor) because they were totally booked up for two weeks of work. And we got nothing but a runaround from the other shop. Incredibly, we couldn’t even duplicate the problem with the motor, leaving us concerned that we had an intermittent-only problem. After four days on the dock, plus a couple of trips to the grocery to finish out our provisions, we decided to get out of Dodge. Our second visit to Port Hardy has now convinced us – if we can help it – that we never need to see this place again during our cruising days.

Most of you reading this know that I'm not much of a seafood guy - but this lingcod that I cooked up for dinner was absolutely wonderful. It was pan fried to get a crisp outer coating, then finished in the oven and served with a ginger citrus sauce.

For some reason, bottom fish are the ugliest creatures in the ocean - but they are actually some of the best tasting fish (think cod for fish and chips). This guy pictured here is a lingcod, and it's what we ate after a dock mate gave us a big slab of very freshly-caught lingcod.

The one good thing to come out of our stay at Port Hardy was a large slab of very fresh lingcod, just caught that morning, that a woman on the boat across the dock offered to us. We’ve never knowingly eaten lingcod (other than in restaurant fish and chips), and if I saw one of these prehistoric-looking creatures in the flesh I’d probably not want to ever eat one. We were assured it was similar in flavor and texture to halibut – maybe not quite as flaky when cooked – but delicious no matter how you cook it. Already having dinner underway for the evening, we gratefully accepted it and put it in the fridge for the next evening. In the meantime I consulted my favorite onboard cookbook for that type of dish – Alaskan Rock’n Galley, by LaDonna Gundersen (wife of commercial fishing captain Ole Gundersen, of SE Alaska), and it had a recipe for Ginger-Citrus Rock Cod that sounded really good, and I figured it would be good with lingcod too. Just dipped in flour, pan fried first to get the brown exterior, then finished in the oven, and served with a wonderful ginger-citrus vinaigrette spooned on. It was absolutely delicious and we had it again a second night just to make sure I’d gotten it right (remember, I’m not much of a seafood eater, so to say this is going a long ways.

This chart shows our route around Cape Caution, the westernmost mainland point of Canada, and one of the two open Pacific Ocean stretches along the Inside Passage. The weather is always the big bugaboo here, and it's wise to pay close attention to what's brewing up for winds and waves in this area. The Egg Island weather reporting station for Environment Canada is at the top end of the chart section.

As our Port Hardy departure neared, the weather forecast was so-so, but Kap felt we could make it across the Queen Charlotte Strait, duck into Allison Harbour, and anchor in a sheltered spot to wait for weather before making our attempt to get past Cape Caution.

The further we got across Queen Charlotte Strait, though, the better the weather and seas were, and abeam of Allison Harbour we decided to press on around Cape Caution. We could definitely feel the 3’ rollers that were coming in from the great expanse of the Pacific, plus a 1-2’ chop that was caused by a bit of wind – but overall, the cruise past Cape Caution was what it should be . . . a non-event.

The Western Towboat Company towboat, Ocean Titan, heading south at Cape Caution. The tug’s distinctive blue, yellow, and white markings make it easy to spot. The barge is probably stacked 6-7 high with containers.

Just before Egg Island (a weather reporting station for this area), we met a Western Towboat and barge, heading south and about a mile further offshore than us. Given the day of the week it could have been our old friend Cap’n Doug Meyers on the Pacific Titan (the towboat that I went to SE Alaska in 2003, and both Kap and I went in 2005). We hailed on Channel 16 and learned that it was the Western Titan, a sister towboat.

At around noon we rounded Cape Caution, our first time since 2008 when we went to SE Alaska. It seems like a major milestone in our cruising, as it’s one of the two bugaboo spots if you’re heading to SE (the other is Dixon Entrance, a wide expanse between Prince Rupert on the Canadian side, and Ketchikan on the U.S. side). It’s one of the two sections of the Inside Passage that aren’t in protected waters of the island chains off the British Columbia mainland, and anyone with an ounce of brains doesn’t attempt it unless the weather conditions are good. Unfortunately, there isn’t anything scenic about Cape Caution – to stay in safe seas it’s best to leave 2-3 miles between you and the shoreline, and it’s one area where there aren’t any rugged fjord-like mountains in site – just a low coastline, and it’s only from your nautical charts that you can see the accomplishment.

