So far this summer we’ve gotten to know Roseanne Roseannadanna quite well – and Kap is threatening to rename Flying Colours to Roseannadanna! For those readers too young to have watched (or weren’t inclined to watch) the original cast of Saturday Night Live back in the 1970s, Roseanne Roseannadanna always ended her news reading with the words, “It’s always something!” Well, those are our bywords for this summer on Flying Colours . . . if it isn’t one thing it’s another. The main thing we’ve learned is, don’t let your boat sit untouched and unloved for a year and a half! (To see the lovely Roseannadanna, try the video at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xPQFQzSxxR0.)

So far this summer we’ve gotten to know Roseanne Roseannadanna quite well – and Kap is threatening to rename Flying Colours to Roseannadanna! For those readers too young to have watched (or weren’t inclined to watch) the original cast of Saturday Night Live back in the 1970s, Roseanne Roseannadanna always ended her news reading with the words, “It’s always something!” Well, those are our bywords for this summer on Flying Colours . . . if it isn’t one thing it’s another. The main thing we’ve learned is, don’t let your boat sit untouched and unloved for a year and a half! (To see the lovely Roseannadanna, try the video at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xPQFQzSxxR0.)

But, mixed with lots of things going wrong, there’s still nothing as good as being on the water. At 6AM, with good light but a mostly overcast sky, we quietly slipped out of the SYC Cortes Bay outstation on Cortes Island – close to the entrance to Desolation Sound. We were heading for slack water at Yaculta Rapids (pronounced hereabouts as “YEW-cla-ta”, which doesn’t make sense at all, as it puts the “l” in the wrong place), scheduled for 9AM. Yaculta is the first of three rapids that are closely-spaced within a total distance of a mile, with a 90° bend in the waterway around the NE corner of Stuart Island and between Sonora Island. From there we’d continue to Blind Channel Resort, where we planned to have a hamburger lunch on their deck upon arrival. We’d then stay two nights – the first to have a great dinner at the Blind Channel Resort, and the second to dinghy over to the nearby Cordero Lodge for a German schnitzel dinner the second night.

(Remember, you can click on any photo to enlarge. Also don’t forget that the formatting of this blog post is better – everything lines up better – when you can read it online at www.ronf-flyingcolours.com – click on this link to go there. Also, if you’re logged into the post with your own userid, you can request an automatic update whenever a new blog post is put up – just click on the Subscribe link and enter your e-mail address. You cannot do this, though, if you’re logged in using the “friends” username.)

Kap slightly misinterpreted the slack timings in the tide table book, so we arrived a bit early at Yaculta. She slowed to 7 knots to kill some time, but we still went through the rapids just before slack – which meant the whirlpools were stronger than we’d like. Complicating it, almost immediately after Yaculta and just at the entrance to Gilliard Passage (a half mile after Yaculta), we hit heavy ground fog. Following a 40’ (or so) trawler that was intent on going two knots slower than we cared to go, there wasn’t room to pass in the narrow passage, and even though we didn’t have the best rudder control at that speed, we were nevertheless forced to follow nose to tail.

Kap slightly misinterpreted the slack timings in the tide table book, so we arrived a bit early at Yaculta. She slowed to 7 knots to kill some time, but we still went through the rapids just before slack – which meant the whirlpools were stronger than we’d like. Complicating it, almost immediately after Yaculta and just at the entrance to Gilliard Passage (a half mile after Yaculta), we hit heavy ground fog. Following a 40’ (or so) trawler that was intent on going two knots slower than we cared to go, there wasn’t room to pass in the narrow passage, and even though we didn’t have the best rudder control at that speed, we were nevertheless forced to follow nose to tail.

Just after the third rapids, called Dent Rapids because they’re at a squeeze point where Dent Island narrows down the passage with Sonora Island, the fog had dispersed to the point where we could see a football field length in front of us and Kap kicked up the speed by 2 knots to pass the slower boat. (The photo shows the fog at this point; prior to this it was so thick we couldn’t see more than 25’ in any direction, which is particularly dangerous as the speedy little 6-pack sport fishing boats from the nearby fishing lodges race through here, seemingly oblivious to other boats that might also be in the fog.) After that, we could cruise at whatever speed we felt necessary as we passed the most dangerous part of all – at Devil’s Hole. I’ll quote from the Waggoner Cruising Guide about this – “In Devil’s Hole, violent eddies and whirlpools form between 2 hours after turn to flood and 1 hour before turn to ebb. People who have looked into Devil’s Hole vow never to run that risk again.” We hug the shoreline as close as it’s safe, to stay out of the swirling maelstrom that can be Devil’s Hole.

FYI Stuff – “Rapids” are a somewhat misleading term for anyone used to fresh water rapids, in streams and rivers that boil over a jumble of water-polished rocks, often at or above the surface. Here in coastal salt water passages, which are usually wide and deep, the term rapids is applied to just a relatively shallow area (keep in mind, the typical cruising boat draws 5-7’ beneath the keel, so it has to be at least that deep for us to get through them). Many times it’s also narrow, where the mainland or pair of islands pinch down, causing a rush of current from the tidal action.

To explain the phenomenon of rapids, I should first say a few things about tides and currents. Everyone knows (or should know) that ocean tides are the result of gravitational attraction of the sun and moon (Sir Isaac Newton . . . you know, the guy who got a headache from the apple falling from the tree, hitting him on the head and giving him the idea for gravitation . . . figured out, or at least is credited with explaining tidal action).

To explain the phenomenon of rapids, I should first say a few things about tides and currents. Everyone knows (or should know) that ocean tides are the result of gravitational attraction of the sun and moon (Sir Isaac Newton . . . you know, the guy who got a headache from the apple falling from the tree, hitting him on the head and giving him the idea for gravitation . . . figured out, or at least is credited with explaining tidal action).

