This Flying Colours post will be an unusual one – with very little mentioned about Flying Colours. Instead, it will be all about cruising for two weeks on a boat several feet longer than Flying Colours, but only half the width – called a “narrowboat”. Our cruise is on the Llangollen Canal in the English Midlands and NE Wales with our longtime friends, Tom and Linda Dixon from Boise.

(Remember, you can click on any photo to enlarge. Also don’t forget that the formatting of this blog post is better – everything lines up better – when you can read it online at www.ronf-flyingcolours.com – click on this link to go there. Also, if you’re logged into the post with your own userid, you can request an automatic update whenever a new blog post is put up – just click on the Subscribe link and enter your e-mail address. You cannot do this, though, if you’re logged in using the “friends” username.)

First, how did this unusual cruise come about? Well, way back in February I posed the question to Tom during one of our catch-up e-mail threads – “I don’t suppose you and Linda would like to try a narrowboat canal trip on some idyllic English countryside canal this fall, would you?” The next day Tom wrote back that they were interested, and that got the research going.

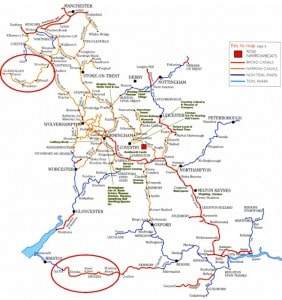

When you do an internet search on “U.K. narrowboat canal holidays” the number of hits is just overwhelming. Before you can even sift through the myriad boat hire companies, you first have to get an idea of which canal you want to cruise, and in which part of the U.K. There are 2,200 miles of navigable canals that are linked into a giant network extending throughout England and Wales – as you can see from the map at left. Where to begin the research????

When you do an internet search on “U.K. narrowboat canal holidays” the number of hits is just overwhelming. Before you can even sift through the myriad boat hire companies, you first have to get an idea of which canal you want to cruise, and in which part of the U.K. There are 2,200 miles of navigable canals that are linked into a giant network extending throughout England and Wales – as you can see from the map at left. Where to begin the research????

First – what is a narrowboat, and how did these amazing canals come about?

The U.K. canals pre-date railroads and car/trucks, and for three hundred years the canals and the barges that plied them were the freight haulers of the day. For whatever reason – most likely the cost of canal digging and construction, plus geography – the canals throughout the U.K. are quite narrow in many places . . . sometimes as narrow as 7’ . . . and the locks, tunnels, brick road bridges, and lift bridges are barely more than 7’ wide. As a result, the towed canal barges were typically 6’-6” in width – and hence the name, narrowboat. They were long, though, as long as 70’ in overall length, with all canal side structures capable of handling boats up to this length. Additionally, the canals were rather shallow – as shallow as 3’ – so the narrowboat hulls were designed with an 18” draft.

Second, in the early days the canals were mostly plied by barges that were towed by horse, donkey/mule, or pit ponies (so named because they were bred to pull carts in underground coal mines). When steam and diesel engines came into use, some of the towed barges were replaced (but not all – Kap and I toured a canal museum just outside Liverpool, and a couple who lived their entire lives on a freight-hauling barge still used a mule right up to their retirement in 1957).

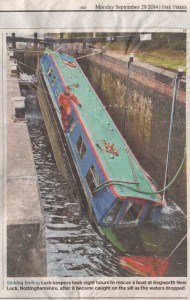

By the 1950s, many of the canals began to fall into serious disrepair as a result of railway and truck freight. England and Wales are still crisscrossed by thousands of miles of derelict canals, but luckily, about 2,000 miles have been restored to use for leisure cruising, thanks to the amazing work of the U.K. charity organization, the Canal & River Trust. As the photo at left shows, it isn’t just a matter of dredging out a muck-filled canal and running water through it again – but rather, includes restoration of “an enormous network of bridges, embankments, towpaths, aqueducts, docks and reservoirs alongside everything else that makes up our wonderful waterways.” The amazing part of this is, the result not only establishes a connection with a long-ago way of life that is hard to even imagine in today’s modern world, but it creates an incredible way for everyday people to enjoy it with self-drive holidays on these narrowboats.

By the 1950s, many of the canals began to fall into serious disrepair as a result of railway and truck freight. England and Wales are still crisscrossed by thousands of miles of derelict canals, but luckily, about 2,000 miles have been restored to use for leisure cruising, thanks to the amazing work of the U.K. charity organization, the Canal & River Trust. As the photo at left shows, it isn’t just a matter of dredging out a muck-filled canal and running water through it again – but rather, includes restoration of “an enormous network of bridges, embankments, towpaths, aqueducts, docks and reservoirs alongside everything else that makes up our wonderful waterways.” The amazing part of this is, the result not only establishes a connection with a long-ago way of life that is hard to even imagine in today’s modern world, but it creates an incredible way for everyday people to enjoy it with self-drive holidays on these narrowboats.

But back to our trip planning. Early on I stumbled onto a web site for the Kennet and Avon Canal (shown by the red circle at the bottom of the map above), described as “one of the loveliest waterways in Britain … meandering 86 miles between Bristol and Reading, passing through the historic city of Bath”. It intrigued me, as we’d be due west of London (close proximity to our arrival/departure at London’s Heathrow). And having never been to Bath, I thought it would be an interesting end point to explore. I poured over the online brochure and its description of possible cruise distances, mostly considering two week trips without a daunting number of locks. (Kap and I were on a 7-day French canal boat cruise in 2009 – on the Canal du Midi in Southern France – and except for a full day’s stop in Carcassonne to see the medieval fortress city, the 60+ locks completely dominated our cruise days. I was determined not to make that mistake again.) After lots of analysis and e-mail discussion with Tom and Linda, a “flight” of 29 stair step locks – called the Caen Hill Locks, that we’d have to do twice on this out-and-return cruise – nixed that canal choice from consideration, eating up two full days just on these locks. (Stair step locks are necessary where there is a larger-than-normal elevation change, and back-to-back locks “step” the canal boats up or down approximately 7’ in each lock. The elevation change at Caen Hill must be about 300’.)

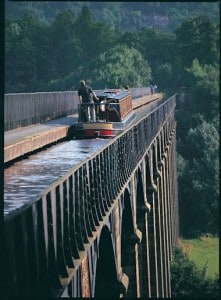

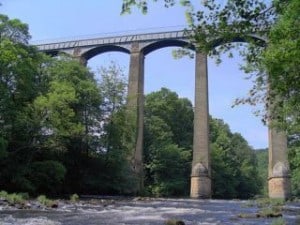

Then I spotted a link to the odd-sounding LLangollen Canal in Wales (at http://www.canalholidays.com/llangollen-canal.htm), starting with the description “considered the most beautiful waterway in the country . . . includes the famous Pontcysyllte Aqueduct, one of the wonders of the canals” – and a World Heritage Site. In a leisurely 54 mile out-and-return cruise, we’d have 12 locks in each direction, including three stair step locks. The description of the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct was what convinced me this was the canal for us – on approach to the Welsh mountains near our turnaround point at the small town of Llangollen, we’d cross a wide valley of the River Dee 126’ below us, in a cast iron trough just the width of the boat, supported by graceful stone and masonry piers. Coupled with the quarter mile long Chirk Tunnel (1,381’ to be exact), plus myriad bridges to pass through, I was quickly convinced this canal merited further research. Tom and Linda agreed.

Then I spotted a link to the odd-sounding LLangollen Canal in Wales (at http://www.canalholidays.com/llangollen-canal.htm), starting with the description “considered the most beautiful waterway in the country . . . includes the famous Pontcysyllte Aqueduct, one of the wonders of the canals” – and a World Heritage Site. In a leisurely 54 mile out-and-return cruise, we’d have 12 locks in each direction, including three stair step locks. The description of the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct was what convinced me this was the canal for us – on approach to the Welsh mountains near our turnaround point at the small town of Llangollen, we’d cross a wide valley of the River Dee 126’ below us, in a cast iron trough just the width of the boat, supported by graceful stone and masonry piers. Coupled with the quarter mile long Chirk Tunnel (1,381’ to be exact), plus myriad bridges to pass through, I was quickly convinced this canal merited further research. Tom and Linda agreed.