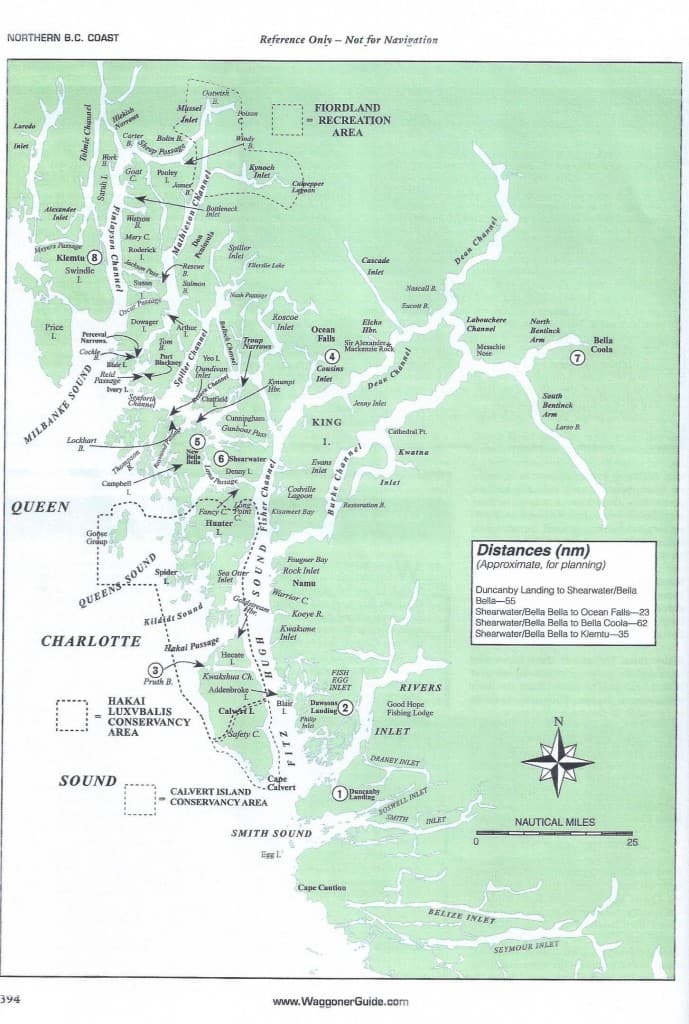

Caption for map: The above is a good overall map of where we’ve been since mid-July when we rounded Cape Caution (located near the bottom of the map). Fury Cove is on the west side of the island group above the circled #1. Pruth Bay (#3) is at the north end of Calvert Island. Lizzie Cove is just to the west of Fancy Cove, at the top of Hunter Island. Shearwater and New Bella Bella (#6) are north of that. Gunboat Passage is just above Shearwater. Ocean Falls (#4) is up Fisher Channel and at the end of Cousins Inlet. Codville Lagoon is just to the right of where you see Fisher Channel. And as I write this, we’re at Dawsons Landing (#2), getting ready to head south past Cape Caution tomorrow (8/5). Not far beyond Cape Caution is the basis for my blog post title – our cruise past Egg Island. This is the site of an Environment Canada weather station, and it’s one of the two or three that are most significant for determining the conditions to round Cape Caution. Kap listens to VHF weather reports multiple times each day, and the frequency for this region always broadcasts Egg Island conditions. For some unknown reason, every time I hear Egg Island mentioned on the radio I think of the book, The Egg and I (it’s like one of those worm songs that, once it gets into your head, you can’t get rid of it).

Fury Cove, on the SW corner of Penrose Island, just north of Rivers Inlet. It has a rather trcky entrance, first to an outer lagoon that’s named Unprotected Anchorage – and we assume it’s aptly named. Once inside that, you turn left through a narrow opening to Fury Cove. We anchored just inside the opening.

These two beach photos create a panorama of the wide "midden" area of Fury Cove. Tucked in the trees, nearly unseen, is an old derelict structure that is identified in our guide as a kayaker's hideaway (but very well may date from much earlier times).