Because of its relative closeness to us, the moon has considerably more tidal effect than the sun (about twice as much). It’s actually gravity and inertia that create tides, as the gravitational attraction from the moon gets the ocean water moving, and inertia keeps it moving, causing two large bulges of ocean water on opposite sides of the Earth. (the image above is from http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/education/kits/tides/media/supp_tide03.html) As shown in the graphic, on the side of the Earth nearest (facing) the moon, the moon’s gravitational force “pulls” the ocean’s waters toward it, creating one bulge; on the Earth’s far side, inertia takes over and creates the opposite bulge.

In the simplest sense, tides are very long-period waves resulting from these changing ocean bulges from the pull of the moon and sun. When the crest of the tidal wave reaches shore, it’s known as “high tide”; when the trough of the next wave cycle reaches shore it’s known as “low tide”.

Booker Lagoon, Here We Come! Thursday, 26 June, 2014, we pulled out of Blind Channel Resort at 6:10AM, with the sun rising over the mountains to the east of Blind Channel and a clear blue sky. In the photo, Couverden is still at the dock, ready to go, but departed five minutes after us. As you can also see, moorage is along a single dock, with seven finger piers at right angles, with room for a boat on either side of the finger – which means a total of 15 boats can be moored there. On the inside of the main dock is room for at least 5 more smaller boats (25’ or so) that are side-tied on the dock. A power pedestal at the head of each finger pier provides 30A or 50A shore power (we use 50A power).

Booker Lagoon, Here We Come! Thursday, 26 June, 2014, we pulled out of Blind Channel Resort at 6:10AM, with the sun rising over the mountains to the east of Blind Channel and a clear blue sky. In the photo, Couverden is still at the dock, ready to go, but departed five minutes after us. As you can also see, moorage is along a single dock, with seven finger piers at right angles, with room for a boat on either side of the finger – which means a total of 15 boats can be moored there. On the inside of the main dock is room for at least 5 more smaller boats (25’ or so) that are side-tied on the dock. A power pedestal at the head of each finger pier provides 30A or 50A shore power (we use 50A power).

On shore are the various buildings that make up the resort, including the largest part of the main building which houses the Cedar Post Restaurant. At the right end of the building is a General Store. In front of the building is a brick patio, with a half dozen picnic tables and a small cookhouse, with a nice, sunny terrace to have a noonday hamburger and a beer (which we were looking forward to on our arrival, but unfortunately, doesn’t open until July 1 when things start to get busier). There are four fairly large homes built into the background, one for each generation of the Richter family, who live here year around.

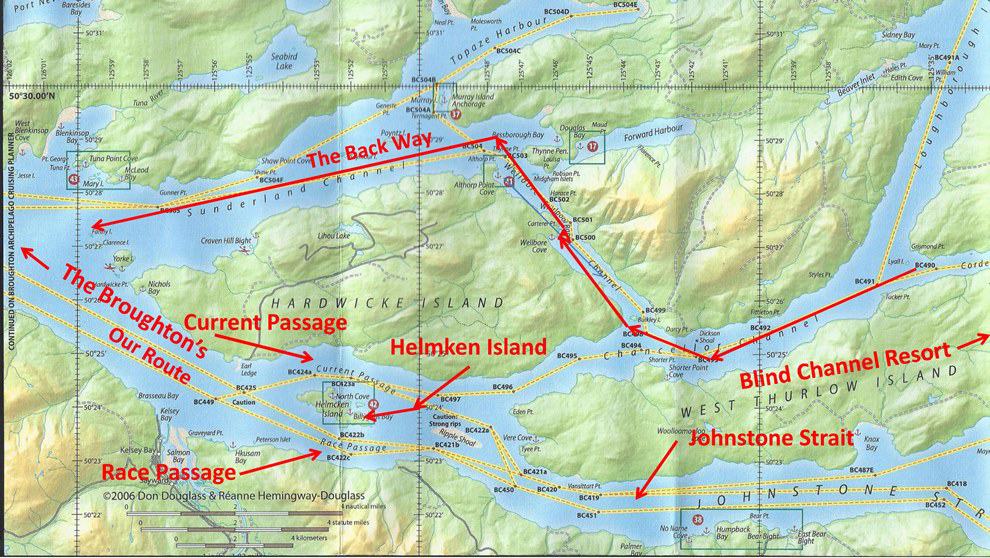

This morning, our route was west on Mayne Passage and into Johnstone Strait, with the day’s goal of reaching Booker Lagoon and hopefully, a boatload of prawns. Once in Johnstone Strait we had a small 1-2 kts “push” with the current running our direction. But that push really became good where Helmken Island splits the waterway, creating the narrow (1/4 mile wide) Current Passage on the north and Race Passage on the south, giving us a wonderful 15 kts speed “over the ground” above our 10 kts speed “through the water”. It’s always a good feeling to get a free ride like that (provided you don’t think too much about all the other times when the current is against you, taking away your speed.

This morning, our route was west on Mayne Passage and into Johnstone Strait, with the day’s goal of reaching Booker Lagoon and hopefully, a boatload of prawns. Once in Johnstone Strait we had a small 1-2 kts “push” with the current running our direction. But that push really became good where Helmken Island splits the waterway, creating the narrow (1/4 mile wide) Current Passage on the north and Race Passage on the south, giving us a wonderful 15 kts speed “over the ground” above our 10 kts speed “through the water”. It’s always a good feeling to get a free ride like that (provided you don’t think too much about all the other times when the current is against you, taking away your speed.

Lots of cruisers prefer what might be called “the back way” from Blind Channel (shown on the map) – about an equal distance, but enabling them to stay off Johnstone Strait for a dozen miles of the way to the Broughton’s. Out on Johnstone Strait, the wind is frequently channeled one way or the other, running parallel with Johnstone Strait, often at gale force speeds (defined as 35 kts and above), which in itself creates uncomfortable cruising conditions. Worse, on days when the wind is blowing the opposite direction from the waves, it’s known as “wind against waves”, and they can be murderously uncomfortable – and anyone in their right mind stays off Johnstone Strait (except for the commercial boats, who typically have to go in any type of conditions).