I next studied the Blue Waters Holidays website for boat bases, quickly settling on their Base 19 near the market town of Nantwich, in the English county of Cheshire and the old Roman city of Chester (straddling the Wales/England border, this cruise would wind in and out between the two U.K. countries multiple times).

![]() Next task was boat selection. With two couples in such tight quarters for two weeks, I felt that maximum space was best and settled on the Ashton Class boat – 66’ long, full galley with dinette, two cabins with either two singles or one double each, two toilets, and two showers. Again, Tom and Linda agreed on this, and we settled on a layout with a double bed cabin for them and Kap and I chose two twin singles, as we’d learned from the France cruise that a double was too small (little did we know just how small a narrowboat can really be).

Next task was boat selection. With two couples in such tight quarters for two weeks, I felt that maximum space was best and settled on the Ashton Class boat – 66’ long, full galley with dinette, two cabins with either two singles or one double each, two toilets, and two showers. Again, Tom and Linda agreed on this, and we settled on a layout with a double bed cabin for them and Kap and I chose two twin singles, as we’d learned from the France cruise that a double was too small (little did we know just how small a narrowboat can really be).

Once the basics were decided, the rest was just details – paying a deposit on the cruise, booking trans-Atlantic flights, car rental to get to/from LHR and the canal base, and the necessary hotel rooms before and after the actual cruise. And, of course, digging through as much literature as we could find on how to actually do a U.K. canal cruise, including daily cruise plans, where we’d eat, and such mundane things.

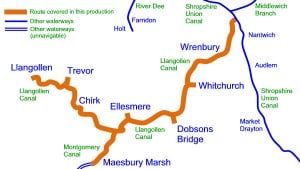

So, just where is the Llangollen Canal? Well, in the big picture, it’s on the NW border of England and NE border of Wales, just below

Liverpool and Manchester. On the Google Map, the canal (not marked) is in the lower left quadrant, and you can locate Liverpool and Manchester to the north. In the large scale map that shows the canal in orange, our plan was to cruise out-and-return on the section from the tiny village of Wrenbury at the upper right, to Llangollen at the upper left (with a side trip on the Montgomery Canal to Maesbury Marsh at the bottom.

Liverpool and Manchester. On the Google Map, the canal (not marked) is in the lower left quadrant, and you can locate Liverpool and Manchester to the north. In the large scale map that shows the canal in orange, our plan was to cruise out-and-return on the section from the tiny village of Wrenbury at the upper right, to Llangollen at the upper left (with a side trip on the Montgomery Canal to Maesbury Marsh at the bottom.

Tuesday, September 16, 2014, Across The Pond. Given that my United Airlines frequent flyer account has a gazillion miles in it, we decided to fly First Class to London. There are several route options, and we chose Seattle (SEA) – San Francisco (SFO) – London (LHR) in both directions, with B757 service between SEA and SFO, then B777 service on the Trans-Atlantic segments.

Our SEA to SFO flight, with an 8:30AM departure and 10:50AM arrival, gave us a first. On deplaning at SFO, we were met at the aircraft cabin door by a UAL representative holding a name board that had my name and Kap’s name written out on it. My heart sank, as it instantly spelled trouble of some kind.

“What’s up,” I asked. “Something wrong?”

“No, nothing wrong . . . I have a Mercedes waiting below to take you to your London flight,” she responded.

At that, we descended the outside stairs from the jetway and onto the tarmac below. Twenty feet away was a large Mercedes SUV with a livery uniformed driver waiting at the back to stow our hand baggage. Once inside, our UAL lady guide introduced herself as a United Global Services representative, and she was taking us directly across to our waiting aircraft – but since we had plenty of connection time she’d first take us to the Global First Class lounge.

It’s not every day one gets to weave through commercial jetliners sitting at their gates. Since we were heading for the international terminal, there were two or three B747 tails that we drove under, another two or three B777 tails, and one brand spanking new United B787 Dreamliner (that’s it at left).

It’s not every day one gets to weave through commercial jetliners sitting at their gates. Since we were heading for the international terminal, there were two or three B747 tails that we drove under, another two or three B777 tails, and one brand spanking new United B787 Dreamliner (that’s it at left).

The best part of this was, getting from the United domestic terminal to their international departure gates typically requires passing again through TSA security, which is still a hassle even though we’re part of the TSA Pre-Check program (the fast-access program that has short lines, no requirement for 3 oz liquid containers to be in a Ziploc bag, and laptops stay in your carry-on). So, with that service, and within 10 minutes of getting off our SEA-SFO flight, we were comfortably seated in the United Global First Class Lounge just a few feet from our London departure gate. What a deal!

International First Class is always a pleasure, ensconced in what United calls their Global First Suites – a complicated affair that’s large and thoroughly outfitted with every comfort (you push a button on the center console and as the seat bottom slides all the way forward, the seat back lays down to make into a 6’3” flat bed) . Nevertheless, it was a long, overnight flight, with a very so-so dinner served shortly after take-off, and an even more so-so warmed-over breakfast served just before landing. In between was a fitful night of sleep, but it was still better than in the seats in the back of the airplane.

International First Class is always a pleasure, ensconced in what United calls their Global First Suites – a complicated affair that’s large and thoroughly outfitted with every comfort (you push a button on the center console and as the seat bottom slides all the way forward, the seat back lays down to make into a 6’3” flat bed) . Nevertheless, it was a long, overnight flight, with a very so-so dinner served shortly after take-off, and an even more so-so warmed-over breakfast served just before landing. In between was a fitful night of sleep, but it was still better than in the seats in the back of the airplane.

Our arrival at LHR was on time at 7AM, and Kap and I were the first two passengers off the plane. It always seems like a mile’s walk to Passport Control, winding down this walkway, then another, then up this escalator, down another one, and finally into the huge Passport Control hall.

Our arrival at LHR was on time at 7AM, and Kap and I were the first two passengers off the plane. It always seems like a mile’s walk to Passport Control, winding down this walkway, then another, then up this escalator, down another one, and finally into the huge Passport Control hall.

One huge advantage to First or Business Class is getting a Fast Track card to use at Passport Control on arrival, where Kap and I were second in line (as opposed to being 200th in line as in the sample image at left that I grabbed from the internet), getting us to the baggage area within a few minutes of deplaning. By 7:30AM, we were through the formalities and standing in line for the morning’s first latte at a Café Nero coffee counter in the newly renovated Terminal 2 (until earlier this year, United had used Terminal 3 since it bought the Pan Am London routes many years ago – and being brand new, this was a welcome change).

With a latte in hand, we headed straight for the nearest cell phone kiosk in the terminal (due to excessive roaming rates, almost every European traveler buys a cell phone or SIM card the moment they arrive in London). My hope was to purchase a U.K. SIM card that could give us WiFi access through my Telus broadband gizmo that I’d purchased a couple of months earlier in Sidney (B.C.) and used aboard Flying Colours (that would have a data plan much cheaper than with either a U.S. or Canadian SIM card). We quickly located a kiosk, but unfortunately, the young woman working it was totally unknowledgeable about what I needed and directed us to their other kiosk in Terminal 1. It was a long hoof, pushing a heavy luggage cart through the subterranean walkways of the LHR terminals, but we got there alive and well. Sure enough, the guy knew what I wanted, and within a half hour he configured it for me and we were on our way. As you can see in the photo, the gizmo is about ½ the size of a bar of soap, and attaches to my PC with a USB cable. (I hoped it would be a communications lifesaver for us on the canal boat, but it wasn’t – after trying it several times on the first two days on the boat and getting nowhere, it went into my suitcase and never saw the light of day again.)

With a latte in hand, we headed straight for the nearest cell phone kiosk in the terminal (due to excessive roaming rates, almost every European traveler buys a cell phone or SIM card the moment they arrive in London). My hope was to purchase a U.K. SIM card that could give us WiFi access through my Telus broadband gizmo that I’d purchased a couple of months earlier in Sidney (B.C.) and used aboard Flying Colours (that would have a data plan much cheaper than with either a U.S. or Canadian SIM card). We quickly located a kiosk, but unfortunately, the young woman working it was totally unknowledgeable about what I needed and directed us to their other kiosk in Terminal 1. It was a long hoof, pushing a heavy luggage cart through the subterranean walkways of the LHR terminals, but we got there alive and well. Sure enough, the guy knew what I wanted, and within a half hour he configured it for me and we were on our way. As you can see in the photo, the gizmo is about ½ the size of a bar of soap, and attaches to my PC with a USB cable. (I hoped it would be a communications lifesaver for us on the canal boat, but it wasn’t – after trying it several times on the first two days on the boat and getting nowhere, it went into my suitcase and never saw the light of day again.)