Two of the three largest beaches inside Fury Cove – all midden beaches. On a sunny day, and if you didn’t know better, you might think you’re on a beach in Hawaii or the Caribbean. They were perfect spots to take Jamie twice a day to do ”her bidness”. The small white spec in the center is across Fitz Hugh Channel on the outside, and it’s the very large Alaskan ferry, Malaspina, that runs weekly from Seattle to SE Alaska.

Fury Cove. Within an hour of passing Cape Caution we were at the opening to Fury Cove – and our first-ever visit there. The entrance into the cove (or, really, a lagoon) is fairly tricky, but our cruising guides provide pretty detailed instructions on which side of that rock you should pass on, the course heading to make the passage, and even where the best anchorages (and safest for holding power) are located. There were five or six boats already at anchor, so we motored around for a few minutes and then selected what we thought was the best remaining spot. Judging from how the anchor set, it appeared to be a mud bottom, which is great for holding. Within an hour or two, a stream of boats continued to arrive, until there were 16 boats anchored. At least another 10 could have gotten in if necessary.

The amazing part of this lagoon was the almost-white beaches scattered around – three large ones at the west side of the cove, where the terrain was almost at high tide level, and from Flying Colours we would look past them to the open water outside the cove. Another three beaches were scattered around the cove.

The beaches were all middens – remnants of a long ago time when First Nations people lived here in villages, and broken shellfish shells from hundreds of years of harvesting the shores for food. It’s hard to believe how many shellfish it takes to creates entire beaches like this. (Caption: here’s a closer shot of the beach, showing just how extensive the broken shells are.

Pruth Bay has been the long time home of a fishing camp, but a few years ago the non-profit Hakai Institute purchased it and converted it to a research station. To get there, we turned left (west) off Fits Hugh Sound at the top end of Calvert Island and followed the relatively narrow channel to the 3-point bay at the western end. When we departed three days later, we went north, then through Hakai Passage to return to Fitz Hugh Sound.

For scale reference, the overland distance from the head of Pruth Bay west to the Pacific Ocean Beach is ¼ mile. The grey land strip that surrounds the beach is the greatest sand you’ll see this side of Hawaii.

This photo, taken from our anchorage, looks like a fresh water lakeshore anywhere in the world, but it’s actually at the head of Pruth Bay, showing the Kakai Institute on shore.

Fury Cove to Pruth Harbour. After leaving Fury Cove, we crossed Fitz Hugh Sound to get in the protection of Calvert Island, then followed its coastline north. Calvert is a big rugged island, with steep shorelines that rise 100’-200’ from the water’s edge – and it appears to be uninhabited. The west side of it fronts directly onto the Pacific Ocean, with the 6-mile wide Fitz Hugh Sound to the east. Fitz Hugh is a main channel of the Inside Passage, extending 50 miles to the north, with long channels branching off to the NE from it (Rivers Inlet was the first, just before we got to Fury Cove).

At the top end of Calvert Island (and along Fitz Hugh Sound) is a long finger of water leading westward that separates Calvert from the smaller Hecate Island that was obviously combined with Calvert eons ago. The passage going in to the west is a First Nations name, Kwakshua Channel, and while it looks fairly narrow on the accompanying chart, it’s probably ½ mile wide in most places, and it’s several miles deep.

We’d heard about Pruth Bay several weeks earlier when we were at the SYC Garden Bay outstation – a fellow club member had just spent some time there, and he told us it was an absolutely wonderful place to anchor, with good access to the beach for Jamie, and a ¼ mile long trail that would take us over to a fantastic Pacific Ocean beach. We decided to give it a try, as we’d never heard of it before.

From a long ways out we could already see about 10 boats anchored in Pruth Bay. We tend not to squeeze through boats already at an anchorage, so we dropped our anchor a sufficient distance behind the outermost boat, which made it about a ¼ mile dinghy ride to shore.