During the morning start-up engine checks, Couverden had found a small hydraulic leak on one stabilizer just before leaving the dock at Blind Channel. If seemed to increase as they got into Johnstone Strait. Steve tried to tighten up the fittings as they were underway, but couldn’t stop the leak, so the decision was made to center the stabilizers and turn them off. With the hydraulic pressure now at 0 PSI, the leak was stopped until they could get into port for some mechanic work.

Today, Johnstone Strait was exactly the way we like to see it – very benign, and not fighting us for every mile. A friend likes to say, “when the water is boring, it’s the best”. In the photo, all you can see are slight ripples on the surface, the winds very light, and only a few small cumulus clouds in the sky.

Today, Johnstone Strait was exactly the way we like to see it – very benign, and not fighting us for every mile. A friend likes to say, “when the water is boring, it’s the best”. In the photo, all you can see are slight ripples on the surface, the winds very light, and only a few small cumulus clouds in the sky.

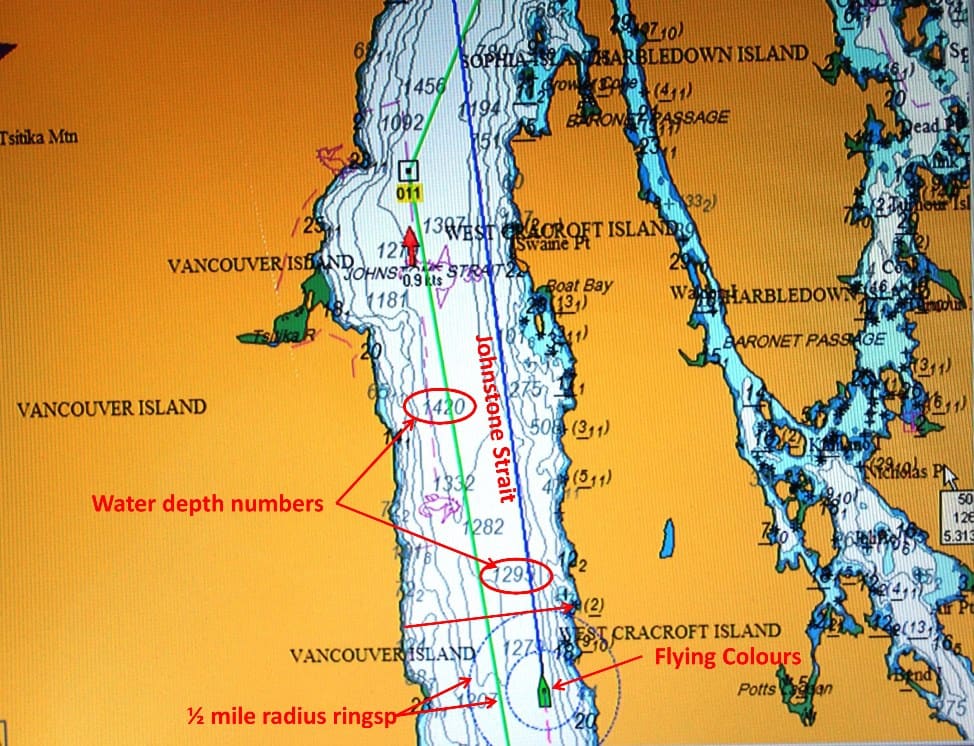

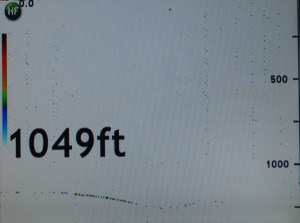

Of all the times we’ve been on Johnstone Strait, one aspect that I’d never really paid much attention to was the water depth at various places. It’s not that the information isn’t available . . . in fact, it’s shown on our electronic and paper charts, plus we always have a depth gauge screen at the dash in 2” high letters, right in front of the wheel.

What struck me this time was the ratio of depth to width of Johnstone Strait at the area where I noticed this (and snapped the accompanying photos). Flying Colours is the little green tub toy image at the bottom of the electronic navigation chart in the first photo, surrounded by two ½ mile radius rings. From these rings, you can see that the inner ring is hugging the shore of West Cracroft Island, so that means we’re cruising along ½ mile from shore. To our port side, you can eyeball it and see that we must be about 1½ miles from the shoreline of Vancouver Island, so Johnstone Strait along this stretch is a pretty constant 2 miles, or about 10,500’, wide. At the time, the depth gauge showed 1,049’ of water beneath us, and in another mile the depth would sink to around 1,299 (and a bit further from that it goes to 1,420’). Imagine that – cruising through water that’s deeper than four football fields standing on end! That’s one helluva trough carved out by glacial action in the last Ice Age!

What struck me this time was the ratio of depth to width of Johnstone Strait at the area where I noticed this (and snapped the accompanying photos). Flying Colours is the little green tub toy image at the bottom of the electronic navigation chart in the first photo, surrounded by two ½ mile radius rings. From these rings, you can see that the inner ring is hugging the shore of West Cracroft Island, so that means we’re cruising along ½ mile from shore. To our port side, you can eyeball it and see that we must be about 1½ miles from the shoreline of Vancouver Island, so Johnstone Strait along this stretch is a pretty constant 2 miles, or about 10,500’, wide. At the time, the depth gauge showed 1,049’ of water beneath us, and in another mile the depth would sink to around 1,299 (and a bit further from that it goes to 1,420’). Imagine that – cruising through water that’s deeper than four football fields standing on end! That’s one helluva trough carved out by glacial action in the last Ice Age!

Just before we turned off Johnstone Strait at Hanson Island we spotted a humpback whale surfacing and flashing his tail fluke, and at the same time we could hear the whale watching crews chatter on the radio about various sightings. This new route took us into Blackfish Sound, where the calm waters made it look like we were on a big lake. Steve and Andrea stopped to fish along the eastern shore of Hanson Island, and since we were much earlier than expected for the slack into Booker Lagoon, we cut back on the speed to 6 kts across the end of George Passage, Salmon Channel, and Howell Channel.