Next stop was a rental car pickup along the airport perimeter road. For flexibility I had rented from Europcar, booking it for the full two-week duration of our canal cruise, with the plan to drive it to the canal departure point, leave it there during our cruise, then drive it back to London at the cruise end. We have lots of experience driving right-hand cars on the left side of the road, so it was no problem – but our rule is, the person not driving is always alert to ensure the driver doesn’t do something stupid (like pull out of a parking lot and automatically head for the wrong side of the road). For that, Kap has a good rule – the steering wheel side of the car is always next to the center lane, so that mantra helps keep us out of trouble.

GPS. One more pre-arrival detail to mention. Our trusty Magellan Roadmate GPS that saved our bacon on several earlier European trips was big and bulky, and getting long in the tooth compared to today’s handheld units. We kicked around the idea of just using the Google Maps road directions on my iPhone or our iPads (we have Kap’s iPad Air and my iPad mini with us), but experience has shown that any lapse in cell coverage wipes out your turn-by-turn directions. We opted to get a small Garmin car GPS before we left home, purchased the U.K. maps to download, and it’s worked beautifully on the trip. One of the best new features with it is specific lane guidance, which has paid for itself many times over on motorway interchanges and complex roundabouts.

Pre-canal cruise time in Chester. The 3-hour drive from LHR to Chester was hectic and tiring, mainly due to very heavy traffic, and a surprising amount of road construction. I had booked a 3-night room for us at the Chester Hilton Doubletree Hotel on the eastern side of Chester. We’ve never been to Chester before, and frankly, knew absolutely nothing about this city of 328,000 people (to be honest, I thought it was a city of maybe 50,000 at most). As we soon learned, Chester is an old walled Roman fortress city, founded in the year 79, making it almost 2,000 years old! It was part of the Roman Empire for three hundred years, and to this day is one of the best-preserved walled cities in Britain. (I snapped the photo above from our sidewalk dining table on Chester’s walking street, first amazed that the building housing the restaurant was built in 1274, but then even more amazed when it dawned on me that the city was already well over 1,000 years old at the time this was built.)

Pre-canal cruise time in Chester. The 3-hour drive from LHR to Chester was hectic and tiring, mainly due to very heavy traffic, and a surprising amount of road construction. I had booked a 3-night room for us at the Chester Hilton Doubletree Hotel on the eastern side of Chester. We’ve never been to Chester before, and frankly, knew absolutely nothing about this city of 328,000 people (to be honest, I thought it was a city of maybe 50,000 at most). As we soon learned, Chester is an old walled Roman fortress city, founded in the year 79, making it almost 2,000 years old! It was part of the Roman Empire for three hundred years, and to this day is one of the best-preserved walled cities in Britain. (I snapped the photo above from our sidewalk dining table on Chester’s walking street, first amazed that the building housing the restaurant was built in 1274, but then even more amazed when it dawned on me that the city was already well over 1,000 years old at the time this was built.)

As usual, Kap poured over the various tourist books we had with us, and the next day we set out to visit the National Waterways Museum at Ellesmere Port on the south side of Liverpool. Since we’d be boarding our canal narrowboat in two days’ time, the combination indoor/outdoor museum that incorporated real working canal locks with examples of canal barges in operation was very interesting. Even though we watched as a canal boat was being taken through three stair step locks, we didn’t have a clue what we were looking at or how they operated.

Later in the day, Kap steered us to another engineering wonder of the canal days – the Anderton Boat Lift – a five-story tall iron spider-looking thing, built in 1875, and created to raise canal boats 50’ from the River Weaver to the Trent & Mersey Canal. The lift was in continuous operation until 1983 when structural deficiencies were detected. A restoration to correct the problems was completed in 2002, and the boat lift now operates only to give a lift up and down 3-times a day to a tourist boat.

Later in the day, Kap steered us to another engineering wonder of the canal days – the Anderton Boat Lift – a five-story tall iron spider-looking thing, built in 1875, and created to raise canal boats 50’ from the River Weaver to the Trent & Mersey Canal. The lift was in continuous operation until 1983 when structural deficiencies were detected. A restoration to correct the problems was completed in 2002, and the boat lift now operates only to give a lift up and down 3-times a day to a tourist boat.

In the photo at left, I’m obviously standing at the bottom of the lift, with the River Mersey passing behind me (the water leading into the lift is a small arm from the river to the lift). On either side of the tall circular column is a canal boat “tub”, each one holding a single narrowboat. The tubs act as counterweights, raising one boat in one tub as it’s lowering another boat in the opposite tub, so there would always be one tub at the top and one at the bottom. When ready to lift/lower two narrowboat barges filled with goods, a small amount of water in the lower tub is drained, and the higher weight of the upper tub lowers it as it raises the other.  In the next photo I’m standing on a grassy berm, at eye level with the upper canal. Just inside the white fence is an aqueduct that a narrowboat drives into or out of to the Trent & Mersey Canal to the right of where I’m standing.

In the next photo I’m standing on a grassy berm, at eye level with the upper canal. Just inside the white fence is an aqueduct that a narrowboat drives into or out of to the Trent & Mersey Canal to the right of where I’m standing.

While exceedingly complicated by the engineering standards of the day, the use of a lifting mechanism eliminated the need for 7-8 stair step locks, plus the resulting water loss (there wasn’t a good source of nearby water to serve the locks).

And you might be asking, what was the great industrial or economic purpose of canals in this area that warranted such incredible feats of engineering, and at such cost? The answer: salt. The following is quoted from the Wikipedia article on the Anderton Boat Lift: “Salt has been extracted from rock salt beds underneath the Cheshire Plain since Roman times. By the end of the 17th century a major salt mining industry had developed around the Cheshire “salt towns” of Northwich, Middlewich, Nantwich and Winsford.” (The “wich” suffix in these Cheshire town names means they are associated with salt, which we learned while having lunch in Nantwich and I asked the shopkeeper about it. A more complete discussion of it can be found in the Wikipedia article on “-wich towns”, at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/-wich_town.)

Speaking of Nantwich, on the day we first met up with Tom and Linda we had lunch in the town square. While perusing a very nice deli to see if it had anything we might need on the narrowboat, I spied an item on the shelf that is uniquely British – and fitting for the country that invented the indoor flush toilet – a roll of toilet paper branded by the very man who is thought to have invented the WC – one Thomas Crapper. Whether the invention claim is valid or not, he was a plumber in London who founded the company, Thomas Crapper & Co, and with his invention of the ballcock, he did indeed make the flush toilet considerably more popular.

Speaking of Nantwich, on the day we first met up with Tom and Linda we had lunch in the town square. While perusing a very nice deli to see if it had anything we might need on the narrowboat, I spied an item on the shelf that is uniquely British – and fitting for the country that invented the indoor flush toilet – a roll of toilet paper branded by the very man who is thought to have invented the WC – one Thomas Crapper. Whether the invention claim is valid or not, he was a plumber in London who founded the company, Thomas Crapper & Co, and with his invention of the ballcock, he did indeed make the flush toilet considerably more popular.

Saturday, September 20th, 2014 – Narrowboat Pickup Day. The big event for the day is to have a quick look at our narrowboat “home” for the next two weeks, and then head to the nearest supermarket for some provisioning.

Our boat base is in the tiny village of Wrenbury Mill, about five miles SW of Nantwich (and about 30 miles SE of Chester). Not as old as Chester, but nevertheless listed in the Domesday Book (completed in 1086), with a population of 1,100. It boasts two pubs, a convenience store that carries food stuffs similar to what you’d find in a 7-Eleven, a 500 year old Anglican Church, a post office, a doctor’s surgery, and of course the Alvechurch Boat Centre.

When we arrived, our boat wasn’t yet returned from the current renters, but we got a glimpse of what it would look like – from her Aston class sister boat, the Bean Goose, sitting at the dock. We couldn’t board her to have a look around as the next hire group was readying to depart, but we got a good briefing of our accommodations – enough for us to set off provisioning. We also got to see just how long 66’ is, and it definitely gave us pause.