Hakai Institute. After being on the hook (at anchor) in remote places left us with a need to get either cell phone or WiFi access – something that would attach us back to the outside world. That something was Pruth Bay, with its Hakai Institute on the shore. According to a posted sign on the dock, “Hakai Institute is “a research, teaching & leadership center serving the BC Central Coast”. Their research focuses on “long term ecological” factors that affect the BC coastal area, particularly “where the Pacific Ocean meets the temperate rainforest, the channels, inlets, estuaries and watersheds”. Their scope is the 15,000 years since the end of the last Ice Age, and particularly “includes analysis of the extensive human habitation of this area during that time”. The institute is funded by the Tula Foundation, a BC-based private foundation that was established by a private couple from Vancouver (obviously with a strong social agenda, plus a lot of money). The focus is to bring in a couple dozen science major graduate students from Canadian universities on a grant and part-time work basis, and have them work alongside full-time researchers on projects. As I write this, we’re at Dawsons Landing, and the couple who own it told us their daughter graduated from university last year and she’s now doing a yearlong sabbatical at Hakai Institure.

This could be a wide expansive beach on Waikiki if it wasn't for the evergreen trees in the background. Granted, this photo was taken at about mid-tide, but even at high tide the water only came up to about where Kap is standing.

Behind the institute buildings is a boardwalk trail that leads ¼ mile directly west, opening onto an incredible Pacific Ocean sandy beach. After walking the beach for a while, we picked up a trail at the southern end that leads over a small ridge and to another, smaller and more secluded beach. On our return, Kap let Jamie off the lead, and she just ran . . . and ran . . . and ran her little heart out on the sandy beach. Then she discovered a flock of sandpipers grouped on the beach, and she chased them from one end of the beach to the other. Her running stamina was just incredible, and it never occurred to her that they were faster and more aerobatic than her, and that she’d never be able to actually catch them. It just didn’t matter to her – it was running for sheer pleasure.

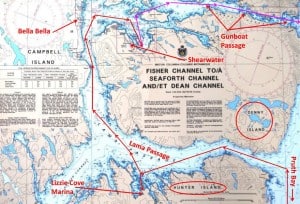

This chart shows our route towards Lizzie Cove on Lama Passage, then north to our 4-day Shearwater anchorage, then up and through Gunboat Passage on our way to Ocean Falls.

Pruth Bay to Lizzie Cove Marina. After two nights at Pruth Bay, Kap was feeling “boxed in” for some reason and I could tell she wanted to get underway. It was foggy when we first headed to shore with Jamie around 7AM, then started raining just as we returned to Flying Colours a few minutes later.

Rather than return to Fitz Hugh Sound the way we came, Kap headed us north on a tricky little passage taking us to Hakai Passage on the top end of Hecate Island (she calculated this would save us about 10 miles). Once we were back on the expansive (6-mile wide) Fitz Hugh Sound, the cruise northward to the Lama Passage turnoff was about three hours (around 30 miles).

Funny little flashback story to tell. On the way south in the Nordic Tug in 2008, cruising in heavy fog one early morning after leaving Shearwater, we met the Western Towboat Pacific Titan just after turning onto Fitz Hugh Sound from Lama Passage. We were probably ¼ mile apart, having a chat on VHF channel 68, when Cap’n Doug gave us a blast on his ship’s horn – and it was loud! Without missing a beat, Kap picked up the radio mic and responded, “Hold on tight and protect your ears . . . here’s a blast from Cosmo Place” – at which she tooted what sounded like a toy sound you get with a little rubber squeeze horn. We all had a good laugh. We’re pleased that the horn on Flying Colours is quite close to that of the Pacific Titan, and actually makes you jump whenever we give it a blast.

Canadian Coast Guard cutter named the Captain Goodard – this is what the “law” on the water looks like in this part of the world. We met on the Lama Channel on the way into Lizzie Cove.

Less than a mile after meeting the Coast Guard cutter, we hailed Lizzie Cove Marina on VHF for instructions on winding through the treacherous rock, shoal, and islet hazards at the entrance to the cove. Our cruising guide indicated it involved passing three tiny islets on our port side, then a sharp turn to the right, keeping a red bouy on our starboard and a following green bouy on our port side, staying away from the shoal that extends a long way out from such-and-such island, and then go deep into the cove to where we’ll see the totally deserted single dock of Lizzie Cove Marina. All of this was in very shallow water, so we wanted to make certain that what we saw out our windows was exactly what the guide described.