As we approached Booker Lagoon on the south side of Broughton Island, Kap and I had a long discussion about how to wait out the time to slack. The entrance to the lagoon is so narrow and shallow that passage through it should only be done at slack water. Our tide and current book indicated the next slack at Alert Bay (some 10 miles west of us) was scheduled for sometime between 2:30-2:50PM, and the adjustment index said that slack at Booker Lagoon would be ½ hour to an hour later than that. Outside of Booker Lagoon is a small bay, called Cullen Harbour, and being very protected from wind and waves, it’s a good place to drop the anchor to wait for slack. Once the anchor was dropped and set, we got the dinghy down and I made an exploratory run into the passage leading into the lagoon. With whirlpools that slewed me from side to side, I quickly returned and advised it was a bit too soon to go through – but how much too soon?

As we approached Booker Lagoon on the south side of Broughton Island, Kap and I had a long discussion about how to wait out the time to slack. The entrance to the lagoon is so narrow and shallow that passage through it should only be done at slack water. Our tide and current book indicated the next slack at Alert Bay (some 10 miles west of us) was scheduled for sometime between 2:30-2:50PM, and the adjustment index said that slack at Booker Lagoon would be ½ hour to an hour later than that. Outside of Booker Lagoon is a small bay, called Cullen Harbour, and being very protected from wind and waves, it’s a good place to drop the anchor to wait for slack. Once the anchor was dropped and set, we got the dinghy down and I made an exploratory run into the passage leading into the lagoon. With whirlpools that slewed me from side to side, I quickly returned and advised it was a bit too soon to go through – but how much too soon?

Soon, Andrea and Steve arrived, and with us already secured by anchor, they threw us a line and rafted to us. After back and forth discussion, we decided to go through at the recommended time – only to discover that we could have gone through quite a bit earlier. The more we do this, the more we learn that tide tables for secondary locations is a somewhat inexact science. As you can see from the accompanying photo, the passage is very narrow – the actual water part of the channel is barely 1½ boat widths wide, and maneuvering in it can be problematic – but we’ve done it enough times that (a) we don’t fear it like we used to, but (b) we respect it enough to treat it seriously.

Once inside Booker Lagoon, we decided to try something Kap and I have never done before, but which Andrea and Steve do all the time – set our initial prawn pots from the main boat on the way in, rather than having to make a separate trip out after anchoring. We’ve always worried about getting nasty prawn bait on the teak decks, as it stains and smells horrible. With me at the wheel and Kap on the back swim step setting the pots, it worked perfectly, and we now have one more “tricks of the trade” mastered.

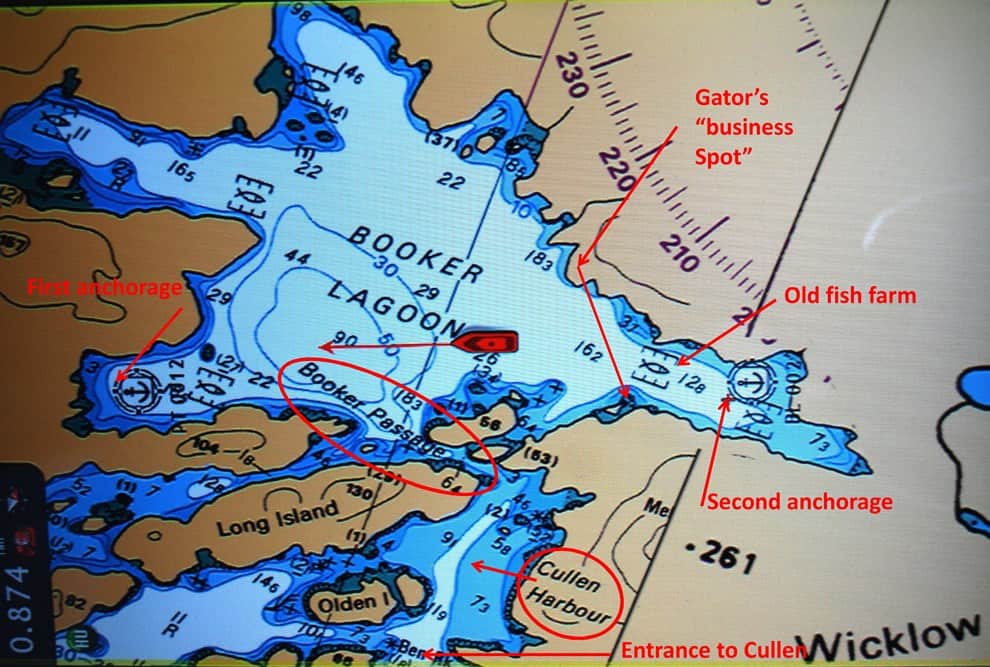

The prawn location in Booker Lagoon is near the SW corner of the lagoon, where the deepest part is – right around 300’ deep, which is the perfect depth for prawns – and with a sloping ring surrounding it that prawns like for some reason. You can see the center of the prawn spot if you scroll down to the accompanying chart photo below, at the tip of the arrow in front of the symbol for Flying Colours. The depth on the electronic chart is in meters, and measured at what is termed the “low-low tide” (this is for safety reasons, as it means a mariner doesn’t get a surprise). So the 90 that you see right next to the arrow is equal to 270’, plus another 25-30’ for tide variations, which brings us to 300’ – and that’s the deepest spot in the lagoon. Surrounding it (and at this zoom level), you see two contour lines – for 44 and 30 meters (143’ and 97’ respectively) – indicating the sloping and circular wall to the deep spot.

Kap and Steve voted for the SW bay of the lagoon to anchor (at the lower left corner in the chart photo), while Andrea and I abstained. We headed for the SW bay. We still had GPS marks on our chart plotter from an anchoring a couple of years ago, so we dropped there in 32’ of water and 100 yards from the rocky shoreline.