When we arrived, our boat wasn’t yet returned from the current renters, but we got a glimpse of what it would look like – from her Aston class sister boat, the Bean Goose, sitting at the dock. We couldn’t board her to have a look around as the next hire group was readying to depart, but we got a good briefing of our accommodations – enough for us to set off provisioning. We also got to see just how long 66’ is, and it definitely gave us pause.

A main part of our plan was not to cook any more meals on board than absolutely necessary, particularly evening meals – but rather, to eat at local pubs whenever possible, and to get off the boat as often as possible to explore the countryside and nearby villages. This was to be a leisure holiday, leaving day-to-day chores like cooking at home. We’d have breakfast on the boat, but mostly just cereals, toast, and yoghurt with berries. For lunch, we’d stock up on sandwich fixings and instant soups.

At 4PM we returned with a half dozen shopping bags and our luggage, ready to board our now-ready Yellow Legged Gull awaiting us at the dock. After everything was loaded, we were ready for our boat briefing and we’d be off.

At 4PM we returned with a half dozen shopping bags and our luggage, ready to board our now-ready Yellow Legged Gull awaiting us at the dock. After everything was loaded, we were ready for our boat briefing and we’d be off.

The briefing was from bow to stern, including how to fill fresh water tanks (recommended every day at filling points found along the canals), how/where/when to pump out the black water tanks (one for each head, and we eventually pumped out twice during our two week cruise), how to operate the diesel heating system, cautions on what not to put down the electric toilets (“nothing that we haven’t eaten”), all about operation of the boat’s diesel engine, and instructions on how the tiller/rudder works. It all took a bit less than an hour . . . and we were ready to go.

We also had a shore briefing of important things along our canal route – particularly how to operate the locks. Our first lock was at least five miles down the canal from our begin point, and in all likelihood we’d be alone to operate it. The boat hire place had a small scale model (about 3’ in length, shown at left) of a typical lock, and we got about a 10 minute briefing on how to open and close the lock doors, raise and lower the water level, and the various “rules of the road” concerning who has right of way when two boats approach the lock from opposite directions, and how to leave the lock if you see someone approaching as we depart. The concepts were all easy enough, but I must confess that many of the details of the actual lock mechanisms weren’t clear to me. Luckily, Kap took charge of our first lock, and that’s good, as her spatial and mechanical abilities are superb.

We also had a shore briefing of important things along our canal route – particularly how to operate the locks. Our first lock was at least five miles down the canal from our begin point, and in all likelihood we’d be alone to operate it. The boat hire place had a small scale model (about 3’ in length, shown at left) of a typical lock, and we got about a 10 minute briefing on how to open and close the lock doors, raise and lower the water level, and the various “rules of the road” concerning who has right of way when two boats approach the lock from opposite directions, and how to leave the lock if you see someone approaching as we depart. The concepts were all easy enough, but I must confess that many of the details of the actual lock mechanisms weren’t clear to me. Luckily, Kap took charge of our first lock, and that’s good, as her spatial and mechanical abilities are superb.

When we were ready to go, our boat yard mechanic steered the boat out of the basin, as it required a tricky 90° to enter the canal, then to head immediately through the narrow confines of a lift bridge – and that was definitely beyond our skill level to start with. Once through the bridge, the tiller was handed over to Kap, as she was designated to be our first Captain of the cruise. She drove well enough that the mechanic hopped off on the shore within a ¼ mile, and we were on our own. Kap stayed at the tiller until our first night’s stop – and managed not to hit anything or sink us.

Given the late hour of our departure (5PM), we didn’t have a long cruise planned for this first day . . . but hopefully far enough down the canal to get the hang of things, and maybe tie up along the bank near the first pub we came to.

Given the late hour of our departure (5PM), we didn’t have a long cruise planned for this first day . . . but hopefully far enough down the canal to get the hang of things, and maybe tie up along the bank near the first pub we came to.

Our pub guide identified the first pub as The Swan Inn, in the tiny village of Marbury, and supposedly ½ mile walk up the Hollyhurst Road from the bridge where we’d left the boat (it was, in fact, easily a mile). The pub notes mentioned, “This classic old English farmhouse pub, licensed as far back as the 1750’s, is now an excellent destination food house, retaining traditional public house atmosphere, in the centre of the beautiful village of Marbury, right on the village green.” It was our first taste of pub food for this trip, and it certainly wasn’t our last.

Our pub guide identified the first pub as The Swan Inn, in the tiny village of Marbury, and supposedly ½ mile walk up the Hollyhurst Road from the bridge where we’d left the boat (it was, in fact, easily a mile). The pub notes mentioned, “This classic old English farmhouse pub, licensed as far back as the 1750’s, is now an excellent destination food house, retaining traditional public house atmosphere, in the centre of the beautiful village of Marbury, right on the village green.” It was our first taste of pub food for this trip, and it certainly wasn’t our last.

Eating in pubs. English pubs bear a bit of description. Throughout the U.K., the concept of restaurants is very different than in America. Most towns and villages, particularly the smaller ones, don’t have restaurants as we think of them (i.e., nothing like a T.G.I. Friday’s, or a Red Robin; no McDonalds, no KFC, no Subway, nothing whatsoever like that). Instead, even a village of 50 people will have a pub, and many very small towns will have two pubs. The Swan Inn pictured above is a very common style of pub – with a second floor that has two or three rooms for the overnight traveler, a proper bar with at least a half dozen beer pulls, a back bar for spirits, and ample tables for dining in adjoining rooms. If you’re at the pub for dinner, standard procedure in most places is to first find a table, then go to the bar to order a pint of beer or glass of wine, taking a menu back to the table with you. Once the menu is consulted, you then go back to the bar to order (and pay in advance), pointing out where your table is (or give them the table number). The food is then brought to you when it’s ready. More and more pubs now have a wait staff to take your order at the table, possibly because that’s how it’s done in the movies or they’ve seen it in other countries.

Pub food is quite standard, and typically includes all of the English favorites – steak and ale pie, sausage and mash in a Yorkshire pudding, fish and chips, gammon (ham steak) with fries and peas, and one or two cuts of steak with peppercorn sauce or other sauce. The food is usually OK, but not top notch, and after a few days of various pubs it becomes monotonous and you yearn for the variety of American restaurants. We never once saw some of the more famous British oddities, such as Toad In The Hole, Spotted Dick, or Bubble & Squeak.

Our first night on the Yellow Legged Gull. Dinner at the local pub always took longer than we expected, and walking back to the boat every night was in the dark. This first night, we were lucky that everyone had a flashlight (or headlamp) of some kind, as the pub was more like a mile from the boat, it was a dark, overcast night, and the lane to the canal had lots of animal manure about.

Needless to say, the first night was a miserable sleep for both Kap and I. Our single beds were on opposite sides of our tiny stateroom (if you can call it that, and it was also the hallway between Tom and Linda’s stateroom and the rest of the boat). Our mattresses were broken-down affairs, and I spent most of the night trying my best not to fall to the floor from the middle section at my butt where it sagged horribly. In the morning we were ready to call the boat basin to have a new mattress for each of us delivered, but decided against it when we figured out that turning the mattresses over made the situation tolerable. Coupled with just how narrow these boats are for getting around and being comfortable, it was not an auspicious beginning.

Needless to say, the first night was a miserable sleep for both Kap and I. Our single beds were on opposite sides of our tiny stateroom (if you can call it that, and it was also the hallway between Tom and Linda’s stateroom and the rest of the boat). Our mattresses were broken-down affairs, and I spent most of the night trying my best not to fall to the floor from the middle section at my butt where it sagged horribly. In the morning we were ready to call the boat basin to have a new mattress for each of us delivered, but decided against it when we figured out that turning the mattresses over made the situation tolerable. Coupled with just how narrow these boats are for getting around and being comfortable, it was not an auspicious beginning.

Tom and Linda didn’t fare much better, as a hot water bottle that Linda took to bed to sooth an aching neck pain leaked, soaking their bed and duvet. It reminded me of the Pink Panther scene where Inspector Clouseau popped the cork on a champagne bottle in bed and under the blankets.