This helter-skelter collection of house and dock floats makes up the Lizzie Cove Marina. It’s easily the most ramshackle marina we’ve seen anywhere on this coast – as close to Ma & Pa Kettle as it could be (you have to know 1950s movies to pick up on that reference). Note the whale rib above the Happy Hour area in the near building.

Lizzie Cove Marina. Once tied up on the dock, we readily saw that the foursome who run Lizzie Cove Marina (three women and a man – all mid-70-ish) are as friendly as they come, and the stopover was worth it. Besides, from a telephone call to Shearwater Marina – our next stop – we’d already learned their docks were totally full with cruisers heading south from SE Alaska. We couldn’t get in until at least the following day. Confirming that, as we approached the turnoff from Fisher Channel to Lama Passage, we could hear VHF radio traffic with Shearwater and everyone was being directed to a no-charge and no-power catch-as-catch-can breakwater dock outside of the marina. We had a tentative reservation for the following night, so we decided to give Lizzie Cove Marina a try. It too is no-power, no-water, and not quite free, but just the sheer novelty of it makes it worthwhile.

From the bow of Flying Colours, it’s hard to tell what’s what with the collection of buildings an floats. Although we were tied to a dock, this is as close to anchoring out as it gets. In the photo, the little grass area to the left of the blue whatzit is the dog pee patch, so that’s a lot more convenient than ferrying Jamie ashore in the dinghy twice a day.)

This entire marina was relocated in September, 2014 to Lizzie Cove in a single towing trip from Namu Bay – 10 miles away and across Fitz Hugh Sound, where this crew had run their marina for many years and catered to cruisers heading north to Ocean Falls. On moving day, they lashed their entire marina operation together in a single, snaking float, 1,000’ long by 125’ wide. It must have been amazing to watch, particularly towing through the snaky S-turns around the shoal areas at the entrance we’d just come through. Oh, and Kap noticed the whale rib that’s mounted above the front door. Inside that open room are picnic tables, where Happy Hour could be held when it there are lots of boats on the docks (which we don’t think happens anymore).

Next morning, when we ventured into the building cluster to pay for our moorage, we were invited to visit their greenhouse float – and it was amazing. About 25’ x 25’ square, surrounded and covered in greenhouse glass, it was full of several peach trees (bearing lots of fruit), a fig tree or two, an apple tree (grafted from five different varieties), dozens of tomato plants, and a huge variety of herbs. Like virtually all other marinas within fifty miles, all electrical power comes from a diesel-fueled generator, and with the greenhouse to supply several versions of food, they are pretty much off the grid.

An old, derelict fish processing cannery at the entrance to Shearwater Harbour. The entire B.C. coast was dotted with these canneries in the first half of the 20th century, but these fallen-down old relics are all that’s left of this local industry.

The fishing industry is still here, but here you can see a seiner pulling directly up to a floating loading at Port McNeill and offloading. A suction tube is inserted into the seiner's fiish hold, the salmon are shot out through the tube that you can see running past the concrete pier column. From there they are sorted into plastic tubs, then loaded with a fork lift into the semi truck on the dock. We see three or four seiners a day when we're in Port McNeill, and this must happen all up and down the coast.

Shearwater Marina, with the derelict-looking dock/breakwater out in front. This photo was taken from Flying Colours at anchor, having never moved from First Place on the main dock waitlist for moorage. Note the white Nordic Tug 42, Golden Hour, at the left on the breakwater – I’ll mention it in a bit when we get to Codville Lagoon.

Lizzie Cove Marina to Shearwater Marina. Our cruise from Lizzie Cove to Shearwater was a quick one hour. All the way there, we tried to raise the harbor master on VHF, but with no luck (we didn’t know until later that he doesn’t get to the dock office or answer the radio until 9AM). No matter – the guy is a totally worthless specimen of a human (my opinion only), running the marina dock like a little fiefdom, and if you refer to him by his name (Kristof) on the radio, he figures you’re his friend and he creates a space on the dock. We didn’t know his name, so we were relegated to anchoring offshore to await our turn on his infamous “waitlist” – from which we were never called after four days of waiting (I was in need of going to the hospital in nearby Bella Bella to have a horse fly bite tended to – which I eventually did, and it was treated with antibiotics, as it caused my eyes to swell shut). Kap sees the situation differently, but since this is my blog, it’s my opinion that I’m stating. Of all the places we cruise to each summer, Shearwater Marina is one that I’d like to never see again, but unfortunately, it’s a virtual “must-stop” on both the north and south passage in this area.