Andrea and Steve anchored to one side of us, and quickly settled into a Happy Hour on the foredeck of Couverden, but Kap and I still had the “snubber” attached to the anchor chain – and that produced great drama and consternation.

Before going on, I’ll explain about a snubber. Our homemade snubber (Kap made it up) is two 25′ pieces of ½” line (braided rope), each end tied to a deck cleat on either side of the bow, and in the center is a slotted stainless steel plate that’s hooked into the anchor chain. The anchor chain is then lowered in such a way that the snubber carries the weight of the chain, and not the chain extending through the bowsprit and the boat’s windlass. The reason for this is, chain going down from the boat’s bowsprit has no “give” to it, so as the boat rocks with each wave as you sit at anchor, it would put constant strain on the bowsprit, as well as the windlass. Without a snubber, the chain also makes noise throughout the night as the boat swings on it in the wind, and with your sleepy head right next to it in the V-berth, it’ll keep you awake all night. Since the snubber is line, it has a bit of stretch to it, providing the all-important “give” that makes being at anchor much more comfortable.

So, with Steve and Andrea looking on (of course, with a glass of wine in their hands), Kap and I worked on getting the snubber in place. The only problem was, there were several details of how to attach the snubber that we’d forgotten – and the details of exactly how to get it “lowered the correct way” suddenly escaped us (like it has at least two or three times in the past). For some damn reason, this is one of those situations where Kap and I don’t seem capable of discussing as reasonable people how it should be done. It probably looked and sounded like a cat fight going on on Flying Colours, but in the end we got if figured out once and for all – and as I should have done much earlier, I documented the procedure in great detail for future reference (and to help me remember it).

Kap and I settled into our first night at anchor since the middle of summer, 2012. The only problem was getting Gator ashore. At a near high tide and before the sun set we put him in the dinghy and found a rocky outcropping that he and I could scramble up while Kap held the dinghy to the rock.

In the middle of the night a storm blew in, with heavy rain, high winds, and of course, with strong current coming into the lagoon on a flood tide (meaning that we’d been at low tide, and water was now rushing into the lagoon). The big problem was, the winds were blowing right across the widest part of the lagoon, from east to west, and we took the full brunt of it at our end of the lagoon. With two miles of “fetch”, it also whipped up waves that were really buffeting us.

By daybreak it was obvious we were quite a bit closer to the rocky shore than we’d been the night before, but most of it was due to pulling out any twists and bends in the chain laying on the bottom – but ominously, it could also be from dragging the anchor due to the strong winds, waves, and current.

We needed to get Gator ashore to do his business, but it wasn’t something Kap, Gator, nor I wanted to do. In the sleeting rain, it was cold as hell. Finally at 10AM, with Kap driving the dinghy and Gator and me in the bow, we found that our previous night’s spot was no longer accessible at this tide level, so that meant finding another spot. We found what looked a workable location, but as Kap tried to maneuver us in (and I was trying to search for shallow rocks that could bite us, but the water was so murky I couldn’t see bottom), the prop on the dinghy outboard hit a rock and the immediate vibrations told us it wasn’t a good encounter. We returned to Flying Colours, explaining to Gator that he’d just have to cross his legs for a while or use the artificial turf “pup head” on the bow of Flying Colours (which he has forever refused to, but being a big boy, he bucked up very well).

We needed to get Gator ashore to do his business, but it wasn’t something Kap, Gator, nor I wanted to do. In the sleeting rain, it was cold as hell. Finally at 10AM, with Kap driving the dinghy and Gator and me in the bow, we found that our previous night’s spot was no longer accessible at this tide level, so that meant finding another spot. We found what looked a workable location, but as Kap tried to maneuver us in (and I was trying to search for shallow rocks that could bite us, but the water was so murky I couldn’t see bottom), the prop on the dinghy outboard hit a rock and the immediate vibrations told us it wasn’t a good encounter. We returned to Flying Colours, explaining to Gator that he’d just have to cross his legs for a while or use the artificial turf “pup head” on the bow of Flying Colours (which he has forever refused to, but being a big boy, he bucked up very well).

Once back on Flying Colours, Steve came by in his dinghy to discuss the situation. Concluding that if our anchor drug we’d have about 9 seconds to get the engines running and in gear – which is obviously a total impossibility – and we decided it was time to get the hell out of there.

We brought our anchor up and headed to the center of the lagoon where our prawn pots were set. Bringing them up from the main boat was unthinkable. The pots are down at 300’, our electric pot puller is on the dinghy, and even though it was now side-tied to Flying Colours, there was no way we could have the necessary two people in the dinghy plus another person hovering Flying Colours over the spot.

We brought our anchor up and headed to the center of the lagoon where our prawn pots were set. Bringing them up from the main boat was unthinkable. The pots are down at 300’, our electric pot puller is on the dinghy, and even though it was now side-tied to Flying Colours, there was no way we could have the necessary two people in the dinghy plus another person hovering Flying Colours over the spot.

Sort of killing time while we thought out our options, we motored slowly towards the finger bay at the opposite end of the lagoon (at the far right side in the chart photo above). To our surprise, the SE bay of the lagoon was almost calm (at least by comparison), much lower winds and almost no waves due to the better protection. We immediately decided this was a good place to reset our anchor, and then somehow retrieve our prawn pots. Andrea and Steve did the same. I made a test run with the dinghy to see if it could be used to take Gator to shore at a rough “beach” at this new location, but the vibration was so bad that it could only be used in an emergency. After Andrea and Steve anchored nearby, they hollered over that they’d take me and Gator to shore, and then we could head out to pull our prawn pots. The first photo above shows this sort-of-a beach at mid-tide, and even then it’s a barely reasonable rocky “beach” to go ashore – and the rocks are covered with barnacles and these cut a dog’s foot pads. The second photo shows the beach at high tide – totally disappears under water, and like most of the shoreline around Booker Lagoon, the trees grow right to the edge of the water and the branches extend out over the water at high tide, making it totally impenetrable. This is the reason we probably won’t bring the dogs again during our prawning days, when we’re likely to be at anchor quite a bit.