In the morning, an instant latte (nothing like Starbucks, and it would be a full two weeks before we’d see our next Starbucks), some toast and marmalade, and the camaraderie between the four of us made it all better.

In the morning, an instant latte (nothing like Starbucks, and it would be a full two weeks before we’d see our next Starbucks), some toast and marmalade, and the camaraderie between the four of us made it all better.

Sunday, September 21, 2014, Marbury to Whitchurch. Today was declared to be Tom’s day as boat Captain – which ostensibly gave him the authority to choose when we’d stop for the day (although, it really was a 4-way decision) . . . and of course, he got to drive.

Knowing that we were on an out-and-return trip that can be done in a week – and we had a full two weeks to do it in – we were not in any hurry to get anywhere. The distance traveled was barely eight miles, but it had our biggest concentration of locks on the entire route – a total of 10 locks, three of which were stair step locks as we rounded the sweeping curve to Grindley Brook on the north side of Whitchurch.

Drive on the left, drive on the right – which will it be? Remember, this is the U.K., where cars have right hand drive and the lane you drive in is on the left. So, on a canal narrowboat, where you stand at the rear and steer with a tiller/rudder in the center of the boat, which side of the canal do you drive on, and which side do you pass an oncoming boat?

Well, it was surprisingly (at least to us). U.K. canals are more narrow than anywhere on the Continent, and oftentimes there are weeds growing from the bank and out into the canal – in some places a surprising amount. Further, the canals shallow up along the sides – often to less than 18”, which is a narrowboat draft – so it’s advisable to steer as much as possible in the center of the canal. It also gives a slight advantage to the driver on approach to a corner, as they are typically blind due to the high growth along the bank, and even though we were only traveling at 2-3 MPH, you really have to keep in mind that the bow is 66’ in front of you, and it takes quite a long time to change its direction of travel.

So, which side do you pass on? Well, the protocol is to pass port to port (i.e., on the right) . . . or opposite what you do on a British highway or street. Go figure.

In the photo at left, you can see that Tom is driving right down the middle as he approaches the oncoming narrowboat – and so is the driver of that oncoming boat. More importantly, with uncut weeds/shrubs growing out from both sides of the canal, the waterway has narrowed down considerably, to the point where one or both boats will have to hug the canal side to safely pass. Etiquette is also to slow down when meeting boats, and it’s typical that a pleasant exchange, nod of the head, and a small wave between drivers and passengers is done – all very British, all very polite, and all very friendly.

In the photo at left, you can see that Tom is driving right down the middle as he approaches the oncoming narrowboat – and so is the driver of that oncoming boat. More importantly, with uncut weeds/shrubs growing out from both sides of the canal, the waterway has narrowed down considerably, to the point where one or both boats will have to hug the canal side to safely pass. Etiquette is also to slow down when meeting boats, and it’s typical that a pleasant exchange, nod of the head, and a small wave between drivers and passengers is done – all very British, all very polite, and all very friendly.

Transiting tunnels. Along the way we transited six tunnels in each direction, some as short as 50’, and the longest being ¼ mile long. Invariably, one entrance or the other was at a sharp bend in the canal, making the entrance almost blind. Not long after we got started, we decided it would be a good idea to have at least one person at the bow at all times, giving an extra 66’ notice to the narrowboat driver that something significant was ahead – another narrowboat coming around a steep canal bend, or a hidden bridge or tunnel at a curve.

In photo #1 of the tunnel sequence, Kap is letting Tom know that a hidden tunnel at the beginning of the Grindley Bridge Locks is fast approaching. By this time, the boat had better be at dead slow, or it will be impossible to negotiate the sharp curve.

In photo #1 of the tunnel sequence, Kap is letting Tom know that a hidden tunnel at the beginning of the Grindley Bridge Locks is fast approaching. By this time, the boat had better be at dead slow, or it will be impossible to negotiate the sharp curve.

In photo #2, the curve has been made, but now the task is to get the narrowboat perfectly lined up for the bow to make the tunnel entrance – where there is a scant 6-8” of clearance with the stone side rails. The tunnel width is deceiving, as it has the original towpath just off Kap’s right side, so gauging the clearance requires the driver to lean out in both directions to line up.

In photo #2, the curve has been made, but now the task is to get the narrowboat perfectly lined up for the bow to make the tunnel entrance – where there is a scant 6-8” of clearance with the stone side rails. The tunnel width is deceiving, as it has the original towpath just off Kap’s right side, so gauging the clearance requires the driver to lean out in both directions to line up.

Once inside the tunnel (photo #3), it actually becomes easier, as the boat has nowhere else to go but through the tunnel, often gently brushing the tunnel side rails to keep it going straight.

Once inside the tunnel (photo #3), it actually becomes easier, as the boat has nowhere else to go but through the tunnel, often gently brushing the tunnel side rails to keep it going straight.

It’s hard to see in photo #3, but there is a cream-colored Mercedes sedan directly ahead of the boat’s bow, and that’s a good indication the canal makes a sharp jog to the left immediately after exiting the tunnel. All of these telltale signs have to be carefully watched by the driver; otherwise things catch up with you and before you know it, you’ve banged hard into something.

Stair step locks. Most canal locks are single, providing for an elevation change of up to 7’ in a single lock. On the U.K. canal system, single locks are “self-service”, meaning that each boat’s crew works all of the lock mechanisms, while the boat driver remains on board the boat to drive it through. For elevation changes greater than 7’ (or so), a staircase lock is typically built, and because they are significantly more complex, a lockkeeper is on duty to oversee the lock operation. The complexity is due to these factors: (1) multiple boats may be in the various step locks at one time, and management of this is critical; and (2) efficient water usage must be maintained, as the water valves and lock doors for the various step locks must be opened/closed in proper sequence for lock operation to work. Even with a lockkeeper, it’s fairly complex if really good spatial ability isn’t maintained (I typically relied on the lockkeeper to tell me what to do, rather than do stupid things on my own).

In the photo at left, we’ve entered the lower chamber of the stair step Grindley Locks (i.e., we’re being “stepped up” to a higher canal level, and the chamber we’ve just entered is drained (except for enough water to float us). Kap is running up the side steps, windlass crank in hand, to assist with opening the water valve above so that our lock chamber can be filled. There is a boat in the lock chamber directly in front of us – you can just see the boat’s driver above the doors at the head of our lock. As soon as that boat exits his lock and the lock doors close behind him, Kap (on one side), and the lockkeeper (on the other side) will crank the water valves on the lock doors open, flooding our lock and floating us up to the level where you now see the boat in front of us.

In the photo at left, we’ve entered the lower chamber of the stair step Grindley Locks (i.e., we’re being “stepped up” to a higher canal level, and the chamber we’ve just entered is drained (except for enough water to float us). Kap is running up the side steps, windlass crank in hand, to assist with opening the water valve above so that our lock chamber can be filled. There is a boat in the lock chamber directly in front of us – you can just see the boat’s driver above the doors at the head of our lock. As soon as that boat exits his lock and the lock doors close behind him, Kap (on one side), and the lockkeeper (on the other side) will crank the water valves on the lock doors open, flooding our lock and floating us up to the level where you now see the boat in front of us.

Visiting Whitchurch. Whitchurch is one of the two largest towns we’d pass through on this cruise (population around 8,000), so we wanted to explore it a bit, as well as have dinner. It’s another of the towns in the area founded by the Romans – around 52AD

Visiting Whitchurch. Whitchurch is one of the two largest towns we’d pass through on this cruise (population around 8,000), so we wanted to explore it a bit, as well as have dinner. It’s another of the towns in the area founded by the Romans – around 52AD

Unfortunately, the canal builders originally planned to bypass Whitchurch altogether, and even though those plans changed, it’s a fairly long walk to the town center. After walking for what seemed an eternity, we stopped in a small grocery store to get advice on a good pub for dinner, completely forgetting the day was Sunday, and our choices were going to be slim. Turns out, the further walk to the recommended Black Bear Pub (pictured above) was another mile, and lucky for us, a guy in the checkout line who overheard our conversation stopped to pick us up with his Land Rover. As usual, the menu included steak and ale pie, a chicken fillet in a curry sauce, a ham steak (called Gammon Steak in the U.K.), a fish dish of smoked haddock and prawns, the standard lamb dish, and a roast duck leg (none of which I was hungry for, so I settled for a Black Bear steak burger). I was also getting my quota of Guinness beer pints (if it wasn’t for Guinness, I wouldn’t drink beer, as it’s silky smooth, without the bitterness of other beers).