Shearwater to Ocean Falls – via Gunboat Passage.

At the end of our frustration with the goon-on-the-dock at Shearwater Marina, we finally made up our mind where to go next (up to now, we hadn’t decided if we’d continue to SE Alaska, just go as far as Prince Rupert and turn around, go halfway to Prince Rupert (to a First Nations village called Kelmto where we toured a longhouse in 2008), or explore the local area a lot more). After hours and hours of discussion, we finally decided on the last idea (explore the local area), starting with Ocean Falls, about 40 miles to the NE of our present position.

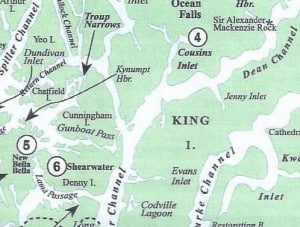

Gunboat Passage is navigable, but tricky in a few places. The problem is shoaling – where it’s shallow for relatively long distances off visible shore, and typically impossible to know if you’re going to run aground without a bow watch, which would reduce speed to dead slow. Thanks to the commercial fishing boat ahead, our electronic chart plotter that we can zoom in on, and in the trickiest place, a pair of range markers that you can visually sight on, the passage was safely negotiated.

Our best (most interesting and scenic) route to get there was Gunboat Passage, beginning directly off the north shore of Shearwater harbour. After verifying with a couple of nearby cruisers that Gunboat was an appropriate passage for a boat our size, we brought up our anchor after four days at Shearwater and were ready to depart. Interestingly, our anchorage was just offshore from a log skidding area (and where logs were corralled into booms to be towed to the nearest sawmill). As I was bringing up the last 50’ of anchor chain, the links were wrapped with bark strings from the water’s bottom – obviously, a lot of stripped-off bark had settled on the bottom, and dragging the anchor chain through it caused a bunch of it to catch on our chain links. We have a high-pressure chain wash on the bow sprit to wash off bottom mud that comes up with the chain, plus I always have a high pressure hose in hand to make sure the chain is clean before going down into the boat’s chain locker – but it isn’t prepared to handle long strips of cedar bark that’s intertwined with the chain links. Every few feet, I’d have to stop the windlass to clean out the bark and throw it overboard. What I couldn’t get to, though, was a bunch of bark that was stripped off and wrapped around the windlass rollers at the bow sprit – and it stayed there for the next month until we could get it cleaned up in Port McNeill (where I’m finishing up this post).

Already assuming that Gunboat Passage was going to be tricky, Kap was wishing we’d find another cruiser that we could tag along behind (and hopefully it wasn’t the first time for them too) and they’d know how to best avoid the shoals and rocks in the narrow, shallow areas. Better yet, we slotted our entrance to the west end of the passage behind a commercial fisherman, and he was going the exact right speed for us to safely follow.

This photo is the near range marker. As we approached it a ½ mile earlier from the channel in front of it, we could see the far range marker above it – and when the black line lined up between the two, it indicated we are on the right course within the channel.

(This explanation refers to the accompanying Gunboat Passage chart, showing the near and far range markers and the shoal areas.) The first section of the passage (moving east – and on the left side of the chart) was pretty straightforward – we just slowly followed the fishing boat. But as we progressed down the first red line, the near range mark came into view. Using binoculars, I kept the black line on the yellow sign aligned between the two, by giving Kap instructions to “steer to port” or “steer to starboard”. On the chart, you can see the light blue areas pointed to by the arrows, indicating shoaling areas – inside which we’d run aground if we didn’t stay in the channel indicated by the range markers. (This is serious business. Just last month, a friend of ours sailing around the world in their 45’ sailboat had the boat sink off an island in French Polynesia after they ran aground on an uncharted shoal, creating enough structural damage to their boat that it took on water. They were luckily rescued by a nearby boat that they managed to get to with their dinghy.)