It’s very difficult to pull prawn pots with four people in a single dinghy, and besides, our dinghy has a pot puller, so with our dinghies side-tied together, Steve and Andrea towed us out to our pot locations. With our pot puller, we pulled all six of our pots (which were set on three lines, two pots to a line). We netted almost 300 total prawns (104 in our two pots, and upwards of 200 in their four pots).

The next plan of action was for Kap and I to hang out for the night, then catch the early morning slack and head for either Sullivan Bay Resort or Port McNeill to repair or replace the dinghy motor prop. Kap plotted both courses, and they were 19 and 21 miles, respectively. But at 2:30PM the storm suddenly lifted, the water was flat calm, no rain, no wind, and we quickly decided to pull up the anchor and head as quickly as we could for Port McNeill, as slack to exit the lagoon was at 3PM.

Crossing Salmon Passage on the way, a large pod of dolphins – maybe 10 in total, and later identified as Pacific White Sided Dolphins – were zigzagging in our bow wake (that travels down the side of the hull), with frequent leaps that took them entirely out of the water. At up to 8’ in length, and weighing as much as 400 lbs, these guys are amazingly fast, effortlessly reaching speeds of up to 25 knots (almost 30 mph) and very acrobatic. Everything they did looked like it was just for fun, and they seemed to really enjoy being alongside our boat, no more than 4’ from where I was standing in the aft cockpit of Flying Colours. We continued at 10 kts (almost 11 mph), and they were alongside for at least 30 minutes.

Crossing Salmon Passage on the way, a large pod of dolphins – maybe 10 in total, and later identified as Pacific White Sided Dolphins – were zigzagging in our bow wake (that travels down the side of the hull), with frequent leaps that took them entirely out of the water. At up to 8’ in length, and weighing as much as 400 lbs, these guys are amazingly fast, effortlessly reaching speeds of up to 25 knots (almost 30 mph) and very acrobatic. Everything they did looked like it was just for fun, and they seemed to really enjoy being alongside our boat, no more than 4’ from where I was standing in the aft cockpit of Flying Colours. We continued at 10 kts (almost 11 mph), and they were alongside for at least 30 minutes.

Their markings are a dark grey main color, with light grey flanks, light grey stripes along the sides, and a white underside. I was snapping photos as fast as I could, but when they’re underwater you can clearly see them with the naked eye, and they just look like a blur in a photo. When they leap out of the water, it’s for just a fraction of a second, and although I snapped three dozen photos, the one here is the only one that came out.

You might ask, what’s the difference between dolphins and porpoises? Well, to read about it, go to http://wonderopolis.org/home/wonder/whats-the-difference-between-dolphins-and-porpoises/. Many think dolphins and porpoises are basically the same, but there are quite a few differences, as well as quite a few similarities.

First, both dolphins and porpoises are mammals, and neither are fish, so they both have lungs (instead of gills) that breathe air. They also give birth to live young and nurse them, rather than spawning eggs.

Both dolphins and porpoises are members of the same scientific order, Cetacea, which also includes all whales (so whales are relatives of dolphins and porpoises). Dolphins and porpoises are also members of the same scientific suborder, Odontoceti, which includes all of the toothed whales. Both also “echolocate,” which means they detect objects around them using sound echoes.

The physical differences are subtle. Porpoises tend to be smaller (not longer than 7’), whereas dolphins can be 10’ in length. Dolphins are leaner and sleeker; porpoises are compact, and almost chubby in comparison. Dolphins have a more beak-like, pointed snout, and porpoises have blunt, rounded noses. The dorsal fins are different shapes between the two.

The biggest differences, though, are how they behave. Dolphins are more social with humans (and swimming alongside boats is one telltale sign), whereas porpoises are rarely seen on the surface. Dolphins got the better longevity genes, living up to 50 years or more, while porpoises only live 15-20 years. Lastly, dolphins produce sounds that humans can hear, and sounds from a porpoise are outside the hearing range of humans.

We arrived at Port McNeill just before 6PM. They were surprisingly full at the North Island Marina where we’re well known, and they found a last-minute spot for us on the fuel dock. They advised we could move to a regular moorage spot in the morning when other boats started to leave.

It had been an exceedingly long and eventful day, so after quickly getting settled in we headed up to town for dinner at the restaurant at the Haida Inn. I wolfed down a rack of baby back ribs, while Kap had a salmon filet – both were quite good, and tasted even better with a couple of glasses of wine. After taking Gator to shore for one last time, we hit the sack and were asleep the minute our heads were on the pillows.

First thing in the morning we called a marine mechanic that we’ve used before, and even though it was a Saturday he was working. We lowered the dinghy next to us on the dock and he removed the prop – bent near the tip on one blade. Our dinghy motor is a Yamaha 40hp four stroke, and the mechanic figured it was no problem finding a replacement in town. He headed off to get one, while we did some work around the boat. When he returned, though, the news wasn’t good – not a prop in town that would fit our motor, and since it was a holiday weekend (Canada Day – sort of the equivalent to our 4th of July), the earliest anyone could get one air freighted in was the following Wednesday – which would kill five days for us. Damn!

We immediately got on the phone and called Peter Schaefer in Seattle, our good friend and yacht broker who put together our purchase of Flying Colours. Peter called around, and sure enough, within the hour located a prop at a marine store in West Seattle. They were only open until 2PM on Saturday, so Peter raced there and picked up two for us (we should have had a spare on board all along). Peter then headed for Kenmore Air at the north end of Lake Washington to have them flown up to us the next day. Kenmore isn’t licensed for freight hauling into Canada, and knowing this from an experience several years earlier, we alerted Kenmore that this was an emergency situation and that gives them clearance to carry the box aboard. Sunday, shortly after noon, the props were in Port McNeill, ready to install.