Given the distance we’d walked to get here, we planned to call a taxi, but that idea was nixed when we learned there are no taxis working on Sunday. In the dark, we walked a very long way back to the boat.

Monday, September 22, 2014, Whitchurch to Ellesmere. Today was our longest day so far, cruising slowly (never more than 2-3 knots), covering mile after mile, pressing on to arrive at Ellesmere just after 5PM. Had we chosen to, we could have stopped for the night at any spot along the route, but we wanted to spend a night at Ellesmere in any case, so a long day made sense. Unfortunately, the narrowboat hire basin we planned to stop at for a fresh water refill and black water pump-out was closed for the evening and wouldn’t be open the next day due to a power problem.

England-Wales border. By a quirk of geography (a pronounced bulge in the Wales border along our route), as well as the squiggly nature of the canal, we crossed the Welsh/English border multiple times on our cruise. Since both countries are part of the United Kingdom, though, the crossings were barely noticeable – in fact, just a small 4’ high milepost type of marker in one spot. For some reason that we could not explain, though, at the junction of the Llangollen Canal with the Shropshire Union Prees Branch canal was a prim and proper Customs House (shown in the photo at left). It almost certainly doesn’t serve as a border crossing house at this point, but there was no indication what it’s now used for – possibly a private residence.

England-Wales border. By a quirk of geography (a pronounced bulge in the Wales border along our route), as well as the squiggly nature of the canal, we crossed the Welsh/English border multiple times on our cruise. Since both countries are part of the United Kingdom, though, the crossings were barely noticeable – in fact, just a small 4’ high milepost type of marker in one spot. For some reason that we could not explain, though, at the junction of the Llangollen Canal with the Shropshire Union Prees Branch canal was a prim and proper Customs House (shown in the photo at left). It almost certainly doesn’t serve as a border crossing house at this point, but there was no indication what it’s now used for – possibly a private residence.

Along this part of the route, Linda took the opportunity to try her hand at driving the boat. Truth be told, it isn’t an easy boat to drive, as the rudder is bent, the tiller handle is also bent and doesn’t fit the shaft down to the rudder very well – with the result that the boat doesn’t track very well (this is a polite way to say, don’t look away for even a moment or the boat will be going in a direction you don’t want. After this experience, Linda wasn’t very excited about driving again.

Along this part of the route, Linda took the opportunity to try her hand at driving the boat. Truth be told, it isn’t an easy boat to drive, as the rudder is bent, the tiller handle is also bent and doesn’t fit the shaft down to the rudder very well – with the result that the boat doesn’t track very well (this is a polite way to say, don’t look away for even a moment or the boat will be going in a direction you don’t want. After this experience, Linda wasn’t very excited about driving again.

!

!

The terrain through this section, though, was interesting. It was very remote and most of the time the surrounding land was lower than the canal elevation. There were no signs of habitation whatsoever, although there were lots and lots of black and white cows scattered about – and you find yourself in the middle of “the Whixall Moss” … which in fact, is a peat bog that formerly provided commercial peat for gardens. But now it’s been turned into a nature preserve that’s popular with birders. I called the area the Grimpin Mire, as it looks exactly like the bog of that name in the Sherlock Holmes story, Hound of the Baskervilles (although that was set in Scotland – and it was full of quicksand and all sorts of unsavory characters that made it sinister).

The terrain through this section, though, was interesting. It was very remote and most of the time the surrounding land was lower than the canal elevation. There were no signs of habitation whatsoever, although there were lots and lots of black and white cows scattered about – and you find yourself in the middle of “the Whixall Moss” … which in fact, is a peat bog that formerly provided commercial peat for gardens. But now it’s been turned into a nature preserve that’s popular with birders. I called the area the Grimpin Mire, as it looks exactly like the bog of that name in the Sherlock Holmes story, Hound of the Baskervilles (although that was set in Scotland – and it was full of quicksand and all sorts of unsavory characters that made it sinister).

On our arrival in Ellesmere we found most of the moorage spots in the area already taken. This isn’t a good thing, as turnaround possibilities with a 66’ narrowboat are very limited – so it’s important that you take the first available place you come to. Recognizing this, we opted for the end of the moorage queue along the banks outside of town (photo below, with Tom and Kap discussing the day’s events on the stern deck, such as it is). We knew it would again be another long walk to dinner.

When it was time to walk into town we met an old gentlemen on the pathway with a cane, who we took to be a local out for a walk, and asked him for a pub/restaurant recommendation. He instantly came back with The Black Lion Hotel (are you seeing a pattern in pub names???), and then said he’d see us there shortly. If the place was good, we decided to “shout him a pint” (as the Brits, Kiwis, and Aussies say when you buy someone a round). It was good, but by now we could almost cite pub menus by heart.

When it was time to walk into town we met an old gentlemen on the pathway with a cane, who we took to be a local out for a walk, and asked him for a pub/restaurant recommendation. He instantly came back with The Black Lion Hotel (are you seeing a pattern in pub names???), and then said he’d see us there shortly. If the place was good, we decided to “shout him a pint” (as the Brits, Kiwis, and Aussies say when you buy someone a round). It was good, but by now we could almost cite pub menus by heart.

Tuesday, September 23, 2014, Ellesmere to Jack Mytton Inn. After a quick breakfast on the boat we headed for town to explore the large Tesco supermarket at the head of the canal stub (the stub was about 1,500’ long, and narrowboats were moored in every available spot). Tuesday is market day in Ellesmere, held in the large town hall in the center of town. It was part farmer’s market and part flea market – and we purchased two steak and ale and two pork and ale pies to take back to the boat (for the freezer, and a rainy day if we decided to stay on board for dinner). These are like a chicken pot pie, with a flaky crust encasing a meat and gravy center.

We then walked around the small town center, chancing upon a bakery that had several kinds of marinated olives (for all of us at Happy Hour except Kap). Although it was already mid-morning, we took the opportunity to indulge in an excellent latte at a sidewalk table and watched the world go by for a while. To our surprise, we learned the bakery opens at 7:30AM with the latte service, which we vowed to take advantage of on our return cruise, rather than the instant powder stuff we were drinking on the boat.

We didn’t strike out on the day’s cruise until after noon, deciding that it was to be a short day, and only 5½ miles distance. The task for the day was the Jack Mytton Inn, a highly popular pub in the extremely tiny village of Hindford (population maybe 10) that I’ll explain about in a bit.

The scenery. So far, I think I’ve photographed almost every overhead bridge we’ve come to – as each seems more scenic than the last. The one in the photo at left is numbered 11W (on the oval plate above the center of the bridge arch, with the W meaning we’re in Wales), and with so many bridges to go through this gave us quick knowledge of exactly where we are at all times.

The scenery. So far, I think I’ve photographed almost every overhead bridge we’ve come to – as each seems more scenic than the last. The one in the photo at left is numbered 11W (on the oval plate above the center of the bridge arch, with the W meaning we’re in Wales), and with so many bridges to go through this gave us quick knowledge of exactly where we are at all times.

None of us had noticed it before, but Tom became curious why every bridge and lock has a large stone/brick box nearby – a box that was obviously built to last for a very long time (there’s one in the photo, at the extreme left, just before the bridge). After a close-up inspection we learned that each box has a half dozen very long 6×12 planks stacked in it, and we then noticed that the canal bank near it has a slot on each side of the bank to drop the boards into. Stacking the boards on edge, on top of each other, is an easy and effective way to dam up the canal, which makes lots of sense whenever there’s a breach in the canal wall. In three hundred years of operation, the canal engineers figured out how to handle all eventualities.

One of the best parts of canal scenery is the sun lighting through the trees, as well as reflections on the still water. It was at every turn, and made doubly nice on the frequent stretches where the canal traffic was so light that the water was like glass ahead of us. This is one of the benefits of cruising in this time of year, rather than July/August when the canals must be thick with boats churning up the water.

One of the best parts of canal scenery is the sun lighting through the trees, as well as reflections on the still water. It was at every turn, and made doubly nice on the frequent stretches where the canal traffic was so light that the water was like glass ahead of us. This is one of the benefits of cruising in this time of year, rather than July/August when the canals must be thick with boats churning up the water.