Fisher Channel and Cousins Inlet, looking north towards Ocean Falls – numbered 4. Our route over the previous week had taken us west on Lama Passage to Lizzie Bay Marina, then past New Bella Bella and into Shearwater – numbered 5 and 6. After several days at Shearwater we cruised through Gunboat Passage and back out to Fisher Channel, up Cousins Inlet, to Ocean Falls.

Beyond the nearest ridge line at the water’s edge on the right is a Y-fork to Dean Inlet. Continuing straight transitions into Cousins Inlet and Ocean Falls is at the foot of the mountain in the far background.

This is our view of Ocean Falls as we approached in Flying Colours. What you see here is all that remains of Ocean Falls. The tiny marina is at the left, and we moored directly across the dock from the sailboat. Behind the marina is a very large, also very ramshackle and huge 2-story shed that housed the various workshops that supported the mill (as near as we could tell, the mill itself was destroyed, as we saw no evidence of it).

It was a calm, warm, peaceful cruise, and the scenery was absolutely spectacular. The mountains along the route rose directly out of the water, with ridge after ridge receding into the background. We hardly saw a single boat along the way, and it was like being in our private paradise.

In the photo, Ocean Falls is at the foot of the tall mountain in the far background, but you can’t see the remnants of the ghost town until you turn a sharp 90° bend at the very end of Cousins Inlet, and then barely a mile away is a very sad reminder of the town that used to be.

Photo taken from a platform at the edge of a still-working marine ways (at the lower left) that hauls boats into the shed for repairs. Flying Colours can be seen at the far end of the dock furthest out from the shore.

The really nice guy who runs the Ocean Falls Marina carved the quite good mermaid statue on the beach at the end of the marina dock. My guess is, he was inspired by the famous Little Mermaid carving outside the marina in Copenhagen, Denmark.

A derelict, shuttered 400-room hotel is in the right half of the photo. As near as we could tell, the only operating business in town was a fishing lodge, but it too was closed at the time of our visit, and it may now be closed for good. Other than the sheer beauty of the cruise in and out, we can’t see any reason for a return visit.) In the early 1900s, Ocean Falls boasted a population of around 3,900, with a large number of them employed at a bustling paper mill that was powered by a hydroelectric dam at the edge of town. Strangely enough, there wasn’t sufficient logging in the area to supply the mill and it suffered economic problems for decades, finally going bankrupt in 1976. To save the town and industry, the B.C. provincial government purchased the mill and tried for another 10 years to keep it open, but in 1986 finally threw in the towel and closed it down. Inexplicably, the government then tried to bulldoze the entire town into oblivion – and almost succeeded, until a handful of remaining residents put up such a protest that it was stopped when just a handful of buildings remained.

The dam directly behind the town of Ocean Falls is quite impressive. The spillway is probably 500’ wide, and the hydroelectric generator in it powers a large part of the nearby region. It’s very unusual to see power lines lining the water’s edge, but a single string runs south from Ocean Falls.

During our overnight stay, Kap and I toured (endured is a better word) a tour of a “relic” museum, occupying the entire second floor of the work shed at the head of the dock. One of the town’s handful of residents, known as Nearly Normal Norman – an 86-year old gentleman who arrived on the scene in 1986, just as the town was shutting down for good – took to collecting flotsam and jetsam for his museum from every nook and cranny of the town – bottles, signs, you-name-it. For a small donation, Nearly Normal Norman gives guided tours of his museum, and it lasts as long as you can stand it. Afterwards, Kap and I took an hour long stroll through the completely boarded-up town, then walked up a gravel road behind town to see the “falls” that gave Ocean Falls its original reason for existence.

Ocean Falls to Codville Lagoon. Kap was concerned about a weather system that was closing in, and we decided after one night at Ocean Falls to Codville Lagoon. It was an uneventful cruise of four hours, and by early afternoon we were comfortably anchored in this very scenic lagoon.

But rather than get to that next part of the cruise, I’m going to stop here and get it posted. I’ve been writing on this post for upwards of a month now, but we haven’t been in good enough cell/WiFi coverage to upload it. We’re just heading out of Port McNeill this morning and back into the wilds for a week or so, so I’m going to wrap this up. It hasn’t had the final two or three edit reviews that I’m used to, so there may be more grammar and logic errors than I’d like. I’ll just have to clean it up later for the copy that stays for posterity.

Ron