Our new plan was to head out immediately to Booker Lagoon to resume prawning, but problems with Flying Colours weren’t over – a “membrane” high pressure warning on the water maker wouldn’t clear, and an hour on the phone with Brian Coverely at Delta Marine in Sidney didn’t resolve the problem – and a functioning water maker was important for a several day stay in Booker Lagoon. Nothing we tried would clear the problem, and in the end we decided we’d go without it being fixed and instead ration our fresh water use to the bone. We’d get the water maker fixed later, when we could have someone from Delta Marine fly in to fix it (and several other things).

Ahhhh, back at Booker Lagoon. Well, unfortunately it wasn’t all that easy to get back. We departed Port McNeill at 7:30AM on Monday, expecting to pull into Cullen Harbour outside of the lagoon at 10:30, just in time for the low tide slack. At 9AM, and about halfway across Blackfish Sound, we spotted a low fog bank ahead. We were hopeful it would clear by the time we got there, but that was wishful thinking. When we entered the fog, it was thick as pea soup and our visibility was less than 100’. I stayed at the helm while Kap’s eyes were glued to the radar screen and watching out the windows.

Ahhhh, back at Booker Lagoon. Well, unfortunately it wasn’t all that easy to get back. We departed Port McNeill at 7:30AM on Monday, expecting to pull into Cullen Harbour outside of the lagoon at 10:30, just in time for the low tide slack. At 9AM, and about halfway across Blackfish Sound, we spotted a low fog bank ahead. We were hopeful it would clear by the time we got there, but that was wishful thinking. When we entered the fog, it was thick as pea soup and our visibility was less than 100’. I stayed at the helm while Kap’s eyes were glued to the radar screen and watching out the windows.

Our next hope was the fog would clear before we arrived at the Booker Lagoon entrance – but again, no cigar. We could have gone into Cullen Harbour very slowly and carefully, with the electronic chart plotter zoomed in to see enough detail, but Kap didn’t feel comfortable. Instead, we idled in slow lazy circles in the channel outside, watching as the sky brightened from time to time. Each time, visibility increased to 3/8ths mile, then dropped back to 1/8th, but never enough to feel comfortable to even go into Cullen Harbour to drop anchor. Slack came and went with no clearing. Finally, at around 1PM things cleared enough to enter the outer harbor, so we ducked in and anchored. Next slack was 3PM, so once we got into the lagoon it would give us enough time to drop our prawn pots on the way past “the sweet spot”, get back to the east bay where Couverden was anchored, and get settled in for a much needed Happy Hour. (I have to say, the photo above of Couverden at anchor just after sunset, and with the water glassy smooth, could be one of my best-ever. The untouched version of the photo was almost black, but when I added a bit of Photoshop brightening the image of Couverden just sparked! It made it almost Christmas card quality.)

Now the big question was, what would the prawn catch be like? It was the Canada Day holiday weekend (that’s to Canadians as 4th of July is to Americans) – which meant there were several more boats at anchor in the lagoon – and a couple of them were in there for the same reason as us – prawning. Andrea and Steve had a really good weekend catch while we were gone, netting as many as 150-200 in a 4-pot pull. Our fears were confirmed when they came back from the Monday afternoon pot pull and reported the catch was down to 55 for those same four pots.

The next morning we spotted another Fleming enter the lagoon – turned out to be Divonasea, owned by Dick and Vona Clayton, a Canadian couple who live in Sechelt on the Sunshine Coast north of Vancouver and own a small chain of grocery stores. Then, even more surprising, another Fleming entered through the Booker Passage halfway between slack, and it was Mystic Dancer (the original Couverden from years ago), currently moored just two slips from us at Anacortes Marina, and owned by Bill and Anne Knorr of Denver. When we met up later that afternoon with Bill and his son in their dinghy during our prawn pull, Bill confided that he’d really pulled a boner by coming inside at a non-slack time, almost capsizing the boat in a strong whirlpool halfway through the passage, where the passage is at its narrowest. It could have been a real disaster if he’d run aground, possibly holed the boat, or worse, gotten it beached on the rocks in the middle of the passage – with horrible options for recovering it. (The accompanying photo shows Couverden departing Booker Lagoon, with our friends from Gig Harbor (near Tacoma), Mark and Roseanne Tilden in the background with their Selene 60’, named Koinonia.

The next morning we spotted another Fleming enter the lagoon – turned out to be Divonasea, owned by Dick and Vona Clayton, a Canadian couple who live in Sechelt on the Sunshine Coast north of Vancouver and own a small chain of grocery stores. Then, even more surprising, another Fleming entered through the Booker Passage halfway between slack, and it was Mystic Dancer (the original Couverden from years ago), currently moored just two slips from us at Anacortes Marina, and owned by Bill and Anne Knorr of Denver. When we met up later that afternoon with Bill and his son in their dinghy during our prawn pull, Bill confided that he’d really pulled a boner by coming inside at a non-slack time, almost capsizing the boat in a strong whirlpool halfway through the passage, where the passage is at its narrowest. It could have been a real disaster if he’d run aground, possibly holed the boat, or worse, gotten it beached on the rocks in the middle of the passage – with horrible options for recovering it. (The accompanying photo shows Couverden departing Booker Lagoon, with our friends from Gig Harbor (near Tacoma), Mark and Roseanne Tilden in the background with their Selene 60’, named Koinonia.

Over the next two days, our prawn catch wasn’t stupendous, but steady – 150 on Tuesday and 182 on Wednesday – which was helped by Andrea and Steve giving us their catch in one pot, as Steve had made an accurate count of their overall catch and found they were at their limit. A following day gave us 183 to add to our total, putting us within a day’s grasp of our limit of 800. The weather showed its hand, though, as a storm was forecast for the weekend, and if we didn’t make our escape from the lagoon on Friday we’d likely be stuck in there for the weekend. We decided it was time to depart after the Friday morning pot pull.