John “Mad Jack” Mytton. Lots of words can be used to describe this guy from 200 years ago (born 1796; died 1834): scurrilous, scandalous, outrageous, coarse, ribald, scabrous, eccentric, crazy, scalawag . . . you name it. Born into an illustrious (and very rich) family with a lineage over 500 years, and an annual income that would be worth $1M today, he broke almost every social rule in the books: riding a bear through the living room of his country estate (as the print above illustrates), setting his shirt afire to cure a bout of hiccups, taking 2,000 bottles of port to sustain him when he was sent to university at Cambridge (and continued to drink eight bottles of port a day in later life), paying voters £10 to vote for him when he stood for Parliament (and spending over $1M at today’s rate), attempting to jump a fence with a horse-drawn carriage (and failed), hunting naked even in snow storms, kept 2,000 dogs and 60 wildly decorated cats. He so loved his horse, Baronet, that he was allowed to roam the house and slept beside Jack in front of the drawing room fireplace. In the end, Mad Jack’s antics cost him his fortune, and he found himself locked up in debtor’s prison, where he died a broken man just 38 years old.

John “Mad Jack” Mytton. Lots of words can be used to describe this guy from 200 years ago (born 1796; died 1834): scurrilous, scandalous, outrageous, coarse, ribald, scabrous, eccentric, crazy, scalawag . . . you name it. Born into an illustrious (and very rich) family with a lineage over 500 years, and an annual income that would be worth $1M today, he broke almost every social rule in the books: riding a bear through the living room of his country estate (as the print above illustrates), setting his shirt afire to cure a bout of hiccups, taking 2,000 bottles of port to sustain him when he was sent to university at Cambridge (and continued to drink eight bottles of port a day in later life), paying voters £10 to vote for him when he stood for Parliament (and spending over $1M at today’s rate), attempting to jump a fence with a horse-drawn carriage (and failed), hunting naked even in snow storms, kept 2,000 dogs and 60 wildly decorated cats. He so loved his horse, Baronet, that he was allowed to roam the house and slept beside Jack in front of the drawing room fireplace. In the end, Mad Jack’s antics cost him his fortune, and he found himself locked up in debtor’s prison, where he died a broken man just 38 years old.

Why am I telling about this? Well, a local resident in Hindford runs a wonderful pub named the Jack Mytton Inn in honor of Hindford’s most famous former resident. The place had been highly recommended to us before we departed Wrenbury, so we decided this was our stop for the night. It was a Tuesday night, so we got by without a reservation, but on busy weekend nights this isn’t possible – the place is very popular with locals and narrowboat cruisers as well.

Nothing special about the menu – most of the typical pub favorites, but a couple of new ones that we decided to try. Linda had a lamb dish called “Local Welsh Lamb Henry”, slow cooked in a rich red wine and rosemary gravy, and served on mashed potatoes, with vegetables on the side. Tom and I both tried the rack of lamb, which was a bit more “pongy” than I like, but still good. Dessert was really … really! … good – a sticky toffee pudding. Almost every night after this, we tried each pub’s offering of this, to see which one might win the award for the best – but in the end, the Jack Mytton Inn version won.

Wednesday, September 24, 2014, Jack Mytton Inn to Chirk. Another day of only 5½ miles, but even though we slowly meandered along, it was a fairly short day with only one lock to pass through, one aqueduct of 710’ to cross, and the longest tunnel of the entire trip (the Chirk Tunnel, at 1,380’, or just over ¼ mile long). It was my day to drive almost all of it, including the tunnel at the very end of the day. We moored for the night just 100 yards from the west end of the tunnel mouth.

Most of the cruising day was the typical scenery – stuff that I’d already photographed several times before (and besides, I had my hands full with the tiller), so little to report . . . until we got to the Chirk Tunnel. I was finishing up a long day of driving, when suddenly there was the typical 90° bend in the canal, and shazam!, here was the mouth of a tunnel that seemed to stretch to infinity when I got lined up with the opening.

It was my first-ever tunnel, and for everyone else it was by far the longest (previously, the longest was maybe 50’). Once inside it, there was no light whatsoever around us, save for a little glow circle at the bow of the boat from the headlight. There was a very faint light ahead that was obviously the tunnel exit I was aiming for, and within a few yards into the tunnel, another faint semi-circle of light behind me. Other than that, I was steering blind.

It was my first-ever tunnel, and for everyone else it was by far the longest (previously, the longest was maybe 50’). Once inside it, there was no light whatsoever around us, save for a little glow circle at the bow of the boat from the headlight. There was a very faint light ahead that was obviously the tunnel exit I was aiming for, and within a few yards into the tunnel, another faint semi-circle of light behind me. Other than that, I was steering blind.

In the bottom photo, there’s light on the wall only because of my camera flash, which also seems to have snuffed out the “light at the end of the tunnel” and shows up here as a very faint dot just above the center bits on the boat roof.

In the bottom photo, there’s light on the wall only because of my camera flash, which also seems to have snuffed out the “light at the end of the tunnel” and shows up here as a very faint dot just above the center bits on the boat roof.

Now for the really scary part. Not long after entering the tunnel, our boat seemed to mysteriously slow down. I looked and looked at the barely visible pathway railing behind me, and sure enough it seemed like we were barely moving. I moved the throttle forward, then moved it again, and again, until I was running at top revs on the engine. It still seemed like we were barely moving, and worse, the other narrowboat that came in a couple hundred feet behind us seemed to be steadily gaining. What the hell was going on?

The boat also seemed unsteerable, and I could tell from the angle difference of the bow to the faint light ahead that we were indeed veering from side to side (and I was moving the tiller in wide sweeps, which was unusual). Could grinding the side of the boat against the tunnel rail at the water level be causing all this? I was totally mystified.

With the speed seriously reduced, it took us forever to reach the end of the tunnel, but finally we did. Once outside the tunnel I could readily see that our speed was badly diminished, but nothing made sense. Then we passed a privately-owned narrowboat waiting to enter after the tunnel was clear, and the wizened guy at the tiller hollered over to me, “Put it in reverse, then rev the engine up!” What he said didn’t make any sense, but I did what he told me. “You may have to do it multiple times,” he hollered again.

Finally, it made sense. At some point, our prop had built up a thick bunch of leaves from the fall leaves dropping in the water, and it had made our prop almost totally ineffective. Had I realized that while we were in the tunnel, we might have passed through in half the time. Live and learn.

We planned to spend the night at Chirk, and the street leading to the town center was at a high bridge crossing just a couple hundred yards outside the tunnel that we just came through. With very little room to spare, I pulled to the side and Kap and Tom got us moored for the night. Directly ahead of us (by just a meter from our bow), though, was the skankiest boat we’d seen so far on the canal – obviously derelict, but who knows if there really was someone living on it. Kap didn’t want to be moored anywhere near it, but I felt it was just an abandoned boat. (That night, Linda wrote in her daily cruise e-mail to family and friends, “I was reading The Times and there was an article about a Latvian man who is wanted in the disappearance of a young girl from the towpath. I think that the scow is his hiding hole and he comes out to prey on the unsuspecting. I can’t be sure but maybe. There could be a novel in this.” While it was said jokingly, her comments definitely left an impact with us, and we didn’t look at the scow in the same way. (Near the end of our cruise, the young woman’s body was found, and a day later, the Latvian who is the prime suspect was also found dead. This tragic incident occurred in the River Brent, which is in northern London.)

We planned to spend the night at Chirk, and the street leading to the town center was at a high bridge crossing just a couple hundred yards outside the tunnel that we just came through. With very little room to spare, I pulled to the side and Kap and Tom got us moored for the night. Directly ahead of us (by just a meter from our bow), though, was the skankiest boat we’d seen so far on the canal – obviously derelict, but who knows if there really was someone living on it. Kap didn’t want to be moored anywhere near it, but I felt it was just an abandoned boat. (That night, Linda wrote in her daily cruise e-mail to family and friends, “I was reading The Times and there was an article about a Latvian man who is wanted in the disappearance of a young girl from the towpath. I think that the scow is his hiding hole and he comes out to prey on the unsuspecting. I can’t be sure but maybe. There could be a novel in this.” While it was said jokingly, her comments definitely left an impact with us, and we didn’t look at the scow in the same way. (Near the end of our cruise, the young woman’s body was found, and a day later, the Latvian who is the prime suspect was also found dead. This tragic incident occurred in the River Brent, which is in northern London.)

After tying up, we walked to Chirk. Less than a block from where we started, we all smelled the unmistakable aroma of cocoa – and a glance to the left brought out a large factory complex that is the Cadbury cocoa plant. It was really surprising that what we smelled was so like the finished product. (When we got to the factory’s entrance gates a block further, the corporate name of the factory was Mondelēz International, which none of us had ever heard of – in fact, we thought it was some European company. Turns out, Cadbury was bought in a hostile takeover in 2009 by Kraft Foods (which all of us somehow missed or forgot), and a later split of Kraft Foods into two parts created this company.) It’s sad when an almost 200 year old national icon is picked up by a corporate raider, but in reading about it, I learned that the shareholders made out very well.)

After tying up, we walked to Chirk. Less than a block from where we started, we all smelled the unmistakable aroma of cocoa – and a glance to the left brought out a large factory complex that is the Cadbury cocoa plant. It was really surprising that what we smelled was so like the finished product. (When we got to the factory’s entrance gates a block further, the corporate name of the factory was Mondelēz International, which none of us had ever heard of – in fact, we thought it was some European company. Turns out, Cadbury was bought in a hostile takeover in 2009 by Kraft Foods (which all of us somehow missed or forgot), and a later split of Kraft Foods into two parts created this company.) It’s sad when an almost 200 year old national icon is picked up by a corporate raider, but in reading about it, I learned that the shareholders made out very well.)

Once in town, we headed first to a chemist (pharmacy or drug store in our terms), as Kap had come down with a nasty cold and needed some meds to hopefully bring it under control. To find the chemist, we stopped in a small bakery to ask directions. Without thinking, I asked for directions to the “city center” . . . and the surprised young woman behind the counter stammered, “This is a very small village . . . this is the city center!” Oops – I pulled a gaff, by not having a clue about the size of Chirk before opening my mouth.

Once in town, we headed first to a chemist (pharmacy or drug store in our terms), as Kap had come down with a nasty cold and needed some meds to hopefully bring it under control. To find the chemist, we stopped in a small bakery to ask directions. Without thinking, I asked for directions to the “city center” . . . and the surprised young woman behind the counter stammered, “This is a very small village . . . this is the city center!” Oops – I pulled a gaff, by not having a clue about the size of Chirk before opening my mouth.

As the afternoon was getting on, we decided to get a look at the famous Chirk Castle, built in 1295 as part of the string of castles that defended the north of Wales. Our map indicated it’s on the outskirts of town and across the canal that we had just come from. We headed that direction, but it was soon obvious it was a 2-mile walk to the castle grounds, and then a 2-mile walk back. None of us were keen on that, so we called for a taxi to drive us there, wait for us at the castle door while we looked around, then bring us back to the city. It was a bit pricey, but certainly saved our legs.

As the afternoon was getting on, we decided to get a look at the famous Chirk Castle, built in 1295 as part of the string of castles that defended the north of Wales. Our map indicated it’s on the outskirts of town and across the canal that we had just come from. We headed that direction, but it was soon obvious it was a 2-mile walk to the castle grounds, and then a 2-mile walk back. None of us were keen on that, so we called for a taxi to drive us there, wait for us at the castle door while we looked around, then bring us back to the city. It was a bit pricey, but certainly saved our legs.

Like every night before, our only choice for dinner was the town’s pub, at The Hand Hotel. The menu was pretty much the same as all other pubs we’d eaten at in the recent past . . . with one exception – for a starter we each had a Welsh rarebit in honor of our first real meal in Wales (also spelled and pronounced as Welsh rabbit, which I originally thought contained rabbit meat). It’s traditionally a dish of doctored-up and melted cheddar cheese, poured over hunks of toasted bread. It was quite yummy.

Like every night before, our only choice for dinner was the town’s pub, at The Hand Hotel. The menu was pretty much the same as all other pubs we’d eaten at in the recent past . . . with one exception – for a starter we each had a Welsh rarebit in honor of our first real meal in Wales (also spelled and pronounced as Welsh rabbit, which I originally thought contained rabbit meat). It’s traditionally a dish of doctored-up and melted cheddar cheese, poured over hunks of toasted bread. It was quite yummy.

Interestingly, I’ve eaten Welsh rarebit a number of times and even have a recipe for it in my recipe files. I first learned of it on one of my teaching visits to Springfield, IL – where I often taught classes back in the 1980s for IT professionals working at the State of Illinois computer center. A Springfield restaurant had a specialty of rarebit, but their twist on it was to serve it over French fries, and it too was quite good, even though it wasn’t the real thing.

Thursday, September 25, 2014, Chirk to Llangollen. Today’s cruise is 8 miles, but they will undoubtedly be the most interesting 8 miles of the entire trip. It’s Tom’s day to drive (although we had dispensed with the idea of one person driving the entire day, as it proved too tiring). Kap and I would be in the bow “spotting” for Tom, and Linda would be at the stern to help keep track of exactly where we were and what was coming up next.

Our first major event of the day was the Whitehouse Tunnel, the shorter cousin to the Chirk Tunnel we passed through yesterday afternoon – at only 565’, or less than half the length. The photo at left isn’t a black-as-night blank photo, but rather, a photo taken from the bow of our narrowboat as we entered the Whitehouse Tunnel (and you’ll almost certainly have to click on the photo to enlarge it to see the “light at the end of the tunnel”. As usual, there’s a sharp turn at the end, and that’s another narrowboat making the turn that you can barely see in the murky dark ahead. As Linda put it in her e-mail home, “Entering a tunnel or bridge is like threading a needle 60’ ahead of you. You are moving the 6½’ bow into an 8′ opening and it seems that the approach is almost always angled. We are going up stream and the current can move your bow as it comes through the narrow opening.” All definitely true.

Our first major event of the day was the Whitehouse Tunnel, the shorter cousin to the Chirk Tunnel we passed through yesterday afternoon – at only 565’, or less than half the length. The photo at left isn’t a black-as-night blank photo, but rather, a photo taken from the bow of our narrowboat as we entered the Whitehouse Tunnel (and you’ll almost certainly have to click on the photo to enlarge it to see the “light at the end of the tunnel”. As usual, there’s a sharp turn at the end, and that’s another narrowboat making the turn that you can barely see in the murky dark ahead. As Linda put it in her e-mail home, “Entering a tunnel or bridge is like threading a needle 60’ ahead of you. You are moving the 6½’ bow into an 8′ opening and it seems that the approach is almost always angled. We are going up stream and the current can move your bow as it comes through the narrow opening.” All definitely true.

What does a “sticky wicket” look like? Everyone knows the term, but how many know what it actually means. Well, it’s “a difficult circumstance” – and originates from the game of cricket, caused by the difficulty in batting caused by a pitch on damp and soft ground. You could also say that the predicament Tom found himself in the photo at left is a very sticky wicket. We’re cruising right down the middle of the canal, at a point where it’s wide enough for little more than two boats. There’s a boat moored on the right, and just at the point of our meeting is another boat coming right down the middle of what’s left. The solution is to pull back the throttle, cruise to dead slow to wait until the oncoming boat passes, steer a bit to the right, then swing in just after the oncoming boat clears the moored boat. Oddly, after going for miles without meeting or seeing another boat, we’d often find ourselves in this type of sticky wicket.

What does a “sticky wicket” look like? Everyone knows the term, but how many know what it actually means. Well, it’s “a difficult circumstance” – and originates from the game of cricket, caused by the difficulty in batting caused by a pitch on damp and soft ground. You could also say that the predicament Tom found himself in the photo at left is a very sticky wicket. We’re cruising right down the middle of the canal, at a point where it’s wide enough for little more than two boats. There’s a boat moored on the right, and just at the point of our meeting is another boat coming right down the middle of what’s left. The solution is to pull back the throttle, cruise to dead slow to wait until the oncoming boat passes, steer a bit to the right, then swing in just after the oncoming boat clears the moored boat. Oddly, after going for miles without meeting or seeing another boat, we’d often find ourselves in this type of sticky wicket.