But one more incident proved to us that nothing this summer was going to be easy. Our late afternoon pot pull was in fairly high winds, whipping up waves that uncomfortably rocked us in the dinghy. We’d just pulled our pots, re-baited them for one last overnight soak, and were putting them back down. Kap was in the front of the dinghy getting clean water for the freshly-pulled prawns in a large plastic bucket. The dinghy outboard motor was running, but not in gear, as we always have it running while pulling up the pots, as it keeps the battery charged from the load of the line puller’ electric motor. As it played out, I was letting the line run through my gloved fingers to ensure there weren’t any tangles or knots in it. When the pots were about 100’ down, I noticed the wind had pushed us over the pot line running down the side of the dinghy, and for some reason I preferred it to be in full sight. Without carefully thinking through my actions, I shifted the outboard motor in forward gear to pivot us around 90°, and the moment I did so, there was a quick zzzzzzt, and the outboard motor died instantly.

I knew instantly what had just happened – the line had been near the prop, and it instantly wrapped on the prop head, jamming the prop and stalling out the motor. Not having taken in what had happened, Kap looked up and asked, “what’s happened?”

Damn! This could be really bad. Here we were in a bit of a blow, nasty waves hitting us broadside every 3-4 seconds, a seized-up outboard motor, no paddles aboard, and the last two boats in the lagoon with us had just departed on the afternoon slack. We were alone here . . . and it was emergency time!

Being the gimp that I am from last year’s knee surgery (knees working OK, but range of motion isn’t 100% of what it once was, leg strength also isn’t 100%, and knee caps are still completely numb), Kap knew immediately that the task of getting the line untangled from the prop was up to her.

We rotated the motor so that the prop was out of the water, and Kap climbed over the top of the motor cover to see if she could reach the prop. It was a real stretch, and I came back to hang on to her pant’s waist so she wouldn’t fall in during the boat rocking. The instant I did, though, water gushed in over the transom, 10 times faster (nay, 100 times faster) than our little bilge pump could pump it out, so I had to retreat to the bow to keep us afloat. Kap worked to free the line, but with the weight of the two prawn pots hanging on the prop, the first major task was to get enough slack in the line so she could pull free the untold number of line wraps that jammed the prop. Once a bit of slack was tied off, it didn’t take long to unwrap the mess, and we were free. With a bit more heavy-duty fiddling (getting the now-freed line on the correct side of the boat, for instance), the emergency was finally over – but not before we took it all in that we’d just made it through a potentially very nasty situation. It also sunk in that we’d now had two incidents with the dinghy outboard prop during our stay – how unusual is that?

(Accompanying photo – early morning light is just the greatest for on-the-water photographs, with water so calm it’s hard to tell which way is up in a photo. On the left, anchored closest to us is Couverden, a Fleming 55, and on the right in the background is the Fleming 53, Mystic Dancer.)

(Accompanying photo – early morning light is just the greatest for on-the-water photographs, with water so calm it’s hard to tell which way is up in a photo. On the left, anchored closest to us is Couverden, a Fleming 55, and on the right in the background is the Fleming 53, Mystic Dancer.)

Friday morning we pulled our pots for the last time, again not the best pull we’ve ever had, but enough to bring our total (in-the-freezer) catch to 719 from our week’s stay (well, with a 3-day detour to Port McNeill for the replacement prop). Saying farewell to Booker Lagoon, we brought up the anchor on Flying Colours and motored out of the lagoon.

The 4th of July was a good day to end our prawning adventures – but not our cruising – for 2014.

Before I end this post, let me get back on my soap box for one more FYI – having to do with farmed salmon. First, though, scroll up to the image of the electronic chart plotter showing the inside of Booker Lagoon – and note the icon inside each of the four bays that I identified as “old fish farm”. At one time, B.C. Fisheries (shame on you!) allowed a farmed Atlantic salmon fish farm to be at each of these bays, and just before we started coming here they were removed. Fish farming around here is very controversial – and it’s quite common to see bumper stickers and signs that read, “friends don’t let friends eat farmed salmon”. For some reason, Pacific salmon isn’t commercially viable in a farmed situation, but Atlantic salmon is viable (different species) – so they’ve artificially introduced a non-native salmon species into an ecosystem, creating a ton of problems. The litany of problems with farmed salmon is too long to go into here, but take a look at http://www.farmedanddangerous.org/salmon-farming-problems/ to get an idea of them. So, the next time you shop for salmon in your favorite grocery store (or see it on a restaurant menu), ask if it’s Atlantic salmon that’s been farmed on the West Coast . . . and if it is, avoid it like the plague! You’ll do the planet a favor.

Before I end this post, let me get back on my soap box for one more FYI – having to do with farmed salmon. First, though, scroll up to the image of the electronic chart plotter showing the inside of Booker Lagoon – and note the icon inside each of the four bays that I identified as “old fish farm”. At one time, B.C. Fisheries (shame on you!) allowed a farmed Atlantic salmon fish farm to be at each of these bays, and just before we started coming here they were removed. Fish farming around here is very controversial – and it’s quite common to see bumper stickers and signs that read, “friends don’t let friends eat farmed salmon”. For some reason, Pacific salmon isn’t commercially viable in a farmed situation, but Atlantic salmon is viable (different species) – so they’ve artificially introduced a non-native salmon species into an ecosystem, creating a ton of problems. The litany of problems with farmed salmon is too long to go into here, but take a look at http://www.farmedanddangerous.org/salmon-farming-problems/ to get an idea of them. So, the next time you shop for salmon in your favorite grocery store (or see it on a restaurant menu), ask if it’s Atlantic salmon that’s been farmed on the West Coast . . . and if it is, avoid it like the plague! You’ll do the planet a favor.

That’s all for now. I’ll try to have another post in a week or two.

Ron and Kap on Flying Colours